Men and women amongst themselves

Gender-specific developments in dual male and female occupations and differences during training

Stephan Kroll

A sharp decline in female participation in the dual vocational system pursuant to the Vocational Training Act (BBiG) or the Crafts and Trades Regulation Code (HwO) has been evident since the start of the 1990s. By 2019, the number of women as a proportion of all trainees had fallen by five percentage points. In the area of responsibility of trade and industry, it was even the case that a decline of just under eight percentage points was recorded. What impact is this having on developments in occupational structure? This article uses the Vocational Education and Training Statistics to illustrate how the ratio of occupations dominated by men or by women has shifted over the past three decades. It also investigates which differences in training success may emerge as a result of such an unequal distribution of the genders.

Proportion of women in the dual system has been falling since the early 1990s

Foto-Download (Bild, 216 KB)

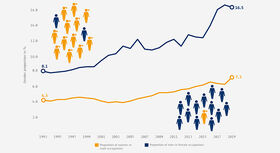

We have seen that participation in dual vocational education and training by young women and men has increasingly diverged over recent years. Demographic changes are one reason for this. Although the number of school leavers declined equally for both genders during the period from 2004 to 2019, increased immigration from the mid-2010s onwards primarily led to an increase in the number of young men seeking to enter dual training. This compensatory effect did not occur to the same extent amongst women. A second reason is the fact that young women are increasingly turning to training provision outside the dual system (cf. DIONISIUS/KROLL/ULRICH 2018). Accordingly, the number of young women as a proportion of all trainees in VET has fallen significantly since the beginning of the 1990s (2019 compared to 1993, -5.1 percentage points). This has occurred in virtually all areas of responsibility.

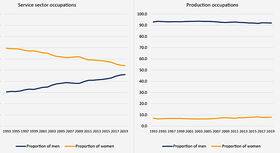

The developments described have also obviously had impacts in terms of occupational structure. A sharp withdrawal of women from service sector occupations (by more than 15 percentage points) has been evident since 1993 (cf. Figure 1). These occupations, which traditionally tended to be exercised by females, are increasingly being taken up by male trainees. Female trainees, however, have not at the same time made any inroads into male-dominated production occupations. This indicates that a shift may have taken place in the ratios of typical dual female and male occupations, at least in part.

Database and methodological approach

“Vocational Education and Training Statistics” database

The Vocational Education and Training Statistics of the Federal Statistical Office and the Statistical Offices of the Federal States constitute a total annual survey of data relating to dual vocational education and training pursuant to the Vocational Training Act (BBiG) or the Crafts and Trades Regulation Code (HwO). The trainee data from the Vocational Education and Training Statistics (data record type 1) enables deeply structured occupational, regional and group of persons-related differentiations to be performed.

The source for the figures presented in this article is the BIBB “Trainee Database” comprising data from the Vocational Education and Training Statistics (survey as of 31.12) for the reporting years from 1993 to 2019 (cf. www.bibb.de/dazubi).

Methodological approach for the classification of female, male and mixed occupations

- Female occupations in which the proportion of women is at least 80 percent

- Male occupations in which the proportion of men is at least 80 percent

- Mixed occupations in which neither gender reaches a proportion of 80 percent

The boundaries for the classification of female, male and mixed occupations have been set quite high both in order to create a clear delineation and to facilitate comparability with earlier publications (cf. DIONISIUS/KROLL/ULRICH 2018).

For the purpose of carrying out calculations for the three occupational groups, occupations surveyed in the Vocational Education and Training Statistics were collated by areas of responsibility and specialisms (including predecessor occupations where relevant).

Proportion of typical female occupations is in decline

An observation of the development of female, male and mixed occupations between 1993 and 2019 reveals that the number of female occupations has reduced further. This contrasts with quite a clear increase in male occupations. In light of the developments described at the start of the article, this is not surprising as far as the female occupations are concerned. If young men are more likely to conclude new training contracts in the service sector, then impacts will also be exerted at the level of the individual training occupations. And, in some cases, this may mean that a typical female occupation becomes a mixed occupation. As Table 1 shows, intensification of the updating system since 1996 has been a contributory cause to the significant rise in typical male occupations. Of the 103 male occupations in the 2019 reporting year, 30 are new occupations which have been created since 1996. With regard to the female occupations, this applies to a single occupation only. In overall terms, an examination of the occupational sectors in 2019 continues to display traditional distributions. More than 80 percent of the typical male occupations are in the production sector, whilst over 80 percent of the typical female occupations are to be found in service industries.

| 1993 | 2019 | Of which for 2019: new occupations since 1996** |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female occupations (proportion of women >_ 80%) | 24 | 20 | 1 |

| Male occupations (proportion of men >_ 80%) | 78 | 103 | 30 |

| Mixed occupations (no gender >_ 80%) |

53 | 77 | 20 |

| Occupations in total* | 155 | 200 | 51 |

|

*In order to avoid random effects in these and in further calculations because numbers of trainees are too small, account was taken only of dual training occupations for which there were at least 100 newly concluded training contracts in the respective year. Not including occupations for persons with disabilities (pursuant to §66 BBiG/§42 m HwO). **Differentiation by new and modernised dual training occupations (in accordance with BBiG/HwO) has been applicable since 1996, the year in which the updating system was intensified. All training occupations newly created since 1996 (and their successor survey occupations) are usually designated as being new if their training regulations do not abrogate a predecessor occupation pursuant to the BBiG/HwO. Source: BIBB “Trainee Database” |

|||

Proportion of men in female occupations has risen more sharply over the years than the proportion of women in male occupations

Foto-Download (Bild, 234 KB)

It will now be interesting to look at how the gender proportions in male and female occupations respectively have changed over the course of time. The occupations for the 1993 reporting year, listed in Table 1, serve as the basis in this respect. The relative gender proportions per occupation have been determined for the year 1993. Occupations were then allocated to a group on this basis, and the gender proportions in the occupation were averaged over the years for the respective group. The advantage of this approach is that each occupation selected informs the calculations equally regardless of the number of trainees it attracts.

Figure 2 shows that the proportion of men in typical female occupations more than doubled over the period observed. Nevertheless, the proportion of women in male occupations has also risen over recent years, albeit not in the same strong way and from a lower base. Immigration by predominantly male refugees, a substantial percentage of whom progressed into the service sector, is also likely to have been co-instrumental in the particularly significant increase in the proportion of men in female occupations from 2015 onwards (cf. DIONISIUS/ KROLL/ULRICH 2018). Although the proportion of men in the mixed occupations has risen slightly over the course of time, it remains virtually equal with the proportion of women (2019: men 52% as opposed to women 48%).

In overall terms, it is possible to interpret the developments observed as indicating that the classic career choice structures of men and women are slowly softening, even if this process is proceeding somewhat more clearly on the part of men. Notwithstanding this, significant proportions of today’s young men and women still opt for a gender-specific training occupation. Gender stereotypes play a crucial role here. Because of their age, young people feel the need to belong to a group and correspond to the norm (cf. ERIKSON 1968). As far as finding an occupation is concerned, this means that a particular focus is placed on occupations which are mostly exercised by those of the person’s own gender since this reinforces a sense of belonging (cf. GOTTFREDSON 2002).

Differences in the course of training in the event of non-gender typical career choice

Group membership and the collective spirit do not, however, merely play a part in finding an occupation. Impacts may also be unfurled at the company for young women and men who find themselves in a minority situation by dint of a non-gender typical career choice. If such a minority situation causes them to call the behavioural standards of their own gender into question, this may lead to insecurities and subsequently cause greater social tensions within the framework of the training (cf. ALTHOFF 1992). The analyses of ALTHOFF show that growing differences between gender proportions in an occupation means that the differences in contractual dissolutions will increase to the detriment of the minority gender. ROHRBACH-SCHMIDT/ UHLY (2015) also carried out a more detailed study of the topic of contractual dissolutions, in which they were able to show that no major risk of contract dissolution is associated with gender alone but that the opposite probably applies in the event of non-gender typical VET.

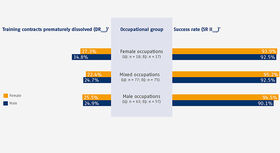

This is also demonstrated in Figure 3. Dissolution rates for women are below those for men, except in typical male occupations. The difference displayed in the case of men in typical female occupations is, however, much more distinct. In this instance, the average dissolution rate is the highest by some considerable distance (34.8%). If we assume that the minority situation is exerting an effect, then such an impact is evidently more clearly pronounced in the case of men in female occupations.

As far as the course of training in overall terms is concerned, it is revealed that women in mixed occupations are the most successful. This occupational group has the lowest dissolution rate and also enjoys the highest success rate – more than 95 percent. While this also applies to men, it is to a lightly weaker extent. One surprising fact is that the men’s success rate in the typical female occupations is just as high as in the mixed occupations (92.5%). On the other hand, it is clear that no benefits emerge from their majority situation because male occupations are those in which they perform the worst (success rate of 90.1%). Women produce significantly better results in male occupations, where they achieve a success rate of 94.5%.

Reducing company obstacles and expanding young people’s view

The analyses show that the boundaries of typical gender domains – given the restrictions stated above – have been slowly but steadily softening in the dual VET system over the past few years. This development could continue into the future, even if the proportion of women in the dual system should fall further, if an increasing presence of women in male occupations and of men in female occupations is able to foster the process of finding an occupation in a non-gender typical way and if this process thereby increasingly loses its “non-typical” character. In future, this would reduce trainees’ prior reservations about discovering themselves to be the only woman or only man. If nothing else, this would be a desirable goal for men, since it has been shown that they face a significantly increased risk of contract dissolution in the event of a non-typical career choice.

All stakeholders involved will need to take part in driving forward this development. Family environment is one of the factors which plays a major role in finding an occupation. Studies prove that young adults usually seek out role models of the same gender and that many of these are to be found within their own families. This gender-stereotypical choice of role models is even more clearly pronounced amongst boys than amongst girls (cf. AESCHLIMANN/HERZOG/MAKAROVA 2015). For this reason, it is important that parents help their children to look beyond gender stereotypes when finding an occupation.

However, merely simplifying access to non-gender typical occupations will not be sufficient for the further breaking down of gender-specific occupational structures. The focus will also need to shift to factors within the company environment, especially with regard to the contract dissolution risk. Studies conducted in recent years have shown that companies still harbour reservations towards women in male occupations and men in female occupations (cf. BEICHT/WALDEN 2014; IMDORF 2005). These need to be further reduced in future.

In addition to this and with an eye to new and modernised training occupations, future investigations should take place as to whether and how action can be taken to counter the existing structural disparity of male, female and mixed occupations and to see whether occupational profiles can be more closely aligned to gender main streaming.

Literature

AESCHLIMANN, B.; HERZOG, W.; MAKAROVA, E.: Bedingungen für eine geschlechtsuntypische Berufswahl bei jungen Frauen. Ergebnisse aus einem Forschungsprojekt. In: Die berufsbildende Schule 67 (2015), pp. 173–177

ALTHOFF, H.: Frauen in Männer-, Männer in Frauenberufen – Weibliche und männliche Jugendliche als Minderheiten in Ausbildungsberufen. In: BWP 21 (1992) 4, pp. 23–30 – URL: www.bwp-zeitschrift.de/de/bwp.php/de/bwp/show/14418

BEICHT, U.; WALDEN, G.: Berufswahl junger Frauen und Männer: Übergangschancen in betriebliche Ausbildung und erreichtes Berufsprestige (BIBB-Report 04/2014). Bonn 2014

DIONISIUS, R.; KROLL, S.; ULRICH, J.-G.: Wo bleiben die jungen Frauen? Ursachen für ihre sinkende Beteiligung an der dualen Berufsausbildung. In: BWP 47 (2018) 6, pp. 46–50 – URL: www.bwp-zeitschrift.de/de/bwp.php/de/bwp/show/9484

ERIKSON, E.: Identity. Youth and Crisis. New York 1968

GOTTFREDSON, L.: Gottfredson‘s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation. In: BROWN, D. (Ed.): Career Choice and Development, 4. Aufl. San Francisco 2002, pp. 85–148

IMDORF, C.: Schulqualifikation und Berufsfindung. Wie Geschlecht und nationale Herkunft den Übergang in die Berufsfindung strukturieren. Wiesbaden 2005.

MATTHES, S.: Warum werden Berufe nicht gewählt? Die Relevanz von Attraktions- und Aversionsfaktoren in der Berufsfindung. Bonn 2019

ROHRBACH-SCHMIDT, D.; UHLY, A.: Determinanten vorzeitiger Lösungen von Ausbildungsverträgen und berufliche Segmentierung im dualen System: eine Mehrebenenanalyse auf Basis der Berufsbildungsstatistik. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 67 (2015) 1, pp. 105–135 – URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-014-0297-y

(All links: status 1/12/2021)

STEPHAN KROLL

Academic researcher at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 4/2021): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin