Recording informally acquired competences

Making use of the impetuses emerging from European projects

Gesa Münchhausen, Ulrike Schröder

Informally acquired competences are playing an increasing role within a large number of training contexts in Germany, Europe and across the entire world. It has been widely accepted that such competences represent an important resource and that their recognition constitutes a considerable area of potential for society. This particularly applies to the educational system in Germany, which has previously tended to be aligned towards formal qualifications. The present paper sheds light on current developments in the field of recognition and validation of informally acquired competences. By using selected examples we hope to demonstrate the potential of European development and transfer projects supported in the framework of the EU LEONARDO DA VINCI Programme which could provide an impetus for further developments in Germany.

Contents of page

- Informally acquired competences - a European issue

- On the situation in Germany

- Synergies between German and European initiatives

- Daring to look beyond our own horizons and reaping the benefits of doing so

- Literature

Informally acquired competences - a European issue

Records show that many European countries have dealt extensively with the recognition of informally acquired competences, particularly since the 1990's. Such recognition often takes place in the wake of reforms to the respective VET systems. In the United Kingdom, for example, the aim of introducing National Vocational Qualifications (NVQ) was to enhance the value of skills and competences acquired outside the formal educational system. The vocational education and training system in Finland is now largely founded on competence based vocational qualifications, and the Netherlands have developed a specifically Dutch version of the NVQ system. Many European countries also offer an opportunity to establish equivalence between informally acquired competences and competences obtained via formal pathways (cf. BJØRNÅVOLD 2001). Switzerland, for example, reformed its Vocational Training Act (BBG) in 2004 to enshrine the recognition of informal learning in law (cf. GELDERMANN et al. 2009).

The European Commission is supporting these processes by putting mechanisms in place for European cooperation in the field of education and training, such as via the joint "Education and Training 2010" work programme (cf. Council of the European Communities 2002) or within the scope of the Copenhagen process. The agreement on the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), which is serving as a vehicle for the development of compatible national models, and the activities in the context of the European Credit Transfer System for Vocational Education and Training (ECVET, cf. BMBF 2008) represent important developments for the validation of the results of informal learning. Both are consistently aligned to learning outcomes rather than formal qualifications, independent of where and how learning outcomes were achieved. As a consequence of this paradigm shift from input to outcome orientation, the focus of interest is now on which skills, competences and knowledge a person has actually acquired rather than on which learning content has been imparted. This will clearly strengthen the significance of learning outside the formal systems on a pan-European basis and will hopefully make it easier to use competences obtained in this way 1

The European funding programmes are a central instrument in the implementation and piloting of the educational policy aims of the EU Commission. As early as 2004, the same year in which the Common European Principles for the identification and validation of non-formal and informal learning (Council of the European Union 2004) were published, the LEONARDO DA VINCI Vocational Training Programme declared the "evaluation of learning" to be a priority right across Europe (cf. current development in CEDEFOP 2009). As a consequence, a large number of transnational projects commenced work. There is only space to mention a few of these here.

The project and product portal at http://www.adam-europe.eu/ provides a comprehensive summary and information on results of LEONARDO DA VINCI funded projects throughout Europe. Entering the key search words "recognition, transparency, certification" or conducting an individual text search using the term "informal learning" will bring up a plethora of concepts, materials and practical experiences.

On the situation in Germany

In Germany, "informal learning" has for some considerable time not been accorded the same degree of social and academic research attention as in other countries despite the fact that the so-called Faure Reports of 1972 and the results of the research results from Livingstone in 1999 indicated that around 70 percent of all adult learning processes do not take place within the formal educational system (cf. DOHMEN 2001). Notwithstanding this, an increasing number of studies in Germany which explicitly deal with informal learning has been recorded (cf. OVERWIEN 2009). The decisions and resolutions of the Federal Bund-Länder-Commission for educational planning and research promotion indicate that a rethink is slowly beginning and that greater focus is being placed informal and non-formal learning processes (cf. BLK 2004). For a considerable period of time, the situation in Germany was characterised by the fact that recognition and acceptance was primarily given to qualifications acquired within the formal educational system, a circumstance which still appertains in some areas today. Formal qualifications and certificates have traditionally been accorded an overwhelming degree of significance on the labour market with regard to securing individual employability skills and within collective wage bargaining and remuneration systems (cf. FRANK et al. 2003). Since this system has always enjoyed a high level of acceptance in Germany, very little pressure existed in the past to pursue broadly based identification and recognition of informally acquired competences. This is, however, beginning to alter in the wake of the far-reaching changes taking place in technology, society and within trade and industry and in the attendant rise in significance of lifelong learning. Furthermore, the developments towards a European Education Area are not the least of the factors in generating a necessity to act.

The Country Reports of the OECD confirm the existence of the urgent need for action in Germany. The reports indicate that the alignment of the German educational system towards formal qualifications renders it highly selective, meaning that certain groups of persons are disadvantaged (cf. OECD 2008). This makes educational participation insufficient in overall terms, and participation by those from a migrant background in particular being unsatisfactory. A further point of criticism levelled by the OECD is that the quota of graduates is too low due to the fact that those with occupational experience but not in possession of a higher secondary school leaving certificate have not hitherto had an opportunity to access higher education.

Notwithstanding this, the declared educational policy aim both in Europe and in Germany over the course of recent times has been to increase permeability within the educational and employment systems. The BIBB initiative ANKOM (a German acronym for "Accreditation of Vocational Competences to Higher Education") represents one specific application context in this regard (cf. FREITAG 2008). The recognition of informal learning outcomes also provides a major opportunity for many disadvantaged groups, such as the four million German inhabitants who are unable to read or write properly. Within this context, "permeability" relates to initial access to formal education in the first place rather than referring to the transition to another sector of education. Such access has up until now been made difficult for many if they are not in possession of any certificates attesting to their competences (cf. NEß 2009).

No regulations exist in Germany as yet for the official recognition of informally acquired competences. Approaches which have been undertaken hitherto have largely been directed at areas below the level of regulatory policy (cf. GELDERMANN et al. 2009). Formal recognition would include regulatory policy stipulations and would take place in conjunction with entitlements to access education and entitlements within the employment system. Notwithstanding this, various in-company and collective wage agreements are in place which accord due consideration to informal competences, and there is a large number of initiatives and programmes with varying focuses which are dedicated to the topic.

Extensive work is currently ongoing on the German Qualifications Framework (known by its German abbreviation of DQR) as already mentioned. The aim is for the DQR to be developed in conjunction with the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) and for an evaluation to take place by 2012 (cf. Arbeitskreis Deutscher Qualifikationsrahmen 2009). The plan is to align all existing - formal - qualifications within the German educational system to various reference and competence levels within the DQR. At the same time, however, the objective is for informally acquired competences to inform the process. The precise degree to which the DQR will be able to take account of the recognition of informally acquired competences whilst continuing to uphold the principle of the regulated occupation remains, nevertheless, unclear (cf. BMBF 2008a).

Synergies between German and European initiatives

National and European developments with regard to the identification of informally acquired competences are interwoven in a wide variety of ways. Any attempt to subject them to separate observation would entail ignoring valuable opportunities for synergy. As well as considering policy developments, it is also worth consulting the activities and results of European projects for one's own work. Let us state a few examples at this point.

THE INDIVIDUAL LEVEL: PREPARING COMPETENCES FOR THE LABOUR MARKET

Numerous educational and competence passports have been developed within various regional and national contexts since the mid 1990's. One prominent example of these is the German "ProfilPass", which enables an individual to address his or her own occupational action and competences. The aim is to provide a motivation to pursue lifelong learning by using the ProfilPass for such purposes as assistance with re-entry to working life or as preparation for vocational reorientation (cf. GELDERMANN et al. 2009, pp. 90 f.).

The EU Commission adopted a somewhat different approach with the introduction of the Europass Portfolio in 2005 (www.europass-info.de). The main aim of the EuroPass was to increase the comparability of learning and employment experiences by acting as a set of instruments coordinated at a pan-European level. As well as formal qualifications, the EuroPass Curriculum Vitae, for example, also maps occupational experience and language, social and other competences in a standardised form (cf. Figure 1). Results from the work conducted with the Profilpass can be used to inform the EuroPass Curriculum Vitae without difficulty. In addition to this, an online tool specifically aimed at young people has been developed within the scope of the LEONARDO project "europass +"(www.europasspluss.de). This supports the preparation of informally acquired competences for the EuroPass Curriculum Vitae. Whereas the ProfilPass is an instrument which mainly supports individual processes of reflection, the EuroPass Curriculum Vitae features a stronger external alignment towards utilisation on the labour market e.g. within the scope of job applications.

Figure 1: Extract from the Europass Curriculum Vitae - example

THE OPERATIONAL LEVEL: USING COMPETENCES FOR THE COMPANY

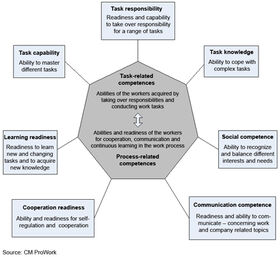

Learning at the work place and the competences thus acquired have increasingly formed an object of observation and research in recent years (cf. DEHNBOSTEL/ELSHOLZ 2007). The identification of staff competences and the drawing up of competence profiles are also playing a greater role for companies (cf. Arbeitsgemeinschaft QUEM 2005). The European partners involved in CM ProWork - "Competence management in Production Work. Identification, development and evaluation of non-formal learning in the M+E production sector" - based their work on specific industrial production work processes (www.cmprowork.de). The aim of this LEONARDO project was to survey the competences of workers independently of their formal qualifications in order to make these useful for company competence management. The result was a software tool which assists in identifying staff competences in a task related manner. The project's starting assumption was that the production sector in particular contains a wide variety of informal learning and experience processes and specifically involves an especially large number of semi-skilled, retrained and unskilled workers. Although these workers are formally deemed to be low skilled, they are in possession of considerable specialist and interdisciplinary competences. As a consequence of the transnational discussions which were held, the "Task-related competences" which had formed the initial object of focus (Task Knowledge, Task Capability and Task Responsibility) were supplemented by "Process-related competences" in the form of Learning Readiness, Cooperation Readiness, Social Competence and Communication Competence (cf. Figure 2). These competences were identified by means of a task inventory containing around one hundred standardised work tasks from the industrial production sector. The CM-ProWork software thus enables management in production companies to use all available resources in strategic corporate planning by adopting a learning outcomes oriented approach. This is also of benefit to the employees, especially to those who do not have any formal qualifications.

Figure 2: Task-related and process-related competences

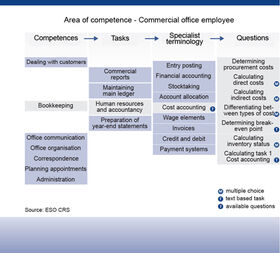

Figure 3: A system for the configuration of competence tests taking a commercial office employee as an example

THE FORMAL LEVEL: CERTIFYING COMPETENCES

One procedure firmly established in Germany for the formal confirmation of existing competences is the so called "Externenprüfung" (external examination). This was introduced at the end of the 1960's for adults with many years of occupational experience. It permits persons who have gained experience to be admitted to the final examination of an initial vocational education (§ 45, Paragraph 2 of the Vocational Training Act, BBiG, and § 37, Paragraph. 2 of the Crafts and Trades Regulation Code, HWO). According to the 2008 Report on Vocational Education and Training, external examinations made up 7.2 percent of all final examinations (not including craft trades) (cf. BMBF 2008b). What opportunities for certification are there, however, when a person has acquired competences from different (formal) training occupations? Or when the level of competence is higher than that of initial vocational training? One question which is increasingly characterising German debate and to which the European projects will also need to find a response is the issue of objective competence assessment, and ideally even the certification of such competence. The partners in the LEONARDO innovation transfer project ESO CRS - "Development of a scalable internet-based solution for the evaluation, the assessment and the recognition of knowledge and competences that have been acquired through non-formal and informal learning" - (www.cemes.eu) developed a system which enables competences to be made visible by combining and conducting individual examinations (cf. Figure 3). A complex online tool was designed for this purpose by bringing together two prize-winning LEONARDO pilot projects. An attempt was undertaken to compile a complete set of competence descriptions, of tasks arising at the workplace and of relevant specialist terminology for commercial office work, for general management tasks and for mechatronics and electronics technicians. Each of these terminology items is backed up with examination questions. The catalogue of questions currently comprises around 1,700 examination questions (status August 2009), and the aim is that examiners continue to expand this number. One major benefit of this instrument is the fact that competences and tasks are freely combinable for specific examination purposes, whether this be within the context of human resources development, promotion, transfer or recruitment. The training centre operated by the Cottbus Chamber of Industry and Commerce is already involved in the project as an examination centre, and the plan is for more centres to follow. The plan then is to use the online tool to issue Chamber of Industry and Commerce certificates on existing competences from 2010 onwards without any necessity to attend a course beforehand.

Daring to look beyond our own horizons and reaping the benefits of doing so

As we have shown, dealing with informally acquired competences exhibits a wide range of facets. The initial focus is on the identification and documentation of such competences. The second stage involves issues relating to certification and recognition. The approaches and application contexts which have been described for Germany make it clear that significant developments are occurring in this field. Particularly the activities being pursued in conjunction with the EQF and the DQR are assisting in explicitly focussing attention on competences acquired outside formal educational courses. Germany, however, continues to lack an appropriate infrastructure for the identification and recognition of these competences. For instance, better support structures and more detailed information on available opportunities in some areas, such as the external examination, are needed. As far as institutes of higher education are concerned, the abandonment of classical entry conditions would enable us to tap into an important area of potential if access to higher education was open to those with occupational experience. And it could be made easier for people with lower levels of qualification or even no qualifications at all to gain access to or remain in employment if successful individual solutions are made permanent.

The European projects are delivering impetuses for German VET stakeholders in many regards. There is transnational experience with competence descriptions for specific occupations or various occupational fields, the practical feasibility of solutions have been tested in systems featuring varying structures and conventions and, thanks to a clear commitment to learning outcomes orientation, project results are up-to-date and capable of future application. The present paper is intended to stimulate greater consultation of the experiences and results of European projects, including within the scope of national activities relating to the identification of informal learning processes, whether these take place at a policymaking level or within practice.

Literature

- ARBEITSGEMEINSCHAFT QUEM (Ed.): Kompetenzmessung im Unternehmen.

Lernkultur- und Kompetenzanalysen im betrieblichen Umfeld. Münster 2005 - ARBEITSKREIS DEUTSCHER QUALIFIKATIONSRAHMEN: Diskussionsvorschlag

eines Deutschen Qualifikationsrahmens für lebenslanges Lernen, February 2009 - URL: www.deutscherqualifikationsrahmen.de (Status:12. 10. 2009) - BJØRNÅVOLD, J.: Lernen sichtbar machen. Ermittlung, Bewertung und Anerkennung nicht formal erworbener Kompetenzen: Trends in Europa.

Luxemburg 2001 - BLK: Strategien für Lebenslanges Lernen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Issue 115, Bonn 2004

- BMBF: Stand der Anerkennung non-formalen und informellen Lernens

in Deutschland - im Rahmen der OECD Aktivität "Recognition of non-formal and informal learning". Bonn/Berlin 2008a - MBF (Ed.): Berufsbildungsbericht 2008. Berlin/Bonn 2008b

- CEDEFOP - European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training:

European guidelines for validating non-formal and informal learning. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg 2009 - COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION: Detailed work programme on the follow-up of the objectives of Education and training systems in Europe. Published in the Official Journal of the European Communities on 14. 06. 2002 (Notice No.: 2002/C 142/01)

- COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION: Draft Conclusions of the Council and of the representatives of the Governments of the Member States meeting within the Council on Common European Principles for the identification and validation of non-formal and informal learning, Brussels 2004 - URL: http://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/2010/doc/validation2004_en.pdf (Status: 12. 10. 2009)

- DEHNBOSTEL, P.; ELSHOLZ, U.: Lern- und kompetenzförderliche

Arbeitsgestaltung. In: Dehnbostel, P.; Elsholz, U.; Gillen, J. (Eds.):

Kompetenzerwerb in der Arbeit. Perspektiven arbeitnehmerorientierter

Weiterbildung. Berlin 2007, pp. 35 ff. - DOHMEN, G.: Das informelle Lernen. Bonn 2001

- ERTL, H.: Anerkennung beruflicher Qualifikationen im Rahmen des Systems der National Vocational Qualifications. In: Straka, G. A. (Ed.): Zertifizierung non-formell und informell erworbener beruflicher Kompetenzen. Münster 2003, pp. 69-81

- FRANK, I.; GUTSCHOW, K.; MÜNCHHAUSEN, G.: Vom Meistern des Lebens

- Dokumentation und Anerkennung informell erworbener Kompetenzen.

In: BWP 32 (2003) 4, pp. 16-20 - FRANK, I.; GUTSCHOW, K.; MÜNCHHAUSEN, G.: Verfahren zur Dokumentation

und Anerkennung im Spannungsfeld von individuellen, betrieblichen und gesellschaftlichen Anforderungen. Bielefeld 2005 - FREITAG, W.: Gleiche Chance für alle. Anrechnung beruflich erworbener

Kompetenzen. In: PADUA 3 (2008) 16, pp. 18-20

URL: http://ankom.his.de/aktuelles/upload/PADUA1-08 S18-20 printres.pdf (Status 12. 10. 2009) - GELDERMANN, B.; SEIDEL, S.; SEVERING, E.: Rahmenbedingungen zur

Anerkennung informell erworbener Kompetenzen. Bielefeld 2009 - NEß, H.: Bedingungen für Vergleichsstandards einer Validierung informellen

Lernens in Bildung und Beruf. In: Brodowski, M. et al. (Eds.): Informelles Lernen und Bildung für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung. Opladen 2009, pp. 43-55 - OECD (Ed.): A profile of immigrant populations in the 21st century. Data from OECD countries. Paris 2008

- OECD: Education at a glance Blick 2008 - URL: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/16/8/41261663.pdf (Status: 12. 10. 2009)

- OVERWIEN, B.: Informelles Lernen. Definitionen und Forschungsansätze.

In: Brodowski M. et al. (Eds.): Informelles Lernen und Bildung für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung. Opladen 2009, pp. 23-34

footnotes

-

1

Information on all developments within the European Educational Area supported by the EU Commission is available at http://ec.europa.eu/education/index_en.htm.

Translation from the German original "Erfassung von informell erworbenen Kompetenzen. Impulse aus europäischen Projekten nutzen" (published in BWP 6/2009)