Graduate surplus and skilled-worker shortage: Trends in the vocational qualification structure

Felix Bremser, Anna C. Höver, Manuel Schandock

For some considerable time, Germany's vocational qualification structure has shown a trend in the direction of higher qualifications. According to the OECD, however, graduate numbers are still very low in Germany by international comparison and it calls for them to be raised. This article sets out the possible consequences of a one-sided increase in the graduate ratio for the development of the qualification structure of the German population as a whole. To this end, trends in student numbers and transitions between the different qualification segments will be examined. Graphs are used to show the qualification supply and demand trends since 1996 and to carry out projections up to the year 2030 with the help of appropriate model-based calculations.

The call to raise graduate ratios

For those who subscribe to the OECD's analysis, growth in higher education qualifications is proceeding too slowly in Germany compared with other countries. Although Germany's proportion of university graduates has more than doubled from 1995- to 2010 (from 14% to 29%), it remains below the OECD average (39%) and is therefore deemed not to be keeping pace with the demand for highly qualified individuals. In contrast, stronger growth has been recorded in other OECD countries (e.g. Slovakia 15% to 61%; Portugal 15% to 40%, cf. OECD 2011).

The OECD's call for higher graduate ratios in Germany is also viewed critically in various quarters. One focal aspect of this criticism is that no account is taken of the specifics of the German vocational education system. The fact that no equivalent system exists in other countries renders comparisons more difficult. For instance, there are qualifications provided within the German dual system of vocational education (e.g. in the IT sector), the content of which is taught in other countries as part of a university or advanced technical school training (cf. BOSCH 2010). If this fact were taken into account when calculating Germany's graduate ratio, it would be more closely aligned with the OECD average. International comparisons must make allowance for differences between educational and vocational systems, because the German education system makes use of both vocational and academic pathways to supply personnel to fill highly demanding positions (cf. MÜLLER 2009). Accordingly, a sizeable share (41 %) of people employed in core occupations in knowledge-intensive sectors hold a vocational qualification at ISCED level 4a (cf. LESZCZENSKY/GEHRKE/HELMRICH 2011, p. 42; for an explanation of the ISCED levels cf. BOHLINGER in this issue of BWP.

Trend in student numbers

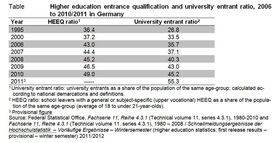

The latest figures from the Federal Statistical Office show that transitions into higher education institutions have steadily increased (cf. Table). In parallel with the rise in the higher education entrance qualification (HEEQ) ratio, the ratio of new university entrants has also risen since the mid-1990s. The university entrant ratio shows a more pronounced rise, with growth from 2010 to 2011 almost equalling that for the period 2006 to 2010.

The debate on graduate ratios is always bound up with the issue of demographic change and the shortage of skilled workers. In view of declining birth rates, overall numbers of school leavers in Germany are now falling. Since the annual number of school leavers holding a higher education entrance qualification is likely to settle at its current level for the next few years, this could lead to increased competition between the vocational and academic pathways to recruit these individuals (cf. LEZCZINSKY et al. 2012 p. 31 f.). Analyses conducted by BIBB, however, show that the composition of the workforce is not driven exclusively by trends in the general school system.

Transitions between qualification sectors

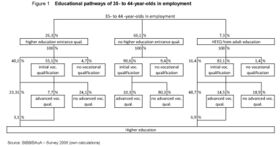

The following charts describe the transitions between the various qualification levels, and show their quantitative significance within the vocational education system, comparatively for different age cohorts.1 By way of illustration, Figure 1 shows the transitions of 35- to 44-year-old members of the workforce reaching the next level of the education system. The total on each level equals the share of individuals on the preceding level. Qualifications need not necessarily have been acquired in the sequence shown here.

The chart reveals some pathways involving multiple qualifications such as the combination of an initial and an advanced vocational qualification and/or a university degree. Apart from this form of double or triple qualification, dual vocational training opportunities in the tertiary sector (dual study courses at universities of applied sciences or universities of cooperative education) provide additional training pathways where multiple qualifications are gained concurrently rather than consecutively (cf. SPANGENBERG/BEUßE/HEINE 2011, p. 121 f.). These are not, however, included in the present analysis.

Figure 1 shows individuals with a higher education entrance qualification (HEEQ), individuals with a second-chance HEEQ, and individuals with no HEEQ. For the latter, there is a "third education pathway" which provides mature learners with certain opportunities to commence a university degree, but it has long been the case that the numbers embarking on degrees via this route are very low as a percentage of the total student population. Since the year 2009, however, access to academic education has been widened to include vocationally qualified individuals without an HEEQ. For this reason a growing increase in take-up can be expected (cf. ULBRICHT 2012).

Among 35- to 44-year-olds in employment, 40.2% of those with an HEEQ (excluding second-chance HEEQs) have acquired a university degree without gaining any further qualification. This percentage is slightly lower in the cohort of 25- to 34-year-olds (38.8 %) and significantly higher in the cohort of 45- to 55-year-olds (51.7 %). It therefore seems that initial vocational training is increasingly preferred over university studies. Of the 35- to 44-year-olds with an HEEQ, however, only 28.7% of those who complete an initial vocational qualification end up without a higher education degree (24,1+7,7-3,1). In the 45- to 55-year-old cohort this figure is as low as 20.3%. Many of the individuals under consideration here may have accomplished a transition into the academic qualification sector.

It is seen that the majority of working 35- to 44-year-olds without an HEEQ (90.6%) have completed an initial vocational qualification, the share being higher in the 25- to 34-year-old cohort (91.9%) and lower in the 45- to 54-year-old cohort (88.6%). Holders of an initial voca-tional qualification in the 35- to 44-year-old and 45- to 54-year-old cohorts have more frequently gained an upgrading qualification (10.3% and 8.2% respectively) than those in the youngest age group (4.4%). Here it must be noted that people often wait until later in life to undertake upgrading training.

Finally, looking at working people with a second-chance HEEQ, a high proportion hold a full initial vocational qualification (between 79% and 87%). Of these, 35% in the 25- to 34-year-old cohort and 55% in the 45- to 54-year-old cohort have gained a degree from higher education. Falling between these two figures, a 47.8% share of 35- to 44-year-olds have gained a degree. This indicates that they obtained their HEEQ during initial vocational training or immediately afterwards, and only then commenced university studies.

The analysis shows that initial vocational qualifications hold considerable appeal in comparison to university degrees, even for people with an HEEQ, and are quite frequently undertaken in addition. However, it also seems clear that many of them leave the intermediate qualification tier. The same is apparent for those who have acquired a second chance HEEQ, and in these cases the phenomenon would add to the bottleneck at skilled-worker level. When shaping transitions in the education system, politics and industry should focus greater attention on the training of skilled workers rather than almost exclusively on increasing graduate ratios.

Information on source data and methods

Microcensus and QuBe projections: The BIBB-IAB Qualification and Occupational Field Projections (HELMRICH, ZIKA 2010) are a coordinated projection of supply and demand on the basis of commonly defined occupational fields and datasets. The source data is taken from the Microcensus, the official representative statistical data on the population and labour market compiled by the Federal Statistical Office, in which one per cent of all German households participate every year, adjusted to the parameters of the German national accounts (cf. BOTT et al. 2010). Further information (in German) at: www.QuBe-Projekt.de.

BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey: The BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey for 2005/2006 is a (telephone-based, computer-supported) representative survey of 20,000 employed people in Germany, conducted jointly by BIBB and the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA). Further information (in German) at: http://www.bibb.de/de/2892.php

Status quo: Supply overhangs at all levels

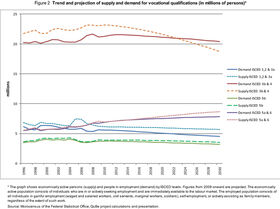

On analysis of the supply and demand of occupational qualifications, the trends from 1996 to 2008 show that demand on all tiers of qualification is more than met (cf. Fig. 2). In fact, when it comes to vocational qualifications (ISCED 3b, 4), supply considerably exceeds demand. Both demand and supply of qualifications at level 5b (master craftsman, supervisor, technical engineer) are roughly static. Supply and demand are plotted very close together although demand is fractionally below supply.

Nor is any qualification gap found as yet in the academic sector (ISCED 5a & 6). It is evident that in these two sectors, vocational education and academic education, supply and demand rise steadily over time, albeit with minor dips. In contrast, both demand and supply of individuals without a vocational qualification (ISCED levels 1-3a) are declining, so that people in this group have the poorest employment prospects (cf. BRAUN et al. 2012).

The trend to date is more indicative of bottlenecks in tertiary qualifications (ISCED 5a+6 and 5b) and a surplus of vocationally qualified individuals. But even now, shortages of the latter also occur in particular occupations, such as electrical device makers, chemical plant workers, machine fitters or dental technicians (cf. ERDMANN/SEYDA 2012).

Skilled-worker shortage and graduate surplus

As a result of the demographic trend, between 2010 and 2030 approx. 19 million economically active persons will retire from the German labour market whereas only approx. 15.5 million will enter it for the first time. That said, these new entrants are not distributed proportionately across all tiers of qualification (cf. HELMRICH et al. 2012, p. 5).

The qualifications trend up to 2030 reveals a clear picture. Supply and demand of ISCED levels 5a and 6 rise steadily. From around 2019, however, supply will significantly exceed demand, which implies a surplus of graduates. Supply and demand of ISCED level 5b both remain at about the same level, but here too, supply will be slightly above demand. On the other hand, at about the same time, supply of the intermediate qualification tier will decline while demand remains more or less static. At this point a gap opens up, with the downturn in supply setting in as early as 2013. Different vocational fields will be affected to varying degrees by the skilled-worker shortage (cf. HELMRICH et al. 2012, p. 11).

ISCED levels 1, 2 and 3a decline on both the supply side and the demand side, although supply continues to be higher than demand. The employment prospects for the persons concerned will therefore be even worse in future. This is where early remedial opportunities exist (for instance by means of second-chance qualification programmes supported by politics and industry) to harness the required potential for the middle-grade tier of skilled workers and thereby at least to mitigate the impending skilled-worker shortage.

From the current perspective, the future gap between supply and demand would be largest for those with vocational qualifications. The supply of qualifications at levels 5a and 6 meets demand up to 2016 almost perfectly, but clearly exceeds it from 2022. Thus there is no need for an expectation of a shortage of graduates.

Keep offering attractive dual vocational options

If the graduate ratio in Germany were to be raised, as the OECD has called for, the situation would become even more explicit than illustrated above. Around the year 2020 there will be a clear surplus of graduates, whereas skilled workers will be in short supply. These divergent perspectives result primarily from the fact that the OECD fails to take into consideration the peculiarities of the German vocational education system. More attention should be paid in comparative studies to these international variations in educational practices. A stronger orientation towards academic education would aggravate rather than alleviate the future problems of deploying qualifications in Germany. The German system of dual vocational training is popular with both companies and trainees. Most young people still embark on a dual programme of initial vocational training straight after their school careers, although transition analyses show that afterwards they are frequently unavailable to the training market on the intermediate qualification tier because they have instead progressed straight to university. Therefore, politics and business - instead of increasingly pinning their hopes on academic education - should upgrade the qualifications of low-qualified individuals, on the one hand, and endeavour to ensure the continuing appeal of dual initial vocational training, on the other. Rather than heightening competition between educational pathways, efforts should be directed towards greater complementarity. In particular, more emphasis could be placed on the opportunities to obtain a higher education entrance qualification via initial and advanced vocational training pathways, so that young people increasingly consider these routes when making their educational choices. These options would need to be further extended with a view to improving permeability between the education and training sectors, so as to enable the flexible planning of lifelong learning.

Literature

BOSCH, G.: Echte oder "gefühlte" Akademikerlücke? Anmerkungen zur Entwicklung der Berufs- und Hochschulausbildung in Deutschland. In: IG METALL (ed.): Akademisierung von Betrieben - Facharbeiter/-innen ein Auslaufmodell? Workshop Dokumentation. Frankfurt a. M. 2010, pp. 29-46 - URL: www.gew-nrw.de/uploads/tx_files/Experten_Workshop_Dokumentation_05_2010.pdf (viewed: 05.06.2012)

BRAUN, U. et al.: Erwerbstätigkeit ohne Berufsabschluss - Welche Wege stehen offen? BIBB Report 17/2012 - URL: www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/BIBBreport_17_12_def.pdf (viewed: 05.06.2012)

BOTT, P. et al.: Datengrundlagen und Systematiken für die BIBB-IAB Qualifikations- und Berufsfeldprojektionen. In: HELMRICH, R.; ZIKA, G.: Beruf und Qualifikation in der Zukunft. Bonn 2010, pp. 63-80.

ERDMANN, V.; SEYDA, S.: Fachkräfte sichern. Engpassanalyse. (BMWi) Berlin 2012 - URL: www.iwkoeln.de/de/studien/gutachten/beitrag/84059 (viewed: 05.06.2012)

HELMRICH, R.; ZIKA, G.: Beruf und Arbeit in der Zukunft - BIBB-IAB-Modellrechnungen zu den Entwicklungen in den Berufsfeldern und Qualifikationen bis 2025. In: HELMRICH, R.; ZIKA, G (eds): Beruf und Qualifikation in der Zukunft. Bonn 2010, pp. 13-62

HELMRICH, R. et al.: Engpässe auf dem Arbeitsmarkt: Geändertes Bildungs- und Erwerbsverhalten mildert Fachkräftemangel. Neue Ergebnisse der BIBB-IAB-Qualifikations- und Berufsfeldprojektionen bis zum Jahr 2030. BIBB-Report 18/2012 - URL: www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/a12_bibbreport_2012_18.pdf (viewed: 05.06.2012)

LESZCZENSKY, M.; GEHRKE, B.; HELMRICH, R.: Bildung und Qualifikation als Grundlage der technologischen Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands. Studien zum deutschen Innovationssystem, No. 1-2011. Hannover 2011 - URL: www.his.de/abt2/quer/que01 (viewed: 05.06.2012)

LESZCZENSKY, M.; CORDES, A.; KERST, C.; MEISTER, T.: Bildung und Qualifikation als Grund-lage der technologischen Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands. Studien zum deutschen Innovationssystem, No. 1-2012. Hannover 2012 - URL: www.his.de/abt2/quer/que01 (viewed: 05.06.2012)

MÜLLER, N.: Akademikerausbildung in Deutschland: Blinde Flecken beim internationalen OECD-Vergleich. In: BWP 38 (2009) 2, pp. 43-46 - URL: www.bibb.de/bwp/akademikerquoten (viewed: 05.06.2012)

OECD: Bildung auf einen Blick [Education at a Glance] 2011. Bielefeld 2011

SPANGENBERG, H.; BEUßE, M.; HEINE, C.: Nachschulische Werdegänge des Studienberechtigtenjahrgangs 2006. Dritte Befragung der studienberechtigten Schulabgänger/innen 2006 3 ? Jahre nach Schulabschluss im Zeitvergleich. HIS Forum Hochschule 18/2011. Hannover 2011 - URL: www.his.de/pdf/pub_fh/fh-201118.pdf (viewed: 05.06.2012)

ULBRICHT, L.: Stille Explosion der Studienberechtigtenzahlen - die neuen Regelungen für das Studium ohne Abitur. In: BWP 41 (2012) 1, pp. 39-42 - URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/id/6822 (viewed: 05.06.2012)

FELIX BREMSER

Student assistant in the “Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment” Division at BIBB

ANNA C. HÖVER

Student assistant in the “Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment” Division at BIBB

MANUEL SCHANDOCK

Research associate in the “Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 4/2012): Global Sprachteam Berlin

-

1

25-34 years, 35-44 years and 45-55 years.