Train existing employees or recruit new staff?

Strategies adopted by German SMEs to meet technological change

Myriam Baum, Felix Lukowski

Increasing digitalisation is playing an important role for SMEs as well as large enterprises. The way of working is changing, and task demands for employees are growing. How are companies attempting to meet these rising requirements? Are new staff being recruited, or are new career opportunities opening up for existing workers? This article investigates these questions using data from the BIBB Training Panel as a basis.

Digitalisation is leading to new work requirements

The permeation of the world of work by new digital technologies is causing fundamental changes to work processes, in both the manufacturing industry (cf. HIRSCH-KREINSEN/WEYER 2014) and in the services sector (cf. STAMPFL 2011). This is resulting in structural shifts on the labour market, as existing occupations alter, new occupations come into being and certain occupations even disappear (cf. HELMRICH et al. 2016). At the same time, employee tasks are also undergoing change (cf. AUTOR/LEVY/MURNANE 2003). As use of digital technology increases, we can thus observe that activities in the workplace are becoming more demanding (cf. LUKOWSKI/NEUBER-POHL 2017). This rise in the requirements level means that employees need the right skills in order to be able to tackle tasks in a professional manner.

Companies have two possible ways of countering the new requirements – external recruitment or continuing training for existing employees (cf. DEVARO/MORITA 2013).

Internal training measures provide a vehicle via which workers are able to acquire the necessary competences to deal with digital technology, and indeed analyses reveal a positive correlation between digitalisation and continuing training (cf. LUKOWSKI/NEUBER-POHL 2017). Nevertheless, such refresher training programmes do not necessarily deliver an occupational benefit for the employees. For this reason, the present article will place the emphasis on so-called “upgrading training courses” (leading to qualifications such as certified senior clerk, master craftsman and technician).

Such training leads to the acquisition of a formal higher qualification, which usually results in greater responsibility and better remuneration and therefore constitutes a career jump for many employees (cf. HALL 2014, FLAKE/WERNER/ZIBROWIUS 2016). Even though the qualifications obtained via most upgrading training programmes are not exclusively related to digitalisation, dealing with digital technologies forms an integral component of advanced training content (cf. PFEIFFER/WESLING 2016). We may consequently assume that the digital competencies necessary within the occupation are imparted within the scope of upgrading training programmes. The opposite approach to this internal training is to recruit new employees who already possess the relevant qualifications to meet the latest requirements.

The changes to work demands that have occurred in the wake of digitalisation do not only affect large companies. SMEs make up the bulk of companies in Germany. This means that they occupy a special position within the economic system (cf. SÖLLNER 2016). For this reason, the intention below is to investigate the extent to which use of technology in SMEs is associated with support from internal upgrading training and how this influences firms’ recruitment behaviour.

Database and identification of the degree of digitalisation

The 2016 survey wave of the BIBB Training Panel (cf. Information Box) included 1,700 companies which are designated SMEs according to the definition of the EU Commission. This definition encompasses companies with up to 249 employees and a maximum turnover of € 50 million. A balance sheet total of up to € 43 million may be used as an alternative point of reference instead of the threshold turnover of € 50 Million.1

The BIBB Establishment Panel

The BIBB Establishment Panel on Training and Competence Development (BIBB Training Panel) is a regular annual survey which has been conducted since 2011. It is used to collect representative longitudinal data on the training activities of companies in Germany. Around 3,500 establishments take part. Selection takes place via a disproportionately stratified sample of the statistical population of all companies with one or more employees subject to mandatory social insurance contributions. The main focuses of the survey are human resources management, companies’ initial and continuing vocational education and training activities and the recruitment of skilled workers. Data is collected via computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI).

A special module on the digitalisation of the world of work was introduced for the 2016 survey wave. The present article uses the questions on firms’ use of technology posed in this module to conduct analyses on the basis of company degree of digitalisation.

In the special supplementary for the 2016 survey wave, information on the following eight categories of digital technologies was collected. These vary strongly in terms of penetration. Virtually all companies have computers/smartphones (99.6%) and digital network technologies (95.8%). Many companies also use data security technologies (89.2%) or technologies to network with customers (68.2%). Computer-aided work equipment (36.5%), technologies for the processing and storage of data (34.5%), technologies for networking with suppliers (32.0%) and human resources or work organisation technologies are all less common.

The degree of company digitalisation is calculated from the total of technologies used at the firm. Level one comprises companies with one or two instances of use of digital technologies. This produces an eight stage index, which extends from “no digitalisation” (0) to “very high degree of digitalisation” (7). Figure 1 shows how SMEs are distributed across the index.

In overall terms, only very few companies exhibit the two extremes of either no digitalisation (2.1%) or very high digitalisation (4.3%). By way of contrast, almost half of companies are located in the intermediate area by dint of the fact that they show a degree of digitalisation of 3 (23.2%) or 4 (21.8%). In order to analyse the correlation between degree of digitalisation and upgrading training programmes or instances of recruitment of new staff, the index was divided into three. This means that the number of categorisations included in the digitalisation index is reduced from eight levels to the levels 1 to 3. 1 denotes a low degree of digitalisation, previously covered by levels 0 to 2. A total of 21.7 per cent of companies are in this category. Most companies (62.2%) have a medium degree of digitalisation, comprising the previous levels of 3 to 5. A high degree of digitalisation (level 3), consisting of the original levels 6 to 7, is shown by 16.1 per cent of companies. This threefold division was undertaken with the assumption that more heterogeneous results could be achieved than if consideration took place on the basis of eight levels. In addition, some groups in the eight-level index contain only a small number of companies.

Dealing with the new requirements brought about by digitalisation

As described above, upgrading training programmes for employees may represent one strategy via which companies can address the new demands made of their staff as a result of digitalisation.

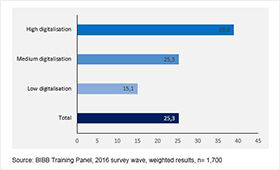

Figure 2 shows the proportion of SMEs which fund upgrading training programmes for their employees. 17.8 per cent of companies with a high degree of digitalisation support upgrading training, whereas the corresponding proportions for companies with medium or low digitalisation are significantly lower (9.4 % and 3.2 % respectively). The total across all companies is 9.4 per cent. A significant slightly positive correlation (0.16***) is revealed between upgrading training and degree of digitalisation.

Another possible strategy via which companies can tackle the new demands is to recruit skilled workers who already possess the necessary qualifications (cf. DEVARO/MORITA 2013). The BIBB Training Panel surveys whether a company has recruited new employees in the previous year (not including trainees) and whether staff have left the company. For the purpose of the analysis, newly recruited workers are only counted as such if this has led to a growth in the number of employees. In the case of companies which have recruited as many new employees as workers who have departed, no differentiation can be made as to whether these new recruits have simply replaced the departees or have been taken on as new workers who are better able to deal with the new technologies. They are then recorded in the dichotomous variable under “no instances of new recruitment”. Figure 3 shows the distribution of instances of newly recruited employees across the SMEs.

There is a significant and weakly positive correlation between new recruitment by a company and its degree of digitalisation (0.09***).

External recruitment or upgrading training?

For the purpose of the analysis, two separate logistic regression models are calculated, in which the degree of digitalisation represents the independent variable. In the logistic regression, the dependent variable comprises one variable with only two characteristics. This means that something is present or it is not. In contrast to an OLS regression, the logistic regression models the probability that the dependent variable is present (cf. BEST/WOLF 2010).

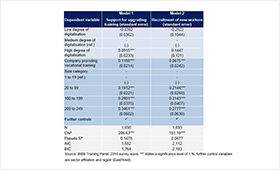

The first model investigates the influence of the degree of digitalisation of a company with regard to whether support is provided for upgrading training programmes. In the second model, the dependent variable is accordingly represented by instances of new recruitment. In addition, structural characteristics such as sector affiliation, company size, region (East or West Germany) and whether the company offers vocational training are included as control variables in order to avoid any distortions of the results.

The table shows the marginal effects and the relevant fit dimensions of the logistic regressions. In the first model, a highly significant correlation between degree of digitalisation and support for upgrading training can be identified. In companies with a high degree of digitalisation, the likelihood that they will support employees with upgrading training is 9.2 per cent higher than at firms with a medium degree of digitalisation. By way of contrast, no significant difference can be ascertained between companies with a low digitalisation and those with a medium degree of digitalisation. The likelihood that companies providing vocational training will support upgrading training is also significantly higher (11.9%). This is plausible given the fact that upgrading training programmes are usually pursued as a further qualification following completion of dual VET. We can also observe that significant differences in respect of company size occur within the group of SMEs. Compared to firms with up to 19 employees, the likelihood that upgrading training will be supported is around 34 per cent higher for companies with between 200 and 249 employees, about 19 per cent higher for firms with between 20 and 99 employees, and approximately 29 higher in the case of companies with between 100 and 199 employees. This means that there is a significant rise in the probability that upgrading training will be offered once a company’s workforce is greater than 20 in number. One of the reasons for this effect is that the proportion of companies providing vocational training rises in line with increasing company size (cf. TROLTSCH 2017).

On the other hand, degree of digitalisation cannot be shown to exert any significant effect on instances of new recruitment by a company (Model 2).

Upgrading training acting as a career boost in the age of digitalisation

If we consider human resources or recruitment strategies against the background of the respective degree of digitalisation, no significant relationship between degree of digitalisation and instances of new recruitment can be identified. By way of contrast, employees at companies with a higher degree of digitalisation are more likely to take part in upgrading training. These programmes foster both professional skills and the digital competencies which are becoming increasingly necessary within the occupation. In conjunction with the completion of higher formal training, these competences open up new career opportunities for employees. Upgrading training may result in an expanded area of tasks and responsibility as well as enhancing wages. For their part, the companies obtain skilled staff who are able to offer the skills required to deal with new digital technologies. For SMEs in particular, which usually do not have the same financial resources at their disposal as large enterprises, this may deliver a significant competitive edge over rival firms. The important aspect here is that advanced training contents are adapted to meet new technological developments on an ongoing basis. This enables both employers and employees to benefit from upgrading training programmes.

Literature

AUTOR, D. H.; LEVY, F.; MURNANE, R. J.: The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. In: Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (2003) 4, pp. 1279–1333

BEST, H.; WOLF, C.: Logistische Regression [Logistic regressions]. In: WOLF, C.; BEST, H. (Eds.): Handbuch der sozialwissenschaftlichen Datenanalyse [Handbook of socio-scientific data analysis]. Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 827-854

DEVARO, J.; MORITA, H.: Internal promotion and external recruitment: a theoretical and empirical analysis. In: Journal of Labor Economics 31 (2013) 2, pp. 227–269

FLAKE, R.; WERNER, D.; ZIBROWIUS, M.: Karrierefaktor berufliche Fortbildung: Einkommensperspektiven von Fortbildungsabsolventen [Advanced vocational training as a career factor – income prospects for those who have completed advanced training]. In: IW-Trends 43 (2016) 1, pp. 85–103

HALL, A.: Lohnt sich Aufstiegsfortbildung? Analysen zum objektiven und subjektiven Berufserfolg von Männern und Frauen [Is upgrading training worthwhile? Analyses of the objective and subjective occupational success of men and women]. In: BWP 43 (2014) 4, pp. 18-21 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/7370 (retrieved: 01.08.2017)

HELMRICH, R. et al.: Digitalisierung der Arbeitslandschaften – Keine Polarisierung der Arbeitswelt, aber beschleunigter Strukturwandel und Arbeitsplatzwechsel [Digitalisation of working landscapes – no polarisation of the world of work but accelerated structural change and job switching]. Bonn 2016 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/show/8169 (retrieved: 01.08.2017)

HIRSCH-KREINSEN, H.; WEYER, J.: Wandel von Produktionsarbeit – "Industrie 4.0” [Change of production work – “industry 4.0]. Dortmund 2014

LUKOWSKI, F.: Betriebliche Weiterbildung in Zeiten der Digitalisierung – Anspruchsvoller arbeiten, mehr lernen? [Company-based continuing training in times of digitalisation – more challenging work and more learning?]. In: DIE Zeitschrift für Erwachsenenbildung [Journal of Adult Education] (2017) 3, pp. 42–44

LUKOWSKI, F.; NEUBER-POHL, C.: Digital technologies make work more demanding (German version in: BWP 46 (2017) 2, pp. 9–13) – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/8310 (retrieved: 01.08.2017)

PFEIFFER, I.; WESLING, M.: Das Handwerk in Zeiten der Digitalisierung – Beruflich qualifizierte Fachkräfte sind und bleiben das A und O [Craft trades in the era of digitalisation – skilled workers with vocational qualifications remain the essential thing]. In: Wissenschaft trifft Praxis [Academic research meets practice] (2016) 5, pp. 30–36

SÖLLNER, R.: Der deutsche Mittelstand im Zeichen der Globalisierung [German SMEs and the influence of globalisation]. In: Wirtschaft und Statistik [Economics and Statistics] (2016) 2, pp. 107-109

STAMPFL, N. S.: Die Zukunft der Dienstleistungsökonomie – Momentaufnahmen und Perspektiven [The future of the service economy – snapshots and prospects]. Berlin/Heidelberg 2011

TROLTSCH, K.: Betriebliche Ausbildungsbeteiligung – Ergebnisse der Beschäftigungsstatistik zur Ausbildungsbeteiligung [Company participation in training – results of the employment statistics on participation in training]. In: Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2017 [Data Report to accompany the 2017 Report on Vocational Education and Training], pp. 214-226 – URL: www.bibb.de/datenreport2017 (retrieved: 01.08.2017)

MYRIAM BAUM

Student Associate in the “Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment” Division at BIBB

FELIX LUKOWSKI

Research Associate for the BIBB Training Panel in the “Sociology and Economics of Vocational Education and Training” Department at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 5/2017): Martin Kelsey, GlobalSprachTeam, Berlin