Do CVET agreements encourage employee participation in continuing vocational education and training?

Kathrin Weis

Company-based training is of significance in two regards. As well as serving as an important instrument enabling companies to cover their skill demand, it also makes a contribution towards ensuring staff employability. Participation in continuing vocational education and training (CVET) is, however, unevenly distributed. A role is also played by factors at the operational and institutional level. This article uses representative data from the BIBB Establishment Panel on Training and Competence Development (BIBB Training Panel) to investigate whether CVET agreements increase participation in such training by employees and whether this applies equally to all employee groups.

Demand for skilled employees and company-based continuing vocational education and training – the starting point

The significance of company-based training is growing as firms increasingly face skill shortages in overall terms. Both apprenticeship training and continuing vocational education and training (CVET) are important strategies for covering a company’s skill demand, especially with regard to being able to react to rapidly changing requirements and tasks. However, not all employees take part in CVET to the same extent. Employees performing unskilled tasks, which usually do not require any vocational education and training are, for example, underrepresented in CVET (cf. Nimczik 2024). This is problematic because CVET can make an important contribution to securing employability. From the company’s point of view, employees performing unskilled tasks also represent a significant potential for performing more skilled tasks in future.

CVET is also at the very top of the labour market and educational policy agenda. The aims of the “National Continuing Education Strategy” include the overall strengthening of CVET and the reduction of structural inequalities in respect of access.1 The “Work of Tomorrow Act” (full title “Act for the Promotion of Continuing Education and Training in Times of Structural Change and for the Further Development of Apprenticeship Training”)2 pursues objectives that lead in the same direction. Its goal is to maintain employability during the structural change via various measures. In terms of the funding of CVET, the “Work of Tomorrow Act” supplements the “Training Opportunities Act” by expanding support available to employees. For example, it allows higher funding rates for companies which have concluded company agreements or collective bargaining agreements containing training elements.3 The responsibility of the social partners should also be indicated in this regard.

But can relevant collective bargaining and company agreements serve as a vehicle for actually increasing employee participation in CVET, and is this true for all employee groups equally? This article places the focus of its response to these questions on collective bargaining agreements relating to CVET. It uses data from the BIBB Training Panel as a basis for providing empirical results as to whether agreements for the promotion of CVET for employees which are applicable within the scope of a collective bargaining agreement (hereinafter referred to as CVET agreements, cf. Information Box) lead to greater participation in course-based CVET by the company’s employees.

A brief overview – status of research and general institutional conditions

Empirical analyses have hitherto been limited to the correlation between the companies coverage by a collective bargaining agreement and CVET of employees. Collectively speaking, these analyses reveal a positive correspondence in that company-based CVET is more likely to take place at companies covered by a collective bargaining agreement (cf. Czepek et.al. 2015). The analyses are, however, based on data which merely indicate whether a company is covered by a collective bargaining agreement. It is unknown whether the respective collective bargaining agreement in force includes specific agreements for the promotion of CVET. As a consequence, they are unable to make any statements on the correlation between CVET agreements concluded as part of collective bargaining agreements and the employees’ participation in CVET.

The expectation would be for CVET agreements to exert a positive impact on company-funded CVET. Speaking entirely generally, agreements are the result of collective negotiations between the employees’ representatives and the employer and contain improvements. Otherwise, consent is usually not achieved and therefore no agreement is concluded (cf. Ellguth/Kohaut 2022). Within the context of the promotion of CVET, this means that CVET agreements facilitate or enhance aspects such as access to CVET for employees. Employees with lower levels of individual bargaining power, for example low-skilled employees, can especially benefit from agreements that have been collectively negotiated (cf. Wotschack/Solga 2014). Within the context of CVET, such employees also constitute the employee group which has been previously underrepresented in CVET participation. Collective bargaining agreements bring advantages for the employers’ side too. Compared to individual negotiations with individual employees, they reduce administration and bargaining costs regardless of the topic being addressed (cf. Ellguth/Kohaut 2022).

Collective bargaining agreements on CVET

In the case of a sectoral collective bargaining agreement, training provision is negotiated between the trade union and employer association and applies to all companies within the sector which are members of the employer association.* It is incumbent on the negotiating parties to decide which contents will be regulated, and they are protected in this regard by the right to form coalitions of economic interest and to collective bargaining autonomy (Article 9, Paragraph 3 German Basic Law [GG]). Collective bargaining agreements concluded must be recorded in the register maintained by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS) (cf. § 6 Collective Agreements Act [TVG]).

For example, a collective bargaining agreement relating to training (“TV Quali”) implemented between Südwestmetall (the employer association of the metal and electrical industry in Baden-Württemberg) and the trade union IG Metall in Baden-Württemberg contains an entitlement for an annual assessment of training needs and governs the process for agreeing the necessary training measures (IG Metall 2021). It also stipulates a procedure for the event that no agreement can be reached in this regard. Further regulations encompass assumption of costs and continued payment of wages.

Measurement of CVET participation and CVET agreements

The BIBB Training Panel incorporates various indicators of company-funded CVET. These include indicators which ascertain whether a company has funded CVET in the form of internal or external courses or programmes (hereinafter referred to as course-based CVET), meaning that at least one employee has taken part in company-funded course-based CVET (cf. Table 1 in the electronic supplement for the precise wording of this and of the following questions).

The number of participants in course-based CVET is also recorded. Employees are considered separately by level of task requirements, and three employee groups are differentiated. These comprise:

- employees performing unskilled tasks which usually do not require any vocational education and training;

- employees performing skilled tasks which usually require completion of vocational education and training or relevant occupational experience;

- employees performing highly skilled tasks, which usually require a degree from an institute of higher education/university of applied sciences or a master craftsperson, technician or comparable qualification.

The respective shares of employees who have taken part in course-based CVET can be calculated by the overall number of employees and their distribution across the three groups.

As well as collecting information on whether a company is covered by a collective bargaining agreement, the BIBB Training Panel (cf. Information Box) also includes a special module which surveys whether the sectoral, in-house or company agreement contains agreements relating to the promotion of CVET.

BIBB Training Panel

The BIBB Establishment Panel on Training and Competence Development is a representative annual survey of the training activities of companies in Germany. Companies are surveyed if they have at least one employee subject to mandatory social insurance contributions (referred to below as “employees”). The interview partners at the company are persons who are charged with human resources or training issues, e.g. heads of human resources, heads of training or executive managers.

A one-off special module on company co-determination was integrated into the 2015 wave of the survey. The following analyses are based on a sub-sample of companies covered by collective bargaining agreements (n = 2,142). A distinction is drawn within this sub-sample between companies with and without a CVET agreement.

The survey is conducted by the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB) in conjunction with the infas Institute for Applied Social Sciences and takes place using computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI).

Further information: www.qualifizierungspanel.de

How widespread are CVET agreements?

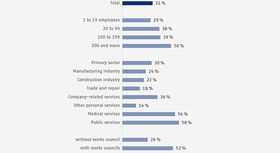

In approximately one third of companies covered by a collective bargaining agreement, such an agreement includes an agreement for the promotion of CVET (cf. Figure 1). Prevalence varies according to factors such as company size and sector. CVET agreements are more likely to be in place at companies with 200 employees and more (50%), at companies providing public services (58%) and at companies providing medical services (54%) than at smaller companies and at companies in the trade and repair sector (18%) or at companies in the construction industry (22%). They are twice as likely to be in place at companies with a works or staff council than at companies which have no representation of employees’ interests (52% versus 26%).

Higher participation in CVET at companies with a CVET agreement

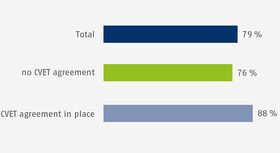

Participation of employees in course-based CVET is funded at 79 percent of companies which are covered by a collective bargaining agreement (cf. Figure 2). The share at companies with a CVET agreement is once again higher than at companies with no such agreement in place (88% versus 76%).

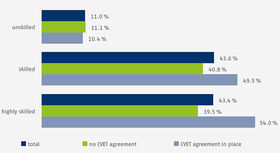

In this instance too, a consideration of the share of employees taking part in course-based CVET shows that this is higher at companies covered by a collective bargaining agreement than at companies which are not (cf. Figure 3). This is at least true of employees performing skilled and highly skilled tasks. The difference is very small in the case of employees performing unskilled tasks, and in this instance the share of participants at companies with a CVET agreement in place is even very slightly smaller than at companies without a CVET agreement. The share of employees performing unskilled tasks which takes part in course-based CVET is significantly lower in overall terms than the corresponding share of employees performing skilled or highly skilled tasks.

Do the positive correlations still stand if we control for relevant company and employee structural characteristics?

Results from multivariate regression analyses are stated below (a full list of the control variables is provided in the annotation to Figure 4) in order to exclude the possibility that the bivariate correlations presented in Figures 2 and 3 are based on underlying influencing factors which each correspond positively with CVET participation and with a CVET agreement, e.g. company size. A logistic regression model is estimated for the CVET participation model, i.e. the question of “whether” course-based CVET is funded in the company, because the dependent variable is only able to accept the values of 0 (= no) or 1 (= yes). Linear regression models are estimated (cf. detailed representation in Table 3 of the electronic supplement) for the models relating to the CVET rate, i.e. the question of “which share” of the employees (differentiated by three levels of task requirements) has taken part in course-based CVET. Figure 4 shows that, even if we control for extensive company and employee structural characteristics, CVET agreements are associated with a significantly higher likelihood that a company will fund course-based CVET (CVET participation, cf. Figure 4, dark blue).

The share of employees which takes part in course-based CVET (CVET rate) is also significantly higher at companies with a CVET agreement than at companies with no such agreement in place (cf. Figure 4, light blue, light green and green). CVET agreements are thus associated with significantly higher employee participation in CVET, even if we control for relevant company and employee structural characteristics. This fundamentally applies to employees at all three levels of task requirements. Nevertheless, the results indicate that employees performing unskilled tasks (cf. Figure 4, light blue) once again derive less benefit from CVET agreements compared to employees performing skilled or highly skilled tasks.

CVET agreements strengthen CVET participation – for some more than for others

The analyses exhibit positive correlations between CVET agreements concluded as part of collective bargaining agreements and participation in course-based CVET. This article thus provides indications that CVET agreements are a suitable instrument for the strengthening of CVET and can make a contribution to companies’ abilities to cover their skill demand.

Against the background that, in overall terms, employees performing unskilled tasks are less likely to take part in course-based CVET than employees performing skilled or highly skilled tasks, a positive evaluation should be made of the fact that they too benefit from CVET agreements, albeit less extensively. For reasons of data availability, the present article is unable to investigate the extent to which CVET agreements reinforce participation in further informal types of CVET and whether employees performing unskilled tasks benefit more greatly in this regard than other employee groups. Generally speaking, the question how access to different forms of CVET can be improved and secured, particularly for groups which have been disadvantaged and underrepresented up until now, is a relevant issue for future research.

The results are based on data from a special module which was surveyed on a one-off basis in 2015. This is a unique data source in Germany for the issue investigated in this article because it provides simultaneous data availability regarding a) CVET agreements concluded as part of collective bargaining agreements which apply within the company and b) participation by employees in course-based CVET. Against the background of a decline in the number of companies covered by a collective bargaining agreement whilst the significance of CVET continues to grow at the same time, it would be interesting to supplement the present article by using present data to map the current situation and investigate whether the results can be confirmed or have changed.

Literature

Czepek, J.; Dummert, S.; Kubis, A.; Leber, U.; Müller, A.; Stegmaier, J.: Betriebe im Wettbewerb um Arbeitskräfte. Bedarf, Engpässe und Rekrutierungsprozesse in Deutschland. Bielefeld 2015

Ellguth, P.; Kohaut, S.: Tarifbindung und betriebliche Interessensvertretung: Ergebnisse aus dem IAB-Betriebspanel 2021. In: WSI-Mitteilung 75 (2022) 4, pp. 328–337, DOI: 10.5771/0342-300X-2022-4-328

IG Metall: Tarifvertrag zur Qualifizierung 2021. URL: www.bw.igm.de/tarife/tarifvertrag.html?id=13654

Nimczik, J.: Betriebliche Weiterbildungsbeteiligung und Weiterbildungsquote. In: BIBB (Ed.): Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2024. Informationen und Analysen zur Entwicklung der beruflichen Bildung. Bonn 2024, pp. 301–303. URL: www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/bibb-datenreport-2024-final.pdf

Wotschack, P.; Solga, H.: Betriebliche Weiterbildung für benachteiligte Gruppen. Förderliche Bedingungskonstellationen aus institutionentheoretischer Sicht. In: Berliner Journal für Soziologie 24 (2014) 3, pp. 367–398. DOI: 10.1007/s11609-014-0254-7

Further links

Further information on operationalisation and on the regression is provided in the electronic supplement

(All links: status 17/03/2025)

Kathrin Weis

Academic researcher at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 1/2025): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin