Starting dual training or continuing to attend school?

Educational preferences of Year 9 pupils and how these change

Annalisa Schnitzler, Mona Granato

At the end of lower secondary education, many young people are faced with the question of how they should proceed. Should they continue at school, undertake a practical placement, gain experience abroad or begin dual training? This article investigates the factors which influence their choice and how the educational preferences of pupils change over the course of Year 9. The basis for this investigation is provided by data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), which was evaluated within the scope of the BIBB project “Educational orientation and decision-making of adolescents in the context of competing educational opportunities”.

Biographical decision regarding the change in status from school to career

Despite signs of easing in the vocational education and training market due to a declining number of applicants, as well as an increase in vacant training places, the number of applicants that did not find a training place in 2015 was higher than the number of vacant places (cf. MATTHES et al. 2016). It is in light of these developments that various and – in some cases – contradictory theses are under discussion. On the one hand, it is argued that the number of secondary school leavers interested in a dual training programme is on the decline, as young people are increasingly looking towards other education and training options. On the other hand, it is said that young people – particularly those of lower secondary school level – are still shying away from going straight into a dual training programme after completing their compulsory schooling due to reports of unsuccessful applications. The change of status from school to career presents young people with the challenge of making far-reaching decisions from the perspective of their future education, training and occupational biography. Selecting the appropriate education and training options therefore represents a major step towards their professional life. This decision-making process is based on personal, social and institutional factors.

Personal factors include dispositions such as career interests, values, expectations and perceptions of oneself (cf. HIRSCHI 2013), as well as academic requirements and socio-demographic factors. Social factors not only exert an influence via the particular environment in which young people socialised and, by extension, on the specific behaviours expected for these social surroundings (cf. BOURDIEU 1987), but also via their social background. The ambitions of parents for their children to achieve at least the same social status that they hold influences young people’s educational decisions in the sense of an inter-generational reproduction of the achieved social status (cf. BOUDON 1974). A career is therefore a significant factor in terms of young people’s social positioning (cf. GOTTFREDSON 1985). That said, educational decisions are never made without institutional context, which not only presents options, but also highlights institutional limitations (cf. HEINZ et al. 1987; DOMBROWSKI 2015). They often represent a compromise, therefore, between aspirations and genuine options, entailing a change of direction for young people over the course of time. This allows self-selection processes to become effective in such a way that young people already anticipate institutional obstacles when finding their bearings and restrict the educational pathways they choose to consider. Career orientation measures are also attributed to the institutional context.

The education and training options being considered by young people should therefore be examined with these factors in mind and analysed as part of the BIBB research project “Educational orientation and decision-making of adolescents in the context of competing educational opportunities”1 . It is on this basis that the educational preferences of young people in Year 9 along with the personal, social and institutional factors that influence these will be depicted. This article also highlights the change in preference over the course of Year 9 and identifies the factors that give rise to this rethink. With this in mind, are young people more likely to respond to influences from the education and training market – and therefore anticipate unfavourable prospects – or to influences from their social environment, which are associated with higher education and training aspirations?

The empirical analyses use NEPS data (cf. info box). The sample forming the basis of the study is made up of 6,650 pupils in Year 9, who were surveyed on their future educational preferences both at the start of the academic year and again in the second semester.

National Educational Panel Study (NEPS)

This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Studuy (NEPS): Starting Cohort Grade 9, doi:/10.5157/NEPS:SC4:4.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data was collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research, which was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) [Federal Ministry of Education and Research]. As of 2014, the NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network. It takes longitudinal data on educational and training achievements, educational processes, and competence development in formal, non-formal and informal contexts over the entire life span (cf. www.lifbi.de and BLOSSFELD/ROßBACH/VON MAURICE 2011).

The article uses the first two waves of research for Starting Cohort 4 – autumn 2010 and spring 2011 – which involved surveying more than 15,500 Year 9 pupils at general education schools. Included here are pupils attending all types of school with the exception of schools for children with learning difficulties and grammar schools.

Which educational pathways do young people prefer in Year 9?

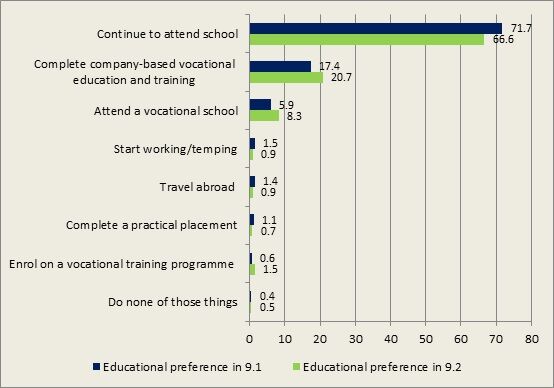

Figure 1 illustrates the educational preferences of young people in the first and second semester of Year 9. This is not simply a case of idealistic thinking, but rather realistic preferences for what they are actually – or most probably – going to do after Year 9. The vast majority of respondents plan to remain at school beyond Year 9, and although this proportion diminishes over the course of the school year, it still represents two thirds of the group. The most popular alternative to staying at school is to complete company based vocational education and training (i.e. vocational training in the dual system), as noted by around one in five respondents. Other alternative options are relatively insignificant by comparison. At the start of Year 9, the focus on dual training programmes is considerably more widespread among pupils of lower secondary school level than their intermediate-level counterparts (27 % vs. 14 %). Whereas pupils of lower secondary school level maintain this preference in the second semester (27 %), those of intermediate secondary school level become increasingly interested in this option by the end of Year 9 (+8 percentage points). In terms of the gender divide, around one in seven girls plan to opt for a dual training programme regardless of when they were asked, compared to one in five boys asked in the first semester, and one in four in the second.

Figure 1: Realistic educational preferences in the period after Year 9 in the first (9.1) and second (9.2) semester (figures in %)

Source: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi), National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), Starting Cohort 4, doi:/10.5157/NEPS:SC4:4.0.0, independent calculations from the BIBB research project “Training orientations”

Who prefers dual education and training?

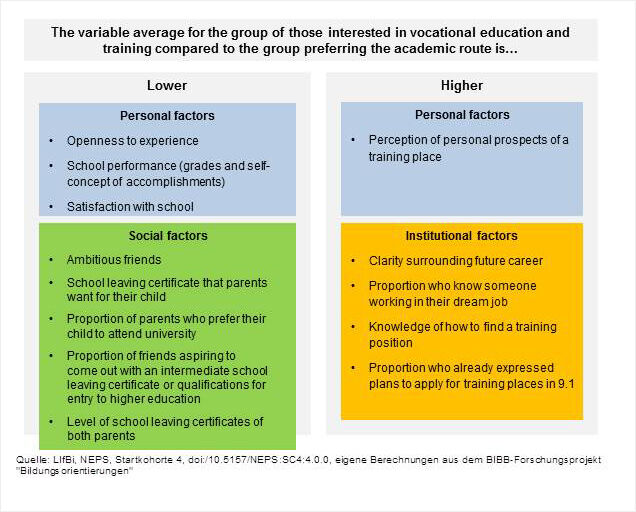

To find out which pupils are interested in dual VET at the end of Year 9, T-tests are devised to compare the group of potential training place applicants and the group preferring to remain at school (cf. Figure 2). These tests take personal factors (such as socio-demographic, dispositional and academic characteristics) into consideration along with influences from the social environment and the institutional context, including the career orientation process. Other institutional aspects are portrayed as proxies by young people’s subjective assessments of success and prospects and categorised under personal factors.

Young people aspiring to be accepted into a dual education and training programme describe themselves as less imaginative and artistic and therefore less open. This is the only difference between the groups with respect to the general self-concepts under analysis. With regard to educational self-concepts, those interested in a dual education and training programme appear less self-assured in relation to both individual subjects and their overall academic ability. This perception goes hand in hand with comparatively poor grades in German and mathematics, and lower educational satisfaction. As for their social environment, this group describes their friends as less ambitious, and the proportion of these friends aspiring to a higher-level school leaving certificate is lower by comparison. Furthermore, both parents have a lower-level school leaving certificate on average and are less focused on directing their child towards the academic route, including achieving entrance qualifications for university or an intermediate school leaving certificate. In the career orientation process, those interested in vocational education and training have a clearer picture of their future career and are more likely to know someone working in their dream job. They also seem to demonstrate a better understanding of how to acquire a training place, more confidence in their ability to secure one, and a greater likelihood of applying for one over the course of Year 9. Furthermore, those looking towards company-based training are more likely to be young men (63 % vs. 50 % of those wishing to remain at school) attending a lower-level secondary school than any other school type (52% vs. 29%) and less likely to come from a migration background (27% vs. 32 %).

Figure 2: Comparison between the group of potential training place applicants and those preferring to remain at school in 9.1 using selected characteristics

Only significant differences were reported (p<.05).

Source: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi), National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), Starting Cohort 4, doi:/10.5157/NEPS:SC4:4.0.0, independent calculations from the BIBB research project “Training orientations”

Who changes their preference over the course of Year 9?

As the year goes on, some pupils decide they no longer wish to pursue the academic route and instead turn to other options such as a vocational education and training programme (cf. Figure 1).

In spite of this general trend of moving away from academia, there are also a number of students who change their mind in the opposite direction. Of the 1,158 young people who were leaning towards company-based training at the start of Year 9, only 588 of these listed this as their most likely option when asked again in the second semester. 403 young people are now aspiring to continue with their studies and the remaining participants listed alternative options in small numbers.

The Table reveals which factors could encourage young people to change their mind from their initial ambition to complete an education and training programme in favour of staying at School 2.

The logistical regression covered personal factors, the social environment, and the career orientation process as an institutional factor on a step-by-step basis.

The only variables taken into consideration were those with a significant difference in average values between those who maintained their education and training preference and those who changed their mind in favour of staying at school.

The socio-demographic variables alone have no direct impact on the likelihood of a change in preference (Step 1). Only the lower secondary school visit – in conjunction with social variables and the career orientation and application processes – demonstrates an effect in Step 4 that lower-level secondary school pupils are more likely to change their preference in favour of staying at school.

Surprisingly, the likelihood of changing preference is lower when young people are happier at school (Step 2); however, the effect is relatively small and no longer significant once the career orientation and application processes is taken into consideration (Step 4). The likelihood of changing preference in favour of staying at school increases when pupils are convinced of their ability to achieve an intermediate school leaving certificate and believe that pupils from lower-level secondary schools are at a disadvantage when looking for a training place. The likelihood of changing increases if the father holds a higher-level school leaving certificate (Step 3).

On the other hand, the aspiration to achieve the same level of education and training as one’s parents has no significant impact on the change in preference, nor does the number of friends aiming to achieve an intermediate school leaving certificate. In terms of work experience, the likelihood of changing preference decreases among young people who already have a regular side job alongside their studies, whereas a practical placement has no real impact. It comes as no surprise that for those who have a training place lined up, the likelihood of deciding to stay at school is significantly lower.

Table: Likelihood of changing preference from completing a company-based training in 9.1 to remaining at school in 9.2

Source: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi), National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), Starting Cohort 4, doi:/10.5157/NEPS:SC4:4.0.0, independent calculations from the BIBB research project “Training orientations”

Guide: In this hierarchical, logistical regression, values greater than 1 signify that this factor increases the likelihood of a change in preference, while values lower than 1 signify a decrease; for example, the likelihood of a change in preference decreases if the young person regularly works as a temp.

Evaluation of personal prospects at school and in the education and training market influences educational preferences

The results highlight that, as early as Year 9, a considerable proportion of young people can already imagine themselves going straight into a vocational education and training programme. On one hand, this preference appears to be dependent on personal school experiences; on the other, the general education and training aspirations of their social environment also has a part to play. Furthermore, pupils interested in embarking on a vocational education and training programme tend to have a sounder vocational outlook and are more optimistic about their prospects.

Nevertheless, a number of pupils are ultimately abandoning their original education and training plans in favour of staying at school. Regardless of their current academic performance, these young people appear to change their plans in favour of staying at school “just in case” due to their higher estimation of their future academic prospects and a fear of faring badly on the education and training market. This change can be considered a self-selection process. As a result, they are for the time being lost for the vocational education and training market as prospective apprentices. The effects of this change in direction on their future career remain to be seen. The aforementioned BIBB research project aims to investigate a number of areas, including whether remaining at school actually contributes to young people achieving an advanced school leaving certificate, and what education and training options they then tend to pursue. As for the actual consequences of leaving school after Year 9 on a young person’s future career, the BIBB is currently investigating this area as part of the “NEPS-BB” project funded by the BMBF 3 . This project aims to analyse how young people who leave school with a lower secondary or no school leaving certificate make the transition into vocational education and training programmes and a career.

Literature

BLOSSFELD, H.-P.; ROßBACH, H.-G.; VON MAURICE, J.: Education as a Lifelong Process – The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In: Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft (2011) Sonderheft 14, pp. 19–34

BOUDON, R.: Education, opportunity and social inequality. Changing prospects in Western society. New York 1974

BOURDIEU, P.: Esquisse d'une théorie de la pratique [Outline of a theory of practice]. Paris 1987

DOMBROWSKI, R.: Berufswünsche benachteiligter Jugendlicher. Die Konkretisierung der Berufsorientierung gegen Ende der Vollzeitschulpflicht. [Career aspirations of disadvantaged young people. Determining career orientation towards the end of full-time education]. Bielefeld 2015

GOTTFREDSON, L. S.: Role of self-concept in vocational theory. In: Journal of Counseling Psychology 32 (1985) 1, pp. 159–162

HEINZ, W. et al.: „Hauptsache eine Lehrstelle“. Jugendliche vor den Hürden des Arbeitsmarktes [„Apprenticeships: The holy grail“. Young people facing the hurdles of the job market]. Weinheim 1987

HIRSCHI, A.: Berufswahltheorien – Entwicklung und Stand der Diskussion. [Theories behind career choices – development and focus of the discussion]. In: BRÜGGEMANN, T.; RAHN, S. (eds.): Berufsorientierung [Career orientation]. Münster 2013, pp. 27–41

MATTHES, S. et al.: Die Entwicklung des Ausbildungsmarktes im Jahr 2015. [The development of the education and training market in 2015]. Bonn 2016 – URL: www.bibb.de/ausbildungsmarkt2015 (retrieved: 29.03.2016)

SCHNITZLER, A.; GRANATO, M.: L’orientation scolaire et professionnelle – un choix idéaliste ou réaliste? Les aspirations éducatives des jeunes à la fin de leur scolarité à la lumière des influences personnelles et contextuelles. [Academic and vocational orientation – an idealistic or realistic choice? Educational aspirations of young people upon finishing school in light of personal and contextual influences]. In: BOUDESSEUL, G. (ed.): Alternance et professionnalisation: des atouts pour les parcours des jeunes et les carrières? [Sandwich courses and professionalisation: are these beneficial for the life choices and career pathways of young people?] (Relief 50). Marseille 2015, pp. 195–204

ANNALISA SCHNITZLER

Research Associate in the “Competence development” Division at BIBB

MONA GRANATO

Dr., Research Associate in the “Competence development” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 3/2016): Martin Kelsey, Global SprachTeam, Berlin

-

1

Cf. www.bibb.de/de/8475.php (retrieved: 29.03.2016)

-

2

For more information on those who changed their mind in the opposite direction, i.e. those who initially wanted to stay at school but ultimately favoured the education and training route, cf. SCHNITZLER/GRANATO 2015.

-

3

Cf. www2.bibb.de/bibbtools/de/ssl/dapro.php?proj=7.8.142 (retrieved: 23.02.2016)