Financing of vocational education and training in Germany

Normann Müller, Felix Wenzelmann, Anika Jansen

German vocational education and training attracts a good deal of attention globally because it offers young people a good way of entering the employment system. However, what are the associated costs? Although precise determination of costs is difficult in methodological terms, this article attempts to address the issue.

Overview of financing

Three parties contribute towards the financing of vocational education and training in Germany:

- the companies,

- the public sector and

- the trainees themselves.

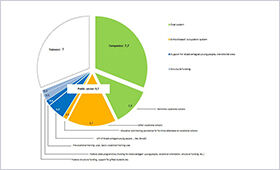

Figure 1 gives an overview of the sources and uses of financing.

In the training year 2012/13, costs to companies of providing company-based training were around Euro 7.7 billion. These costs exclusively relate to the dual training system. In the budget year 2013, total spending by all public bodies (Federal Government, federal states, Bundesagentur für Arbeit (BA) [Federal Employment Agency] was approximately Euro 9.7 billion. Public funding is used to finance the dual system, but also full-time vocational schools, the transitional system, and the structural development. No information is thus far available regarding the amount to which the trainees themselves participate in the financing of their training. Their contribution essentially comprises the loss of income they suffer as a result of their training compared to employment in an unskilled or semi-skilled capacity. Rough estimates made by BIBB indicate that the financing contribution made by the trainees is considerable and is consequently underestimated.

How are the amounts calculated?

Costs for companies are estimated via a BIBB survey conducted on a regular basis (cf. JANSEN et al. 2015).1 The most recent survey relates to the 2012/13 training year, and results were extrapolated using the trainee structure as of 31 December 2012. The figure presents net costs, i.e. the gross costs incurred by companies minus the value of the productive contributions of the trainees.

Companies also participate in school-based vocational education and training via such activities as supervising trainees during obligatory practical phases. We do not know for this type of training whether company training costs outweigh the productive contributions or whether the opposite applies, as is, for example, presumably the case with the occupations of nursery school teacher and geriatric nurse. The aggregated financing contributions made by trainees in the dual system can also be approximately assessed on the basis of the BIBB survey mentioned before.2 Assuming that trainees could, if they were full employees, earn the same wages as unskilled/semi-skilled workers in the observed companies, resultant losses of income are of a similar magnitude to the aggregated training costs of the companies. Those attending vocational school on a full-time basis are not included in the calculation. Their losses of income, at least at the level of the individual person, are likely to be significantly higher because no training allowance is paid.

The assumptions regarding relevant comparative wages give rise to considerable uncertainty in estimating losses of income. Comparative wages and loss of income would be overestimated if, for example, unskilled/semi-skilled workers at the companies covered by the BIBB survey have more occupational experience than the trainees. On the other hand, trainees are likely to be in possession of better personal qualifications, something which can alleviate or even (over) compensate for this effect. For this reason, Figure 1 is restricted to a schematic representation of magnitude. Other costs to be borne by trainees, such as those for learning or work materials or the fees school-based trainees are occasionally required to pay, are probably negligibly small compared to losses of income.

The presented figures pertaining to public spending relate to the 2013 budget year (cf. MÜLLER 2015). Public spending is focused on federal state-funded vocational schools. The official statistics, however, record spending only for vocational schools overall rather than separately for the individual types of school. Assuming that one lesson causes the same level of costs at all school types we allocate overall spending on vocational schools to the different school types based on the respective number of hours taught at each school type. The trade and technical schools, which primarily tend to form part of the continuing training system, are not included. The largest single share of spending is on part-time vocational schools in the dual system (around Euro 2.9 billion in 2013). Spending on individual types of school in the school-based occupation system, such as full-time vocational schools or specialised upper secondary schools, is lower although these schools together actually account for approximately Euro 3.7 billion. Transitional provision such as the prevocational training year and the basic vocational training year make up about Euro 0.4 billion.

In the school-based occupation system, the living costs of those attending vocational school on a full time basis are also funded pursuant to the Federal Education and Training Assistance Act (BAföG, approximately Euro 0.3 billion) alongside the financing of vocational schools. In the transitional sector, VET spending by the BA and the Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS) [Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs] together totals around Euro 1.3 billion and constitutes a further major segment.3 These costs relate to vocational orientation and preparation as well as to vocational education and training itself. A large part of BA funding is used to support trainees who are particularly disadvantaged, specifically trainees in publicly financed company-based training. The latter could also be said to be part of the dual system because it represents a substitute for company-based training and thus supplements the dual system. The same applies with regard to the vocational education and training assistance which trainees within the dual system receive in order to secure their living costs (approximately Euro 0.4 billion). Spending on the vocational education and training of disabled persons is not included in the figure.

The federal states continue to offer countless funding programmes which display a relation to vocational education and training. A rough estimate by BIBB put the value of these at around Euro 0.5 billion in 2013, whereby a causal correlation with the VET system not necessarily need to exist. Several programmes are in place to support infrastructures (such as inter-company vocational training centres, training for disadvantaged young people or vocational orientation). Other schemes are aligned towards economic policy and provide assistance to areas such as the small and medium sized enterprises (SME) sector. It is, however, unknown to what extent the funds are connected with initial or rather with continuing vocational education. The same applies to Federal Government spending on structural development, maintenance of infrastructures or support for gifted students, which also in some cases is connected with continuing vocational training.

Is the spending worthwhile?

Our remarks describe a complex financing system for vocational education and training in Germany. The question arises as to whether this expenditure is worthwhile. For all parties providing financing, however, such spending represents an investment which may in some cases only pay off at a significantly later point in time. Companies may, for example, save recruitment costs by taking on trainees at the end of their training. Trainees presumably expect a lower risk of unemployment or a higher income in future, and public authorities anticipate positive effects on social systems and on society as a whole.

-

1

Cf. also the explanations on extrapolation of costs at www.bibb.de/de/11060.php (retrieved 25.01.2016).

-

2

This rough calculation is based on data from the previous survey, which relates to the year 2007.

-

3

The “transitional area” encompasses all measures which provide preparation for entry to training and do not lead to a full vocational qualification.

Literature

JANSEN, A. et al.: Ausbildung in Deutschland weiterhin investitionsorientiert – Ergebnisse der BIBB-Kosten-Nutzen-Erhebung 2012/13 [Apprenticeship training in Germany remains investment-focused – results of the BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey]. BIBB Report Nr. 1/2015 – URL: www.bibb.de/en/25852.php (retrieved: 25.01.2016).

MÜLLER, N.: Ausgaben der öffentlichen Hand für Weiterbildung [Public spending on continuing training]. In: BIBB (Ed.): Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2015 [Data Report to accompany the 2015 Report on Vocational Education and Training]: Bonn 2015, pp. 275–278

NORMANN MÜLLER

Dr. Research Associate in the “Costs, Benefits and Financing of Vocational Education and Training” Division at BIBB

FELIX WENZELMANN

Research Associate in the “Costs, Benefits and Financing of Vocational Education and Training” Division at BIBB

ANIKA JANSEN

Research Associate in the “Costs, Benefits and Financing of Vocational Education and Training” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 2/2016): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin