The e-CF – a sector framework for professional competences in IT

Findings from the application of the e-CF in the modernisation of IT occupations

Angela Kennecke, Thomas Felkl

Sector frameworks are gaining in significance as part of the endeavour to make national qualification profiles more transparent in European comparative terms and to render them more readily understandable. The European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) represents just such an instrument for the IT sector. When the IT occupations were revised, it was used as a supplementary reference in order to map the skills, knowledge and competences contained in the new general training plans. This article provides an initial introduction to the development and structure of the e-CF. It also states the findings and outcomes that have emerged from the revision process and illustrates areas of potential for application and further development.

The e-CF – from birth to establishment as a full European Norm

In 2000, the European Council published the Lisbon Strategy with the aim of continuing to develop the European Union into a strongly knowledge-based economy and indeed into a knowledge society.1 Within the context of this strategy, it became apparent that there was a gap in demand for skilled workers with appropriate IT competences. This was viewed as being an impediment to the intended course of development. In March 2003, the European Commission initiated the European e-Skills Forum in order to bring together all relevant stakeholder groups with an interest in the topic of IT competences. The aims were to hear their views and to instigate a lively debate. The idea of creating a competence framework to encompass all skills relevant to IT specialists was born at a workshop held as part of the e-Skills Forum in 2004. The aims of such a meta framework were to facilitate the following:

- Make qualifications and certificates comparable across national borders and enhance their mutual recognition.

- Provide state bodies with a reference framework to increase permeability and interlinking of the various education and training opportunities.

- Offer schools and universities a canon of occupationally relevant e-competences (cf. European e-Skills Forum 2004, pp. 16 ff.).

The goal of these three functions was to help counter the shortage of skilled ICT workers in a more targeted way and at a European level. The framework was drawn up by a consortium comprising the network of the largest French IT companies CIGREF, the e-skills UK Sector Council, the Italian Fondazione Politecnico di Milano Foundation for Applied Research, representatives of the German APO-IT continuing training system from IG Metall and BITKOM and a number of prestigious international companies such as Michelin and Airbus. The first European e-Competence Framework was published in 2008. After being further developed on an ongoing basis, it was elevated to the status of a norm in 2016. The most recent version, which was also used for the alignment with the new German IT training occupations, appeared in 2019.

The structure of the e-CF

The standard essentially comprises four dimensions (cf. Table 1), which describe the minimum competence requirements in the workplace (cf. DIN EN 162341:2020-02, p. 64).

The first of these dimensions states the five e-competence areas (A. Plan, B. Build, C. Run, D. Enable and E. Manage) which correspond to the main business processes of organisations and companies.

The various competences within a competence area form the second dimension of the e-CF. A total of 41 competences are distributed across the five competence areas. These contain a generic description and are thus applicable to the different operational contexts. The third and fourth dimensions represent further details and supplementary information for each competence. The five proficiency levels for each competence are described in the third dimension. In fundamental terms, the five competence proficiency levels e1 to e5 of the c-CF are approximately matched to reference levels 3 to 8 of the EQF (cf. DIN EN 16234-1:2020-02, p. 64). e-CF level 2 is aligned to EQF levels 4 and 5, and level e3 is the equivalent of EQF level 6.

The fourth dimension presents samples of knowledge and skills in order to assist users in the implementation of the general competence descriptors and performance levels in practice.

In addition to this, the latest version of the e-CF defines seven transversal aspects. These encompass the cross-cutting topics of accessibility, ethics, ICT legal issues, privacy, security, sustainability and usability. The intention is that these topics should be addressed and integrated with regard to the respective subject matter of all 41 competences previously described.

Modernised and expanded – the new IT occupations

Although the IT adage “never change a running system” is sometimes justifiably cited, the reason why the IT occupations were able to endure for 18 years without being updated, a considerable period within the context of the sector, was the technologically neutral formulations they contained. This situation persisted until 2015, when a preliminary investigation into a process of realignment was launched

This modernisation was necessitated by the overall development in technology and methods, whilst the requirements of the knowledge age and the increased complexity of data systems and networks were also contributory factors.

The updating of the IT occupations was implemented across two stages. The first of these exclusively centred on an adjustment of the topic of IT security and data privacy (against the background of the GDPR). The second stage related to technical content and was concluded in the summer of 2019. This enabled the new IT occupations (see Information Box) to enter into force with effect from 1 August 2020. The task facing the experts was to replace the occupation of information technology officer with a new commercial occupation which would place the focus on shaping business models within the scope of the digital economy. The intention was that consideration would be accorded to cross-cutting IT activities, to digital systems and to cyber physical systems in particular, to big data and to the updating and enhancement of tried and tested contents.

All IT occupations continue to have common core skills, and practical examinations retain the company-based project work that is typical of the profession. Alongside the aspects stated above, the official instruction also included the indication that formulation of training contents should be matched against the e-CF with the aim of documenting the level achieved. Interesting parallels can be ascertained if we compare the main updates to the dual IT training occupations with the changes in the latest version of the e-CF. Business and technological developments, data science and analysis and the transversal competences in the e-CF reflect major commonalities of all dual IT occupations.

The new IT occupations

The result is that there are still two commercial IT occupations.

- Digitalisation manager (referred to in the table as KDM)

- IT system manager (KSM)

Two further specialisms (highlighted in italics) have been added to the occupational profile of information technology specialist, which has proven successful and has been retained.

- Application development (FIAE)

- System integration (FISI)

- Digital networking (FIDV)

- Data and process analysis (FIDPA)

The occupation of IT systems electronics technician is still available. In this case, a legal clarification has been put in place to the effect that the qualification confers the status of a skilled electrical worker.

How e-CF and the IT occupations come together

An initial matching was undertaken in 2019 at a time when the process of drawing up the general training plans had largely been completed and the new version of the e-CF was available. Documentation of the proficiency levels was not an end in itself. This process was undertaken in order to ascertain the effectiveness of the German IT training occupations. In the final matching stage, correlations between the occupational profile positions in the general training plan and the individual competences of the e-CF were identified by the respective expert for each occupation, including experts in the four specialisms that make up the training occupation of information technology specialist. This alignment was guided by the e-CF descriptions in dimensions 2 to 4. The greatest degree of correlation was sought at all times. It was important during this procedure to accord consideration to the respective overall context rather than merely comparing individual keywords or skills.

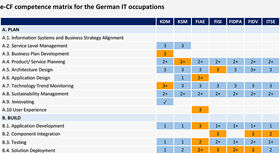

In the table, blue fields containing a tick indicate a competence that is in line with the general competence description (dimension 2) of the e-CF. As the matching process continued, several correlations in different e-competences and in their proficiency levels were generally found per occupational profile position. The reason for this is the holistic and employment-oriented way in which the occupational profile positions were viewed. Also frequently, occupational profile positions lay between two e-competence levels. These instances were denoted using the figure of the e-competence level fully achieved together with a plus sign.

The results for each occupation were transferred to a matrix in order to allow the alignments to be rapidly realised (cf. Table 2).

Looking at the IT occupations through the lens of the e-CF

A consideration of the final matrix clearly reveals various aspects of the training occupations, and these will be discussed below.

Each of the IT occupations forming an object of the present discussion offers a multitude of different competences for all main business processes (dimension 1 of the e-CF). Firstly, this broad spectrum of competences once again makes clear that the German IT occupations are capable of versatile deployment. Secondly, it shows that the skilled IT workers are prepared for cross-cutting work. When comparing the competence spectra of the occupations between one another, we see that the different occupations conspicuously exhibit the same proficiency levels in the case of many competences. This gives rise to the question as to whether the occupations might be too similar amongst themselves. One explanation for this is that such similarity is desired because the occupations contain a significant proportion of joint core skills. A second reason lies in the fact that the finer details of the occupational context cannot be fully mapped in the matrix. In order to remedy this defect, the profile-defining e-competences per IT occupation were identified in consultation with the experts. These were then marked with an orange background in the matrix.

If we turn our focus to the individual proficiency levels of the competences, it is apparent that many of the competences mapped exceed level e2 and thus correspond to reference level 6 of the EQF, at which Bachelor, technician and master craftsmen qualifications are localised. This may certainly be apposite in relation to tasks performed in the workplace, particularly when the international character of the norm is taken into account. The differing work cultures in individual countries definitely render it possible for one and the same task to be carried out by a trained skilled worker in one country whilst being executed by someone with an academic qualification in another.

The e-CF as an instrument for European understanding in the IT education and training sector?

The e-CF is a framework with the intended purpose of describing the minimum requirements made of jobs occupied by skilled ICT workers and ICT managers and therefore of ensuring transparency in respect of the competences which are demanded. By way of contrast, the occupational profile positions contained in the training regulations describe the qualification of a trained skilled worker by mapping the skills, knowledge and competences to be imparted.

During the course of training, methodological and social competences are also developed as a component of employability skills. The personal development which occurs leads to an occupational self-image and to an occupational identity. Over the period of training, trainees will perform activities and processes in an increasingly assured way. This results in a growth in self-determination and in the amount of responsibility they assume for their own actions. These implied ancillary effects are only partially discernible from the training regulations, but they also arise from within the scope of the Vocational Training Act and the historical development of the German occupational system. These aspects of vocationalism are the main elements which are not made visible via a mapping procedure carried out using the vehicle of the e-CF. A mere aggregation of IT competences is not sufficient in itself to create an IT professional. Although this deficiency in presentation cannot be resolved in the final analysis, the broad competence spectrum of the IT occupations enables us to draw the conclusion that these are based on solid foundations. Instances of vagueness in the way in which the occupations are depicted can also be discerned because, even if the matrix displays the same competence values, differences exist within the work context. This may arise as a result of differing degrees of complexity of the specific IT systems or may emanate from the area of effective technical scope (application, system, hardware, commercial perspective). However, this vagueness can largely be resolved as soon as the title of the specific IT training occupation is also taken into consideration. Translations are a further possible source of vagueness. In this regard, the e-CF offers the benefit of having been translated into various languages by IT specialists. This means that a high degree of accuracy of fit is in place. Nevertheless, when the German occupational titles were translated into English, the carefully chosen designations were inevitably diluted.

In addition to this, there are non-IT related training contents that cannot be covered by the e-CF. Examples here include commercial management and control in the case of the IT specialists, the electrical engineering competences of IT systems electronics technicians and in particular the training contents relating to the company and to employment law contained within the standard occupational profile positions. This gap is inherent within the very nature of a purely IT-specific sectoral framework and simply needs to be accepted.

The experiences gained from reconciliation with the e-CF make it clear that this is not suitable for a complete matching of the German IT training occupations. The main effect of the matching process is to provide guidance in terms of categorisation and discussion.

The work undertaken in connection with the European e-competence Framework at the end of the updating procedure was a useful addition in overall terms. The result is an extensive matrix, in which the German training occupation profiles and the competences acquired are recognisable at a glance. They can also be compared with and differentiated from one another. This information can be read within a reference system that is understood right across Europe. Such an approach assists all those who are poorly acquainted with the IT training occupations. It also opens up an opportunity to improve understanding of the German dual IT training occupations in other European countries.

This can provide a vehicle to support the mobility and acquisition of skilled workers, both within companies and organisations and between various employers, regions and countries. Whether this actually occurs in this way, however, remains to be seen. The matching also makes it easier for universities to credit competences acquired during training to higher education study contents.

The annex to the e-CF contains links to other frameworks, thus allowing the alignment to be transferred to these formats. Further new opportunities are being produced by the joint work on the e-CF standard being conducted in European countries (cf. TR16234-4 e-Competence Framework). Universities in France, for example, are seeking to offer digital learning and examination solutions that are matched to the competences of the e-CF. This could then also be used to supplement German vocational education and training.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that linking the German IT occupations with the e-CF mainly brings benefits. For this reason, the reconciliation drawn up has been made available as supplementary material for implementation guides in Germany as well as being included on the list of application scenarios for the e-CF (“Case Study E”). This increases the level of familiarity with the e-CF in the German vocational education and training system and also raises awareness of the German occupations within a European context. Ultimately, we must never disregard the fact that norms and methods have their limitations nor lose sight of the particular characteristics of the occupations.

-

1

www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_de.htm (retrieved: 29.09.2020)

Literature

DIN EN 16234-1:2020-02: e-Kompetenz-Rahmen (e-CF) – Ein gemeinsamer europäischer Rahmen für IKT-Fach- und Führungskräfte in allen Branchen. Teil 1: Rahmenwerk. Berlin 2020 – URL: www.beuth.de/de/norm/din-en-16234-1/317078638 (retrieved: 29.09.2020)

EUROPEAN E-SKILLS-FORUM: E-Skills for Europe: Towards 2010 and beyond. Brüssel 2004 – URL: www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/etv/Upload/Projects_Networks/Skillsnet/Publications/EskillForum.pdf (retrieved: 29.09.2020)

TR16234-4 e-Competence Framework (e-CF) – A common European Framework for ICT Professionals in all sectors – Part 4: Case Studies. To be published in 2021

ANGELA KENNECKE

IT Competence Manager and Works Council Member at Airbus in Bremen

THOMAS FELKL

Academic researcher at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 3/2020): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin