Orientation in the vocational training jungle

Andreas Krewerth, Verena Eberhard, Julia Gei

What draws young people’s attention to training occupations and training places?In their search for training occupations, young people come across numerous offers and market players intent on pointing them in particular directions. In the face of this diversity, the question that arises is how young people experience the phase of career choice and job-hunting, and what forms of provision they find most helpful: are personal contacts and conversations as high a priority as ever, or is the Internet the primary means of attracting young people’s attention? And do information-finding and searching strategies vary with selected socio-demographic attributes? Current empirical findings on these questions are supplied by the 2012 Vocational Training Applicant Survey conducted by the Federal Employment Agency (BA) and BIBB.

Choice of occupation under changed conditions

The process of choosing an occupation represents a complex development task for young people. They need to find an occupation which matches their abilities and interests whilst also investigating what training place opportunities are available to them on the basis of their prior leaning (e.g. level of education) and what application strategies they can use to realise these. All of these stages will determine both future everyday working routine and the social attributions young people will face as members of an occupation (cf. Eberhard/Krewerth/Ulrich 2010). This complex tasks cannot normally be completed in a purely rational manner. For this reason, young people also allow themselves to be guided by the feelings and recommendations of persons whom they trust (cf. Neuenschwander/Hartmann 2011).

Career and training place selection is also affected by the situation on the training places market, something which has altered over recent years.

- Young people's chances of securing a dual training place have improved in overall terms since 2006, this being mainly due to demographic developments (cf. Ulrich et al. 2013).

- Provision to assist with finding an occupation and training place has been expanded. In the light of the impending shortage of skilled workers, for example, companies are making increasing use of the Internet and television to advertise their training places. This also addresses the emotional level of choice of occupation in a targeted way.

How do young people experience the career selection process under these altered conditions and how do they become aware of their training occupation and training place? These questions will be investigated below on the basis of the information provided by the 2012 Applicant Survey carried out by the Federal Employment Agency (BA) and the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB) (cf. Table 1). The BA/BIBB Applicant Survey indicated that just under half (49%) of approximately 530,000 training place applicants registered with the Federal Employment Agency succeeded in progressing to dual vocational education and training by the late autumn of 2012. The following analyses relate exclusively to these successful applicants because only they could be asked how they became aware of their position within their current occupation.

Search remains difficult despite an easing of the situation on the training market

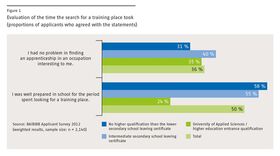

Even amongst successful applicants, only one in three (36%) stated in retrospect that they had experienced no problems in finding a training place in an interesting occupation. This was most likely to be true of young people with the intermediate secondary school leaving certificate, whereas persons who had not achieved any qualification higher than the lower secondary school leaving certificate or those in possession of a University of Applied Sciences /higher education entrance qualification experienced difficulties more frequently (cf. Figure 1). The problems experienced by many of those with a higher education entrance qualification is probably connected to the fact that they are concentrated in a small number of desirable training occupations in which they therefore experience a higher degree of competition. In the light of double upper secondary school leaving cohorts in some federal states, this competition was particularly marked in 2012 (cf. Beicht 2013). Those in possession of a higher education entrance qualification also frequently felt that they were inadequately prepared for their training place search.

Table 1: Profile of the 2012 BA/BIBB Applicant Survey

Young people receive a wide range of types of orientation assistance

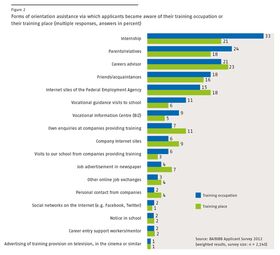

In view of the difficulties of selecting a career and seeking a training place, various kinds of orientation assistance were available to young people. Figure 2 shows which of these were actually helpful in the search for a training occupation or place.1 Internships are of central importance for the choice of an occupation and provided the vehicle via which one third (33%) of respondents became aware of their current training occupation. Other activities undertaken by companies and their associations, such as visits to and notices in schools, and information provided via traditional media (newspapers, television, cinema) and via new media (Internet pages, social networks) were significantly less likely to guide the young target group to their occupation.

Key figures in the private lives of young people also frequently provided career entry support. Just under a quarter (24 %) stated that they had learned of their training occupation from parents or relatives, and one in five (18%) had received this information via friends or acquaintances. Finally, the career advisors of the Federal Employment Agency (BA) were also a source of orientation assistance via which many applicants (21%) gained information on their current training occupation.

As far as other provision made available by the BA is concerned, the Agency's Internet sites, which are available everywhere and at any time, now enjoy higher significance than the stationary Vocational Information Centres.

Similar results are revealed for the question as to how young people became aware of their training place. The five forms of orientation assistance which were most likely to attract young people's attention to a training occupation were also the most frequent means via which they were led to their specific training places. Notwithstanding this, the internship was somewhat less significant in terms of finding a training place whereas careers advisors were most likely to guide the young people to their positions. The Internet presences of the BA, of companies or of other providers have a higher significance in searching for a training place than in choosing an occupation.

Figure 1: Evaluation of the time the search for a training place took

Figure 2: Forms of orientation assistance via which applicants became aware of their training occupation or their training place

Orientation depending on migration background and school leaving qualification

Transition research tells us that school leaving qualifications and migration background exert an influence on opportunities when searching for a training place (cf. Eberhard 2012). The extent to which these characteristics can also serve as a basis for the identification of differences in the successful use of forms of orientation assistance is shown in Tables 2 and 3. Only forms of orientation assistance which display differences in frequency of naming between the groups of at least five percentage points are listed.

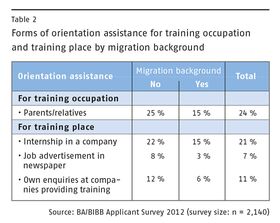

Compared to those not from a migrant background, applicants from a migration background were less likely to be made aware of their training occupations by parents and relatives (15% versus 25%). This result is consistent with the finding that young people from a migrant background are less likely to discuss their choice of occupation with their parents (cf. Beicht/Gei 2013, p. 11). One cause of this could be that parents with an immigration background are less familiar with the finer details of the German VET system and therefore find it more difficult to pass on relevant information.

As far as the training place is concerned, young people from a migrant background 2 were significantly less likely to become aware of their present position via internships or by making their own enquiries at companies providing training. This does not mean, however, that these young people are less likely to seek personal contact with companies. Beicht/Gei (2013), for example, showed that applicants from a migrant background are even likely to contact more companies than their age contemporaries not from a migrant background, although this establishment of contact seems less probable to be successful.

A differentiated consideration by school leaving certificate achieved shows that the higher the school leaving qualification of the successful applicants the more likely they are to have become aware of both their training occupation and training place via the Internet sites of the BA or of the company providing training. Whereas almost one in three of those in possession of a higher education entrance qualification learned of their training place via the Internet pages of the BA, the corresponding figure for young people who had achieved no higher a qualification than the lower secondary school leaving certificate was only just over one in ten. The situation with regard to internships was different. This was the means via which 41 percent of successful applicants who had achieved no higher a qualification than the lower secondary school leaving certificate became aware of their training occupation as well as being the vehicle through which just under one third of such young people found out about their training place. The latter was very rare in the case of those in possession of a higher education entrance qualification (6%). An interesting result is revealed with regard to parental support. Whereas young people who had achieved no higher a qualification than the lower secondary school leaving certificate were far more likely to have became aware of their training occupation via family members, such support played a comparatively minor role for those with a higher education entrance qualification.

In overall terms, the results point to the specific situation of those with a higher education entrance qualification. It is probably the case that their different occupational choice spectrum, their social background and their higher age mean that the types of orientation assistance significant to them are different to those of young people with lower school leaving qualifications.

Table 2: Forms of orientation assistance for training occupation and training place by migration background

Table 3: Forms of orientation assistance for training occupation and training place by school leaving qualification

Sufficient guidance, but too little support

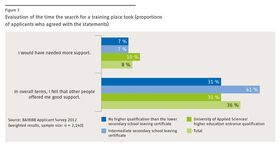

The analyses thus far demonstrate that successful applicants became aware of their occupation and training places via a wide range of types of orientation assistance. This does not, however, say anything about whether the types of orientation assistance were perceived to be sufficient. For this reason, the young people were also asked if they would have wished to have more guidance and support whilst searching for a training place (cf. Figure 3).

Although only a total of eight percent were of the view that they needed even more guidance, only 36 of successful applicants felt that they had received a good level of support. How can this be explained? Whereas respondents probably took "guidance" mainly to mean the imparting of information, the term "support" is more widely defined. It also includes emotional backing and assistance when problems occur (e.g. dealing with the flood of information or failed applications). Obviously the young people feel that these are the aspects that fall short.

Figure 3: Evaluation of the time the search for a training place took

Conclusion - internships and personal discussions

Despite a certain easing of the situation on the training places market, even successful applicants continue to find the search for training occupations and places to be difficult. If they are asked how they became aware of their current training occupation, it is revealed that particular significance is attached to personal discussions and specific experiences of work - internships at companies, talking to parents, relatives and friends and vocational guidance provided by the Employment Agency. These are the means via which young people are most likely to make their way. In contrast to what might be expected from the "Internet generation", web-based information and communication provision are of lesser relevance to vocational orientation. Only applicants in possession of a higher education qualification are more likely on average to be guided to their occupation and training place via Federal Employment Agency (BA) or company websites. It is surprising that the vocational guidance services provided by the BA are in overall terms approximately just as likely as parents and relatives to be stated to be successful orientation assistance measures due to the fact that higher significance has been ascribed to the parental home in other studies (cf. Beinke 2002).

We need to take into account, however, that the statistical population of the BA/BIBB Applicant Survey only includes persons who have voluntarily sought placement assistance from the BA rather than comprising all those in Germany who are interested in training. Young people whose vocational orientation is strongly guided by their parental home are probably under-represented. In retrospect, applicants wish to have access to persons who provide them with comprehensive practical and active support rather than an expansion of advisory provision where the main focus is on the imparting of information. Career entry support and mentoring programmes have been introduced for young people expected to have difficulties in making the transition to vocational education and training. The analyses show, however, that even many applicants in possession of a higher education entrance qualification feel that they are poorly prepared for the search for an occupation and training place and also experience problems in this process. For this reason, the further development of transition support should not in future be restricted to the area of providing support for disadvantaged young people.

Literature

Beicht, U.: Doppelte Abiturjahrgänge: Veränderte Chancen für Jugendliche am Ausbildungsmarkt [Double upper secondary school leaving cohorts - changed opportunities for young people on the training market]. In: BWP [Vocational Training in Research and Practice]42 (2013) 6, pp. 38-41 - (status: 05.12.2013)

Beinke, L.: Familie und Berufswahl [Family and choice of occupation]. Bad Honnef 2002

Eberhard, V.: Der Übergang von der Schule in die Berufsausbildung. Ein ressourcentheoretisches Modell zur Erklärung der Übergangschancen von Ausbildungsstellenbewerbern [Transition from school to vocational education and training - a theoretical resources-based model to explain the transition chances of training place applicants]. Bonn 2012

Eberhard, V.; Krewerth, A.; Ulrich, J. G.: Berufsbezeichnungen und ihr Einfluss auf die beruflichen Neigungen von Jugendlichen [Occupational titles and their influence on the vocational predispositions of young people]. In: ZBW Supplement 24 (2010), pp. 127-156

Neuenschwander, M. P.; Hartmann, R.: Entscheidungsprozesse von Jugendlichen bei der ersten Berufs- und Lehrstellenwahl [Decision-making processes of young people at initial choice of occupation and apprenticeship]. In: BWP [Vocational Training in Research and Practice]40 (2011) 4, pp. 41-44 - (status: 05.12.2013)

Ulrich, J. G. u. a.: Ausbildungsplatzangebot und -nachfrage [Training place supply and demand]. In: BIBB (Ed.): Data Report to accompany the 2013 Report on Vocational Education and Training. Bonn 2013, pp. 14-29

ANDREAS KREWERTH

Research associate in the “Vocational Training Supply and Demand / Training Participation” Division at BIBB

VERENA EBERHARD

Dr., Research associate in the “Vocational Training Supply and Demand / Training Participation” Division at BIBB

JULIA GEI

Research associate in the “Vocational Training Supply and Demand / Training Participation” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 1/2015): Martin Stuart Kelsey, Global Sprachteam Berlin

footnotes

-

1

The questionnaire used a dichotomous scale (true/not true), via which young people stated for all 17 forms of orientation assistance whether they had become aware of their training occupation or training place via such a means. Multiple responses were also possible.

-

2

Applicants born in Germany who are in possession of German citizenship only and who have only learned German as their native language are considered to be Germans without a migrant background. All other persons are assumed to be from a migrant background. On this basis, 19 percent of applicants are deemed to be from a migrant background.