Recognition of foreign professional qualifications following the nursing professions reform

Anke Jürgensen

The numbers of applications for professional recognition in the healthcare professions are rising continually and have been heading up the statistics in this regard for years. This is highly welcome given the shortage of skilled nursing staff in Germany, but applicants seeking to negotiate the recognition procedure face a long route. This article clarifies the legal foundations underlying the process, looks at which challenges are being produced by the new Nursing Professions Act and presents possible ways towards a solution.

Shortage of skilled staff and immigration of nurses

Germany has had a shortage of skilled nursing staff for years. The average number of vacancies in nursing and geriatric nursing in 2018 was just under 40,000 (cf. BA 2019, p. 12). The need for skilled nursing staff can be expected to continue to grow in the wake of demographic epidemiological developments and medical progress. Immigration of nurses is viewed as one potential remedy, and various regulatory and recruitment measures were already put in place by (economic) policy makers in 2012 in order to support this (cf. Pütz et al. 2019, pp. 39 ff.).

Irrespective of whether nursing professionals are recruited from abroad or not, all those who have acquired a foreign professional qualification and are not covered by automatic recognition within the EU are required to complete a recognition procedure of several months’ duration before they are permitted to exercise their profession in Germany. In the case of the nursing professions, this procedure is regulated by specific laws governing the professions and by training and examination ordinances.

Legal foundations of the recognition procedure

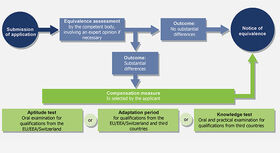

The formal procedural process pursuant to the new Pflegeberufegesetz (PflBG) [Nursing Professions Act] has not significantly altered compared to the separate laws that regulated nursing and geriatric nursing up until 2019. Successful completion of a programme of vocational or higher education training and of a state examination remains the primary prerequisite for authorisation to practise as a nurse. The legal foundations for authorisation to practise are governed by §§ 40 and 41 of the PflBG. These provisions draw a distinction on the one hand between qualifications obtained in a member state of the EU, in a state which is party to the European Economic Area Treaty (EEA) or in Switzerland and on the other hand qualifications that have been acquired in a third country. As the figure shows, the recognition procedure will result in a notice of equivalence being issued as long as no substantial difference to the German reference occupation is identified. The recognition authorities will assign compensation measures if any substantial differences are found. Evidence of knowledge of German, of medical fitness and of reliability are likewise required before authorisation to practise in Germany can be granted. Partial recognition for nurses is not possible.

Assessment and evaluation

Applicants have to submit various pieces of evidence in order to allow a comprehensive and meaningful specialist evaluation of their qualification to take place. These include certification of entitlement to exercise the profession in the country of origin, training and examination certificates and further evidence of qualification in the form of advanced training documentation or employment references. Any diploma supplements that may be available should also be presented.

A comparative measure is used in order to ascertain whether and the extent to which an applicant’s qualification is equivalent. Directive 2005/36/EC serves as the basis for the evaluation of qualifications from the EU/EEA/Switzerland. The levels of qualification stated in Article 11 and the minimum requirements stipulated in Article 31 Paragraph 7 a-h of Directive 2005/36/EC (amended by Directive 2013/55/EU) set out conditions for admission (ten years of general school education), the duration of training (4,600 hours) and the distribution and learning venues of practical and theoretical elements of training. Applicants also need to demonstrate possession of the competencies required for carrying out the relevant professional tasks stated in the Directive.

The evaluation of qualifications from third countries is governed by the PflBG, by the Pflegeberufe-Ausbildungs- und -Prüfungsverordnung (PflAPrV) [Training and Examination Ordinance for the Nursing Professions] and by Article 11 of the EU Directive cited above. Scrutiny needs to take place on this basis as to whether any differences exist in terms of level, in respect of the main focuses and areas covered by theoretical and practical training or with regard to regulated and other professional tasks performed by nurses in Germany. The reference standards for this evaluation consist of § 4 PflBG (reserved tasks), § 5 PflBG (training objective) and the competencies listed in Annexes 2–4 of the PflAPrV and deemed to be necessary for the qualified execution of nursing activities.

Challenges in the evaluation of professional qualifications

A decision regarding equivalence cannot generally be made solely on the basis of qualifications certificates containing summaries of subjects studied. In order to undertake a comprehensive assessment and arrive at meaningful outcome, a curriculum should also be available. The rareness of the availability of informative curricula, especially in the case of qualifications from third countries, has been a problem in the past. Now, however, content evaluation faces a further challenge in light of the PflBG. Nursing training in Germany is designed in a subject-integrative way, it is based on a system of learning fields, and adopts a competence-oriented approach. By way of contrast, applications for professional recognition mostly involve certificates which are set out in conventional subjects (such as anatomy, professional skills, and pathology). The competence catalogues in Annexes 2–4 of the PflAPrV are based on an employment-oriented definition, whereas the documents to be examined, especially if a subject-based system is used, do no more than present the (cognitive) prerequisites for certain competencies. Seeking to use documents to ascertain competencies is, however, a contradiction in itself. Competencies can only be identified on the basis of occupational activity (cf. Rüschoff 2019). The legislation, however, only provides for knowledge or aptitude tests, in which applicants are required to demonstrate competencies by performing professional or occupational tasks, in cases where either prior specialist evaluation of evidence of qualifications has led to the conclusion that substantial differences exist compared to training in Germany (cf. § 40 Paragraph 2 PflBG) or if applicants are unable to submit necessary evidence through no fault of their own (cf. § 40 Paragraph 3 PflBG).

Compensation measures

Depending on the qualification’s origin or the choice made by an applicant, compensation measures for the recognition of a nursing qualification encompass a practical aptitude test, a practical and oral knowledge test, or an adaptation period (see figure). As data from the official statistics indicates, applicants tend to opt for an examination rather than a course when selecting a compensation measure (see also the poster in the centre of the journal). Their motives for doing so can only be a matter for speculation. An examination may bring the promise of a more rapid end to the recognition procedure and for this reason be preferred to an adaptation period, which can last for up to three years. Another possibility, however, is that the available evidence is too scanty or not meaningful enough to permit any conclusion regarding whether the applicant is in possession of the competencies necessary to exercise the profession. In such cases, an aptitude or knowledge test may serve as a means for delivering the proof that the documents cannot provide.

In 2018, just under 11,500 applications for equivalence in the profession of registered general nurse were submitted. This represents an increase of more than 30 percent compared to the previous year (cf. BMBF 2019, p. 32). These high numbers of applications and the extensive amount of assessment that may subsequently be required mean that it is currently almost impossible to comply with the prescribed duration of up to four months before a notice of assessment is issued (cf. § 43 PflAPrV). Even after a notice has been received, authorisation to practise as a nurse is then delayed for several months because of the backlog created by the large number of applicants opting for an examination (cf. BMBF 2019, p. 45).

Possible ways towards a solution

§ 66a of the PflBG, a transitional provision recently enacted, may be viewed as an immediate regulatory measure. This states that the old laws regulating professions in nursing and geriatric nursing may be used for the purpose of recognition until the end of 2024. Such a step introduces an initial delay to the necessity of using the extensive catalogue of competencies contained within the PflAPrV as a yardstick for evidence of qualifications or as a basis for the content structuring of compensation measures.

On the policy side, various initiatives are currently being instigated with the aim of making it possible for nurses from abroad to commence work in the profession rapidly. Following the reform of the nursing professions in 2019, the Federal Government set up a concerted scheme to support the recruitment of nurses called “Konzertierte Aktion Pflege” (KAP). Within this project, “Working Group 4” is pursuing an agreed objective to improve the general conditions which relate to the acquisition of nurses from abroad (cf. BMFSFJ 2019, pp. 129ff.). Numerous representatives from professional associations and the federal states have pledged amongst other things to initiate measures to standardise evaluations of certificates and to introduce uniformity with regard to the content requirements of compensation measures. Even though it would be desirable to accelerate professional recognition procedures in order to arrive at a rapid way of remedying the existing shortage of skilled staff, the need to ensure patient safety means that no cuts should be made to the specialist contents of the examination.

Literature

BUNDESAGENTUR FÜR ARBEIT (BA): Arbeitsmarktsituation im Pflegebereich. Nürnberg 2019

BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR BILDUNG UND FORSCHUNG (BMBF): 5. Bericht zum Anerkennungsgesetz. 2019

BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR FAMILIE, SENIOREN, FRAUEN UND JUGEND (BMFSFJ) (Hrsg.): Konzertierte Aktion Pflege. Berlin 2019

PÜTZ, R. u.a.: Betriebliche Integration von Pflegefachkräften aus dem Ausland. Düsseldorf 2019

RÜSCHOFF, B.: Methoden der Kompetenzerfassung in der beruflichen Erstausbildung in Deutschland. Bonn 2019

ANKE JÜRGENSEN

Academic researcher at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 2/2020): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin