Part-time vocational education and training – rarely chosen, yet good examination pass rates

Alexandra Uhly

Part-time vocational education and training in the dual system was regulated by law in 2005. Annual reporting has shown that very few part-time training contracts have thus far been concluded within the dual system. But how does vocational education and training unfold if trainees pursue it on a part-time basis? This article uses the Vocational Education and Training Statistics to analyse the success of part-time training contracts in 2018.

Part-time vocational education and training – the status quo

Part-time vocational education and training is a topic which has been and continues to be addressed within the scope of numerous initiatives and programmes. It is funded with the dual goals of avoiding unemployment (especially of persons with family responsibilities) and of countering a shortage of skilled workers. For a “broader consideration of part-time training in societal and educational policy terms” see for example Puhlmann et al. (2016). The possibility of part-time vocational education and training in the dual system, i.e. pursuant to the BBiG [Vocational Training Act]/HwO [Crafts and Trades Regulation Code], was regulated by law in 2005. Two essential aspects were emphasised in § 8 of the Vocational Training Act (in the version of the law which remained valid until 31 December 2019). The first of these was that there must be a “justified interest” on the part of the trainee. Such a justified interest was “deemed to be in place if, for example, trainees have to support a child of their own or a family member in need of care or if comparably important reasons apply” (BIBB Board 2008). Secondly, part-time vocational education and training was designated as a special case of shortening the training. It was therefore prerequisite that the training objective could also be achieved in a shorter time. Part-time training did not generally involve any extension of the total calendrical duration of training (duration of training in months). The possibility of extending training (§ 8 Paragraph 2 BBiG) only existed in exceptional cases where there was good reason to believe that the training objective could not be fulfilled in a shorter period (this proviso applied universally and was thus also relevant to part-time vocational education and training). The Vocational Education and Training Modernisation Act of 12 December 2019 (which entered into force on 1 January 2020) brought about a considerable change to these regulations (see below).

Part-time trainees

As we know from the Data Report to accompany the Report on Vocational Education and Training1, only very few training contracts within the dual system have previously been registered with the Vocational Education and Training Statistics as part-time contracts. A total of only 0.4 percent of new training contracts that entered into force in 2018 were concluded on a part-time basis. These represented fewer than 2,300 new contracts in dual vocational education and training (for development over the course of time, cf. Uhly 2020). This neither includes VET programmes that are not governed by the BBiG/HwO nor retraining courses within the dual system (for information regarding part-time vocational education and training in retraining programmes or in school-based VET, cf. Sammet 2020).

In 2018, 86.6 percent of part-time training contracts (new contracts) were concluded with women, who are thus significantly overrepresented compared to new contracts in overall terms (36.8%). Trainees who have not achieved a higher level than a lower secondary school leaving certificate are also disproportionately represented (part-time 38.3%, all newly concluded contracts 28.5%). By way of contrast, there is an under-representation of persons with an intermediate secondary school leaving certificate (part-time 37.7% as opposed to 41.9%) and of those in possession of a higher education entrance qualification (part-time 24.0%, overall figure 29.6%).2 Despite the lower level school leaving qualifications, the average age of part-time trainees concluding a new contract is significantly higher (part-time 26.0 years, overall average 19.9 years). Foreign trainees show similar percentages both in dual VET in overall terms and in part-time training (part-time 13.3%, overall figure 11.7%).

Vocational Education and Training Statistics

The Vocational Education and Training Statistics of the Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the federal states (referred to in abbreviated form as the Vocational Education and Training Statistics) include inter alia an annual survey of data relating to all dual vocational education and training contracts pursuant to the BBiG or the HwO.

Trainee data for the Vocational Education and Training Statistics has been collected in the form of a contract-related survey since 2007. Company-based retraining contracts are not included.

The Vocational Education and Training Statistics began to record the characteristic of “part-time vocational education and training” for VET contracts in the 2007 reporting year.

For details regarding the survey, indicators, etc., cf. www.bibb.de/dazubi and in particular Uhly (2019).

Source for the figures in this article: BIBB “Trainee Database” based on data from the Vocational Education and Training Statistics (survey as of 31.12.). Absolute values are rounded to a multiple of three for data protection reasons. Calculations by BIBB (simple proportions were calculated on the basis of rounded data).

Legal basis (for the reporting year analysed here): §§ 87 and 88 BBiG in the version of the law which remained valid until 31 December 2019.

Success of training – premature contract dissolutions and examination passes

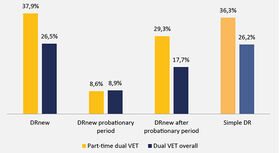

The dissolution rate provides an approximate value for the risk that a training contract which has been commenced will be dissolved. If we calculate the dissolution rate for part-time contracts, the current expectation is that the dissolution rate according to the BIBB quota cumulation model will produce a slight overestimation, whereas the simple dissolution rate will lead to an underestimation. For this reason, both rates are calculated in Figure 1 (for details, cf. Uhly 2020).

The contract dissolution rate for part-time training contracts is significantly higher than for dual vocational education and training as a whole. This particularly applies to the time following the probationary period. However, it is important to point out that the dissolution rate is not a personally related rate. If certain groups of persons display a higher risk of multiple contract dissolutions, this will cause a significant increase in the (contract-related) dissolution rate. A consideration of the proportion of dissolutions amongst the cohorts of training entrants in 2014 reveals significantly lower differences in the (personally) related dissolution rates between persons in part-time training and those in dual VET overall (ibid.). When interpreting this finding, consideration also needs to be accorded to the fact that certain groups of persons are disproportionately represented in part-time training contractual arrangements. The higher risk of dissolution is not caused by the part-time training in itself (ibid.).

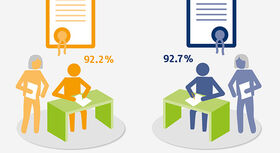

The Vocational Education and Training Statistics record examination success for all candidates. Due to an absence of continuous data, however, they do not include the training success of entire entrant cohorts. Although trainees with a lower secondary school leaving certificate are overrepresented amongst part-time training contracts, their success rates are similar to those achieved in dual vocational education and training in overall terms. 92.2 percent of candidates with part-time training contracts pass their final examinations. The pass rate across dual vocational education and training as a whole is virtually identical (92.7%, cf. Figure 2). This success rate is also achieved with a similarly low number of re-sits. In 2018, 6.3 percent of all final examinations in vocational education and training as a whole were re-sits. The corresponding figure for persons in part-time training was only 5.3 percent. If we use a multivariate model to control the fact that older trainees and trainees with a lower secondary school leaving certificate are overrepresented in part-time training contractual arrangements, then part-time training can even be shown to exert a positive effect on examination success (ibid.).

Will the Vocational Education and Training Modernisation Act create new opportunities?

Part-time training continues to be implemented to only a very limited extent within dual vocational education and training. The training success achieved by part-time trainees is ambivalent in nature. On the one hand, such training contracts are significantly more likely to be prematurely dissolved, although the part-time arrangements are not in themselves the cause of this. On the other hand, the examination pass rates of part-time trainees are just as high as those achieved across vocational education and training as a whole, despite school leaving qualifications which are lower on average and the stresses of family responsibilities. New statutory provisions have been introduced via the Vocational Education and Training Modernisation Act with the aim of expanding the dissemination of part-time vocational education and training.

Firstly, the potential group of persons is being extended (the statutory restriction regarding a “justified interest” has been removed). Secondly, part-time vocational education and training is no longer to be governed as a special case in respect of the shortening of the duration of training. The new regulations, which entered into force on 1 January 2020, thus automatically extend the calendrical duration of training if no additional application is made for reduction. It remains to be seen how part-time vocational education and training will develop in the wake of these new provisions. The notion that extension of the calendrical duration of training will in itself be sufficient to reduce the risk of dissolution appears unlikely. The supposition must be that this goal will not be achieved without further support measures. An improvement in the status of information and guidance with regard to funding opportunities may help bring about an expansion in part-time vocational education and training. More flexibility in the school-based part of dual VET is also being called for, because the intention is that the shortening of weekly or daily training time will only apply to the period of training spent at the company and not to the vocational school (cf. Sammet 2020; Linde 2019; Puhlmann et al. 2016). Ongoing support during training also appears to be of particular significance given the comparatively high risk of contract dissolution.

Literature

BIBB-HAUPTAUSSCHUSS: Abkürzung und Verlängerung der Ausbildungszeit/Teilzeitausbildung. Empfehlung vom 27. Juni 2008

LINDE, K.: Ausbildungswege in Teilzeit – Herausforderungen und Erfahrungen in NRW. In: BWP 48 (2019) 1, S. 34-37

PUHLMANN, A. u.a.: Vereinbarkeit von Ausbildung und Familie – 10 Jahre Teilzeitausbildung im BBiG (§ 8). Abschlussbericht. Bonn 2016

SAMMET, U.: Teilzeitausbildung. Ein bislang wenig bekanntes Ausbildungsmodell mit neuen Chancen. 2020 – URL: www.ueberaus.de/gastbeitrag-teilzeitausbildung (retrieved: 27.02.2020)

UHLY, A.: Erläuterungen zum Datensystem Auszubildende (DAZUBI). Hinweise zu den einzelnen Berichtsjahren. Bonn 2019

UHLY, A.: Teilzeitberufsausbildung in der dualen Berufsausbildung – Strukturen, Entwicklungen und Ausbildungsverlauf. Empirische Analysen auf Basis der Berufsbildungsstatistik. Bonn 2020 (in preparation)

Further Reading

Detailed analyses conducted by the author of the course of training and of structures and developments of part-time vocational education and training in the dual system can be found in UHLY (2020).

ALEXANDRA UHLY

Dr., academic researcher at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 2/2020): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin