Advanced training versus higher education qualifications - a comparison of incomes

Anja Hall

In Germany, upgrading training can open up pathways to company positions which in other countries are exclusively reserved for higher education graduates. The question is whether this is reflected in comparable remuneration. The latest OECD comparison provides very little cause for hope in this regard. Nevertheless, the analysis fails to accord consideration to factors which draw a differentiated picture. This is presented here on the basis of the results of a current employee survey.

The OECD Comparison - Not comparing like with like?

According to the OECD (2013), in the year 2011 male employees in Germany with a tertiary qualification at ISCED level 5B 1(where upgrading training courses are aligned) earned 127 percent of the employment income of their age group with an upper secondary qualification. The income advantage for women was only 115 percent. Male workers with an academic qualification at ISCED level 5A earn an average of 174 percent women 166 percent) of the income of their corresponding age group with a vocational qualification (cf. OECD 2013, p. 103).

Differences in income associated with a higher level of prior school learning or occupational specialism are, however, not taken into account in this comparison. Unlike higher education, access to dual vocational education and training is not formally linked with a certain school leaving qualification. A particular strength of the German dual system is considered to be its broad spectrum of training occupations with varying income opportunities that takes account of the different prior learning of school leavers. Regulated upgrading training also normally "only" requires completion of vocational education and training and relevant occupational experience, mostly of several years' duration. This means that there are no school-based prerequisites. For this reason, such advanced training courses particularly open up career opportunities for persons not in possession of a higher education entrance qualification to reach occupational positions that, for example, in other countries are exclusively available to employees with academic qualifications. The most significant advanced training occupations in quantitative terms include master craftsmen, technicians, business economists, certified senior clerks and specialist commercial clerks.2

On the basis of a representative employee survey from the year 2012 (cf. box), an investigation is carried out into the extent to which persons who have successfully completed upgrading training are able to gain access to income opportunities comparable to those enjoyed by who have graduated from Universities of Applied Sciences and institutes of higher education. Persons with dual or school-based VET serve as a comparison group.

Database

The BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey is a telephone-based, computer-aided representative survey of 20,000 persons in active employment in Germany jointly conducted by the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB) and the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA). The data was collected between October 2011 and March 2012 by TNS Infratest Sozialforschung in Munich. The statistical population comprises persons in active employment aged from 15 years (not including trainees). Employment is considered to be regular work activity of at least ten hours per week for which payment is received ("core workers"). More information on the concept, methodology and results of the survey is available at www.bibb.de/arbeit-im-wandel.

How high are the income advantages of employees with higher education degrees and advanced training qualifications?

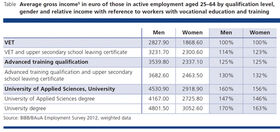

According to the data of the BIBB/BauA Employee Survey, male higher education graduates earn around 160 percent of the income of employees who have completed vocational education and training. The corresponding figure for female graduates is 156 percent (see Table). Compared to this, the relative income advantage for employees who have completed advanced training (master craftsman, technician, business economist, certified senior clerk or specialist commercial clerk) is around 125 percent for men and women 3(cf. Table). Nevertheless, only 23.1 percent and 38.1 percent respectively of men and women with an advanced training qualification hold a higher education entrance qualification. The proportion of master craftsmen who have completed only a lower secondary school leaving qualification is as high as around 40 percent.

Male workers with the upper secondary school leaving certificate, vocational education and training and an advanced training qualification achieve around 130 percent of the gross income of all male employees with VET. The corresponding figure for women is 132%. Upgrading training and relevant prior school learning reduces the income gap experienced by workers with vocational education and training as opposed to higher education graduates by approximately a half. 4

Table

Differences in income according to specialism

The range between low and high earners is significantly larger for employees with a higher education degree than for those with an advanced training qualification. One of the reasons for this is the fact that employees with a university degree earn appreciably more than graduates of Universities of Applied Sciences. There are also major differences depending on the specialism of the higher education degree. In addition to this, upgrading training is more likely to take place in commercial occupations in which the incomes achieved are generally lower than in the service occupations typically adopted by higher education graduates. It is perfectly possible for a male skilled worker who has completed advanced training as a specialist commercial clerk or business economist to achieve a similar monthly gross income to a graduate in business administration from a University of Applied Sciences (€4,150 as opposed to €4,680). Compared to this, those who have achieved a master craftsman qualification earn significantly less (€3,331). Despite the higher average income of graduate employees, a study conducted by the German Institute for Economic Research suggests that the shorter phase of training and lower investment costs mean that persons with upgrading training produce a slightly higher educational return than higher education graduates (cf. ANGER/PLÜNNECKE/SCHMIDT 2010).6

Conclusion

It is a well known fact that higher education opens up career and income opportunities. The same also applies to "career oriented" persons within the dual system of vocational education and training, who are able to achieve significance increases in come by subsequently pursuing advanced training. Upgrading training offers the chance of career advancement to those with and without a higher education entrance qualification. The particular strength of the dual system is that it provides a broad spectrum of training occupations with various levels of requirements and also offers the chance of a good income to young people not in possession of a higher education entrance qualification. For this reason, an income comparison between those with vocational and academic qualifications should be based on broadly similar starting conditions and should take the prior school learning level and the occupational specialism into account.

Literature

ANGER, C.; PLÜNNECKE, C.; SCHMIDT, J.: Bildungsrenditen in Deutschland. Einflussfaktoren, politische Optionen und ökonomische Effekte. Köln 2010

BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR BILDUNG UND FORSCHUNG [FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND RESEARCH (Ed.): Aufstieg durch berufliche Fortbildung. [Advancement through advanced vocational training] German Background Report to the OECD Study "Skills beyond School". Bonn 2011

OECD: Education at a glance: OECD Indicators. Paris 2013

ROHRBACH-SCHMIDT, D.; HALL, A.: BIBB/BAuA-Erwerbstätigenbefragung 2012 [2012 Employee Survey by the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training, BIBB and the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, BAuA]

BIBB-FDZ [BIBB Research Data Centre] Data and Methodology Report No. 1/2013

DR. ANJA HALL

Research associate in the "Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment" Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 5/2013): Martin Stuart Kelsey, Global Sprachteam Berlin

-

1

International Standard Classification of Education (see http://metadaten.bibb.de/).

-

2

Advanced training occupations can be established at federal, chamber or federal state level (trade and technical school for technicians). Within the German educational system, upgrading training is considered to be part of formal advanced vocational training, which unlike updating training increases the formal qualification level. Aspects such as conditions for admission and the examination procedure are stipulated via relevant advanced training regulations (cf. Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BMBF 2011).

-

3

The ability of women with an advanced training qualification to achieve a comparable income advantage to men is connected with the fact that school-based training courses in the fields of healthcare and education are aligned to the level of vocational education and training and not to ISCED level 5B as in the OECD studies (cf. OECD 2013 Annex 3, p. 37). The reason for the OECD alignment is the international comparability of such qualifications.

-

4

Working time has thus far not been taken into account in the analysis based on the OECD figures (cf. OECD 2013 Annex 3, p. 57). Differences in this regard are particularly to be expected for women due to the fact that women with vocational education and training (50%) are more likely to work on a part-time basis (fewer than 35 hours per week) than women with an advanced training qualification (39%) or women with a higher education degree (45%). The relative gains made by female graduates and women with an advanced training qualification working full-time therefore fall to 145 percent (instead of 156 percent) and 116 percent (instead of 125 percent) respectively.

The figures for men remain virtually unchanged due to the lower frequency of part-time work. -

5

Missing income data and outliers were imputed or replaced on the basis of an MNAR dropout mechanism

(cf. ROHRBACH-SCHMIDT/HALL 2013). -

6

Educational return is the annual interest percentage by which lost income during training is paid back by a higher income after training. For graduates compared to persons without VET, the figure is 7.5 percent. For persons with advanced training, the educational return is 8.3 percent (cf. ANGER et al. 2010).