Dual courses of study from the perspective of the enterprises-a practical model of success through selection of the best

Franziska Kupfer

With the dual courses of study, a promising training model has taken root at the interface between vocational and university education. The number of courses offered by the universities and the demand on the part of enterprises and students has increased steadily in recent years. There are hardly any larger enterprises not offering dual study places. But why is it that companies engage in dual courses of study and what makes this study model so successful? In November 2012, the BIBB conducted an online survey among 280 enterprises that were participating in dual courses of study at universities of applied sciences. The results presented in this article show that dual courses of study are attractive recruiting tools for the enterprises although their quality potential may not yet have been exhausted.

Most dual study programmes are offered by universities of applied sciences

The first dual study programmes were introduced at the beginning of the 1970s at the colleges of advanced vocational studies in Baden-Württemberg. The concept was gradually adopted by other federal states and educational institutions of the tertiary sector, particularly the universities of applied sciences (cf. Graf 2012, p. 50).

The BIBB's AusbildungPlus database as of the last reporting date in April 2012 lists:

- 537 dual courses of study at universities of applied sciences (FHs),

- 206 courses at other higher education establishments (of which 195 at the Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University),

- 137 courses at colleges of advanced vocational studies and

- 30 courses offered at universities. (cf. Goeser 2013, p. 24) 1

Thus the universities of applied sciences offer the greatest number of dual courses of study, namely 60 per cent of the total. However, this figure is put into perspective when we compare the study places offered at universities of applied sciences, which amounted to only 41 per cent of the total of 64,093 places offered in the year 2012 (cf. Goeser 2013, p. 45). This discrepancy is the consequence of a distinct feature of the dual studies at universities of applied sciences, which do not always dispose of courses they have directly designed as dual courses. In such cases the dual students are enrolled in the "classical" bachelor degree programmes and complete their vocational education or on-the-job activity, for example, during a year of workplace experience preceding the beginning of their studies and during later lecture-free periods.

Design of dual courses at universities of applied sciences from the perspective of enterprises

The BIBB online survey was directed at companies cooperating in dual courses of study at universities of applied sciences that are included in the AusbildungPlus database.2 Not consulted were companies cooperating in dual courses of study at colleges of advanced vocational studies, the Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University or the universities, since the courses are in part quite different in structure, organisation and cooperation structures.

More than two-thirds of the enterprises polled were large enterprises employing 250 or more people and 40 per cent of the responding enterprises even had 1,000 or more employees (see table).

Although it is known that a disproportionate number of large enterprises also engage in dual vocational education and training (see BIBB 2013, Table A4.11.2-4), this effect may be even greater with regard to participation in dual courses of study. Accepting dual programme students requires not only a considerable coordination and training effort but also a commensurate financial commitment. Both are more feasible for large enterprises. The companies surveyed offer their dual courses of study primarily in the fields of engineering (66%) and economics (61%). Nearly one-third of the companies also train dual programme students in computer sciences (30%).

Design of the enterprise survey

| Design of the enterprise survey | acquisition of current findings on the design of dual courses of study and especially the implementation of the vocational training portion or the practical phases in the enterprises |

| Population |

1,387 companies cooperating in dual courses of study at universities of applied sciences included in the AusbildungPlus database

|

| Target persons |

contact persons identified by name in the AusbildungPlus database

|

| Responses | 280 completed interviews (yield: 20 per cent) |

| Survey method |

online survey with standardised questionnaire

|

| Survey period | November 2012 |

Dual courses of study can be differentiated in terms of their structure and their addressees. Dual courses of study integrating classroom and workplace training are addressed to young people with university entrance qualifications and serve the purpose of initial vocational education and training (cf. Mucke 2003, p. 4). Nearly three quarters of the responding enterprises offer dual courses of study in the training-integrative form (74%). This means that they combine academic studies with for the most part condensed training in a recognised training occupation. Graduates take two exams: In addition to a Bachelor's degree, they also acquire a certificate in what is usually a dual training occupation. But only two-thirds (66%) of the enterprises that offer so-called training-integrative courses of study still conclude an apprenticeship contract in compliance with BBiG/HwO with their dual students. 17 per cent of the enterprises use only the so-called extern examination (in accordance with § 45 paragraph 2 of the BBiG or § 37 paragraph 2 of the HwO); another 16 per cent of the companies surveyed use both.

Exactly half (50%) of the companies surveyed offer practice-integrating dual courses of study combining academic studies with extended practical phases in the enterprises. Nearly one-third of the enterprises (29%) indicated that they also offered on-the-job continuing education opportunities for their already-trained skilled personnel

Enterprises appreciate the practical relevance of dual courses of study

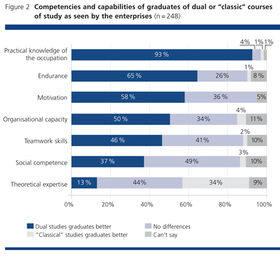

But for what reasons do enterprises engage in dual courses of study? Almost all respondents (97%) felt that the practical training was important for their enterprises (response categories: totally agree, more or less agree). 93 per cent of the enterprises indicated that the best young talent could be acquired through dual courses of study (see Fig. 1). Concomitant with this is the assertion that dual courses of study are more attractive for young people than the classical initial vocational education and training in the dual system (76%). Other reasons for participation in dual courses of study are the improvement of the company image (69%) and the expansion of the cooperative relationships with the universities of applied sciences (65%). The majority of the enterprises (67%) more or less disagreed or strongly disagreed that the possibility of influencing the curriculum was a consideration. This refutes a frequently voiced prejudice to the effect that enterprises might excessively influence the content of university courses.

In addition to the abovementioned reasons given for participation in dual courses of study, it is also required that a suitable number of qualified candidates are available. Quite often these candidates have to go through extensive selection procedures in the enterprises. The enterprises surveyed reported an average of 33 applications per dual studies vacancy (the median is 20 applicants). The large enterprises have the highest number of applicants. In addition, study places in business sciences and engineering are more in demand than, for example, in computer sciences.

Competence edge for graduates of dual courses of study

As Figure 1 illustrates, companies expect dual students to have a skills advantage. The vast majority of companies (91%) noticed such differences.

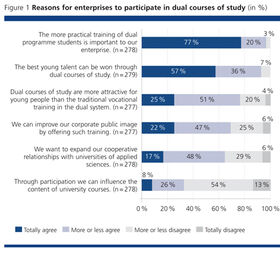

But how do dual students differ from graduates of "classical" courses of study in terms of skills and abilities? The overwhelming majority of the respondent enterprises (93%) replied that graduates of dual courses of study had a more pronounced practical knowledge of their occupations than graduates of "classical" courses of study (see Fig. 2). The inverse is true with regard to theoretical expertise: Here the enterprises are of the opinion that the graduates of classical courses do better than those of dual courses of study. However, the perceived differences were not as pronounced as the differences in practical knowledge. As many as 44 per cent of the enterprises indicated that they could detect no difference between the graduate groups as far as theoretical expertise was concerned. While these assessments were obviously due to the individual profiles of the dual or "classical" courses of study, the observed differences in the field of social skills and personality traits cannot be explained solely in terms of the course of studies completed. More than half of the enterprises, for example, were of the opinion that dual studies graduates were more robust and more motivated to perform than the classical students. In terms of social competence, 37 per cent of the enterprises see specialised personnel with dual studies degrees in the advantage, although almost half the respondents could see no differences between the groups of graduates in this respect.

Low dropout rates and high retention rates

One of the main reasons why dual courses of study are considered to be models of success is that they usually have quite low dropout rates (cf. Berthold et al. 2009, p. 44). The companies surveyed confirmed this trend and gave the average dropout rate as 6.9 per cent (the median is 5%).

The reasons for this according to the companies are (multiple answers possible):

- wrong career choice (64%),

- excessive study requirements (55%),

- personal reasons of students (48%) such as illness or relocation,

- excessive workload (45%),

- lack of motivation on the part of students (23%), and conflicts in the enterprise (6%).

A similar positive image emerges when we consider the rates of retention of dual studies graduates by the enterprises. 61 per cent of the companies surveyed indicated that they retained all graduates after they completed their studies. On average, 89 per cent of successful students are given jobs after completing a dual course of study. The arguments against retention that the enterprises have had at some time are (multiple answers possible):

- lack of social skills (55%),

- poor performance (55%),

- deterioration of the economic situation of the enterprise (52%),

- poor academic performance of the graduates (52%),

- no suitable position available (26%) or

- the graduates themselves did not wish to be retained (15%).

The high retention rates can also be seen in conjunction with the limited opportunities students have to switch to a different enterprise after graduation. Increasingly, the dual students' contracts contain what are known as commitment clauses requiring them to stay with the enterprise for a certain period after completing their studies (often 2-3 years). Of the enterprises surveyed, 45 per cent use such commitment clauses, usually associated with claims for repayment in the event of non-compliance.

Integration and transfer of subject matter-task of the dual students?

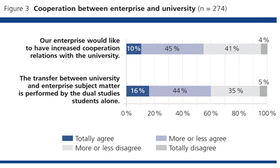

It is attractive for the enterprises to train their future managerial and technical personnel in dual courses of study. The competence advantage of dual studies graduates described above as well as the low dropout and high retention rates are further justification for calling dual courses of study a success story. But what are the reasons for this success? It would be reasonable to expect to find the recipe for success in the particular construction of such study opportunities in which two mutually beneficial learning venues dovetail. But most of the dual courses of study are far from claiming to comprise a whole in terms of content or curriculum. Often there are clearly delimited responsibilities: The university is responsible for imparting academic knowledge, while the enterprises are responsible for imparting vocational and operational competencies and skills (Kupfer et al. 2012, p. 17). Thus in the present survey 91 per cent of the enterprises agreed with the statement that the enterprises were solely responsible for the vocational training or the practical vocational activity of the students (response categories: totally agree; more or less agree). The inverse statement that the higher education establishments were solely responsible for the academic content was confirmed by 79 per cent of the companies polled. Both learning venues operate largely autonomously and have little contact and interchange except on organizational questions. However, the survey also shows that the enterprises wish to have greater cooperation with the higher education establishments. 55 per cent of the companies confirmed this statement (see Fig. 3). Mutual understanding between the two learning venues could be promoted and the quality of teaching and practice could be enhanced through more intensive cooperation, including cooperation in terms of content.

Up to now it is mostly the students as the "integrative entity in these courses of study" who have performed the transfer between the learning venues (Holtkamp 1996, p. 12). This thesis too was confirmed by the majority of the companies polled (60%). Thus a large part of the responsibility for the success of dual study models lies on the shoulders of the students.

Against this background, it is understandable that 97 per cent of the enterprises polled attach importance to the "careful selection of future dual students" and describe this as the core quality assurance instrument. The enterprises conduct elaborate selection procedures (mostly multi-day assessment centres) in order to hire the most suitable applicants. This selection of the best is not a random element, but is itself "a part of the concept of dual courses of study" (Holtkamp 1996, p. 13).

Quality not quantity-a way to promote quality and attractiveness in dual courses of study

Dual courses of study score points through their practical relevance and are an important instrument for recruiting skilled manpower, especially for large enterprises. Their positive image and success is due above all to the enterprise practice of selecting the best. High-performing young people are a main warrant for success. For this reason, efforts to significantly expand the availability of dual courses of study seem to be unpromising. A number of companies already have trouble finding suitable applicants for their demanding dual programmes of study. Moreover, most of the enterprises are making no effort to expand their commitment to dual courses of study any further. For despite the advantages mentioned, only about a third (35%) of the enterprises polled are currently planning to admit more dual students in the next five years. Over half (52%) of the enterprises would like to go on offering dual study places at the current level.

In the event that in the future dual courses of study will be supposed to address target groups other than the best performing and most highly motivated school leavers, the students must not be left bearing sole responsibility for linking and transferring university and enterprise subject matter. Instead, vocational training and/or practical work phases should already be linked better with academic content at the curricular level.

Since training-integrative dual courses of study have so far been mainly the domain of the universities of applied sciences, those universities could use this as a unique selling point and initially enhance primarily the quality of what they offer. It is expedient in this connection to work more closely together with the institutions of vocational education and training like the appropriate Chambers. Within the framework of such cooperation, high-quality integrated study models could be developed and thus the potential for the dovetailing of vocational and academic education could be better exploited. This would also counteract the overly theoretical nature of higher education courses, and vocational education and training could profit from improved transfer of new technologies into the enterprises as well. The initial vocational education and training should be completed within the framework of a regular apprenticeship contract to highlight the recognition and appreciation of the vocational training part of the dual course of study and to take advantage of a training relationship that is regulated by legal guidelines.

Both the vocational and the academic education would benefit from this closing of ranks and profit from mutual recognition of learning achievements acquired. Ultimately this could also ease the burden on dual students and make dual courses of study accessible to a wider target group.

Literature

BERTHOLD, C. et al.: Demographischer Wandel und Hochschulen. Der Ausbau des Dualen Studiums als Antwort auf den Fachkräftemangel. Gütersloh 2009

BIBB (eds.): Data Report of the 2012 Vocational Education and Training Report. Information and analyses on the development of vocational education and training. Bonn

2012 - URL: http://datenreport.bibb.de/ (accessed on 12 June 2013)

GOESER, J. et al.: AusbildungPlus in Zahlen. Trends und Analysen

2012. Bonn 2013 - URL: www.ausbildungplus.de/files/AusbildungPlus_in_Zahlen_2012.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2013)

GRAF, L.: Wachstum in der Nische. Mit dualen Studiengängen entstehen Hybride von Berufs- und Hochschulbildung. In: WZB Mitteilungen 138 (2012), pp. 49-52

HOLTKAMP, R.: Duale Studienangebote der Fachhochschulen. Hannover

1996

KUPFER, F. et al.: Analyse und Systematisierung dualer Studiengänge an Hochschulen. Zwischenbericht. Bonn 2012 - URL: https://www2.bibb.de/tools/fodb/pdf/zw_33302.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2013)

MUCKE, K.: Duale Studiengänge an Fachhochschulen. Bielefeld 2003

FRANZISKA KUPFER,

Research associate in the "VET Personnel, Digital Media, Distance Learning" Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 4/2013): Martin Stuart Kelsey, Global Sprachteam Berlin

-

1

The underlying data is based on voluntary information of the educational establishments and does not correspond to any census of the dual programmes of study in Germany.

-

2

Although universities of applied sciences ("Fachhochschulen") are increasingly given other names, such as "Hochschule" or "Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften" or the corresponding English names, they are still the same type of university, pursuing teaching and research on a scientific basis with an application-oriented focus. In the interest of readability the term university of applied sciences will be used in the present article as a synonym for all institutions of this type.