Opportunities and challenges posed by the early integration of refugees

Interview with Prof. Dr. Christine Langenfeld, Chairwoman of the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration

The huge number of people fleeing regions affected by civil war and seeking refuge in Europe presents enormous challenges for countries which receive them. Asylum policy in Germany has undergone a transformation when compared to the mid-1990s. For refugees with good prospects of remaining, the focus is now on integrating them into society, education and training, and employment as quickly as possible. How can we do this? Which hurdles must be overcome, and which state and civil society institutions must respond?

CHRISTINE LANGENFELD

Christine Langenfeld has been chairwoman of the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration (SVR) since 2012. She is a lawyer and has been part of the independent and interdisciplinary expert body since it was established in 2009.

The SVR comments on policy-making issues relating to integration and migration and provides practical policy advice in this area. The Expert Council is based on an initiative of the Stiftung Mercator and the Volkswagen Foundation and is supported by seven large foundations.

Christine Langenfeld is a Professor of Public Law and Director of the Department of State Law at the Georg-August-University of Göttingen. Her fields of expertise include European law and the European Convention of Human Rights, integration and migration law and education law.

BWP: The rapid integration of refugees is the guiding principle of German integration policy. Have legislators done enough in this respect?

Langenfeld: It has now been a year since the paradigm shift towards early integration in the area of labour migration, made some years ago, has also applied to refugees with good prospects of permanent residency. There is cross party-agreement regarding this. The early integration concept aims to avoid the errors made in the treatment of so-called ‘guest workers’ in the 60s and 70s in Germany. No German language or integration courses were available at that time. This made it difficult for migrants and their families to settle in German society. The repercussions of this policy are still being felt today.

BWP: How are things changing now?

Langenfeld: Over the last twelve months, refugees have received support with their entry into society right from the start if it is expected that they will be recognized as a refugee in Germany. This includes early access to the labour market and to vocational education and training. Even if the asylum process is ongoing, refugees with prospects of permanent residence are able to attend German language and integration courses covering the basics of German politics, culture and local values in addition to basic German language skills. Courses relevant to an occupation should therefore be given particular support in order to further facilitate professional integration. The Bundesagentur für Arbeit [Federal Employment Agency] has provided significant funds for this purpose. However, the expansion in the number of language courses offered still falls some way short of the increased demand.

BWP: How should the changes in law be assessed regarding training and employment opportunities for refugees?

Langenfeld: An important new regulation is that since November 2014, applicants for asylum have the opportunity to work after three months of residency. This does not apply to asylum applicants from so-called safe countries of origin. However, a priority review is required prior to starting employment, i.e. the Bundesagentur für Arbeit only grants approval if there is no other suitable applicant for the position available. The priority review ceases to apply following residency of 15 months. This is dispensed with right from the start for refugees who are starting training. This is a good thing. A general suspension of the priority review for refugees with prospects of permanent residence is also being discussed. However, with all that said, we must be aware that entering the labour market too early may also mean that qualification activities and language learning is delayed. Evidence shows that young refugees quit education and training in order to earn money quickly. This is neither in the long-term interests of refugees or society.

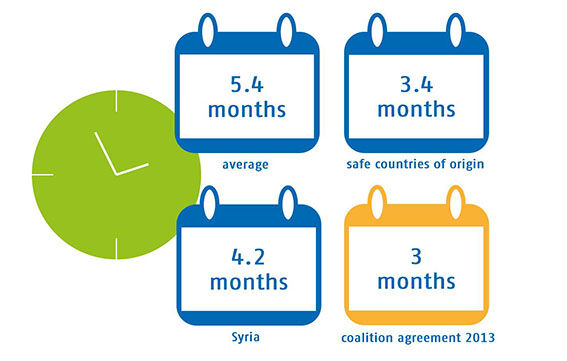

Figure 1: Duration of asylum procedure

BWP: Let's take a look at what is happening in practice: A sticking point is how long the asylum procedure takes. Can the problem of long processing times be resolved simply with more personnel, or are technical simplifications to the procedure conceivable?

Langenfeld: An increase in personnel is of course the key to speeding up the asylum procedure. And the faster the procedure is completed, the sooner the refugees can really focus on settling properly in Germany. This will also support integration. Every effort is currently being made at the BAMF, Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge [Federal Office for Migration and Refugees], to appoint new personnel.

The asylum procedure is also protracted because, basically, every application needs to be checked individually. This must also remain the case in principal. In this context, however, options exist for speeding up the process which legislators have made use of.

BWP: Which, for example?

Langenfeld: Accelerated procedures have been introduced for some particular groups of applicants with a high protection rate. This involves applicants from Syria, as well as Christians, Mandaeans and Yazadis from Iraq. Because the recognition rate for these groups is effectively 100 per cent they have had the option of stating their reasons for seeking asylum in writing instead of at a personal hearing. This has significantly reduced the length of the procedures overall, i.e to a few months. However, the individual test procedure was introduced once again for Syrian refugees in late autumn 2015 in order to ensure secure identification and that the need for protection is checked at an individual level. I can understand this. However, the result is that the procedures are extended. Everything possible must now therefore be done in order to shorten the procedure and get through the backlog of work at the BAMF.

On the other hand, a list of so-called safe countries of origin has been in existence since 1993. The view of legislators is that no political persecution or inhumane treatment takes place. This now also includes all Western Balkan countries which were, up until recently, the origin of 40 per cent of all refugees. Asylum applications from these states are processed as a priority. The recognition rate is virtually at zero per cent. But even here, each case must still be checked at an individual level. Whether or not the classification of the West Balkan states as ‘safe countries of origin’ has in fact contributed to shortening the procedure, is disputed; however, together with other steps, these measures have led to a drastic reduction in the influx from these states.

An additional aspect is important at this point. Up to now, it has not been possible for the BAMF, the Federal State authorities and the Bundesagentur für Arbeit to make the data collected about an individual refugee available to each other. This is due, amongst other things, to technical reasons. Modernization and coordination of the information technology of all Federal Government, Federal States and municipal authorities involved with refugees must be called for so that it's possible to work across the board with single electronic files. This would then avoid recording data about the same person on multiple occasions.

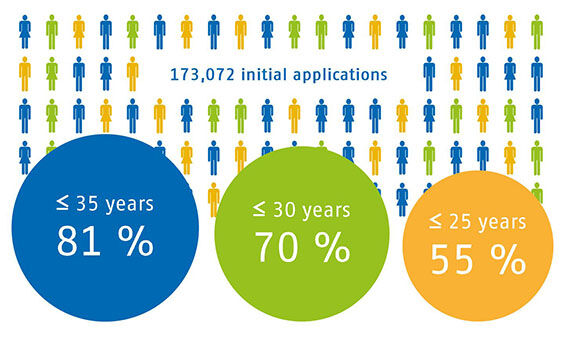

BWP: Over 55 per cent of asylum applicants in 2015 were under 25 years of age. Many of these are highly motivated and willing to learn. How can the education and training system be made ready to receive these young people?

Langenfeld: The deciding factor ultimately is that children are able to go to school as early as possible and learn the language. However the shortage of specialist training teachers is a problem. Not enough teachers are trained to teach German as a second language and to deal with traumatised pupils in school. This is where relevant advanced vocational training offers need to be created. And far greater emphasis must be placed on the subject area of German as a second language in teacher training.

Figure 2: Age structure of asylum applicants in 2014

BWP: Are there approaches in language development which might serve as good examples in your view?

Langenfeld: A great example is the Rhineland-Palatinate ten-point-plan for language development in schools. Additional funding running into the millions has been provided since the start of the year for holiday language courses, homework support and more than 150 cross-school intensive German-language courses. These intensive courses are run with the support of local adult education centres and church communities. An important aim of the ten-point-plan is also to improve the supply of teaching staff to reception centres.

BWP: And what is the current situation in vocational education and training?

Langenfeld: Much has already been done in vocational education and training in order to qualify young refugees for the world of work. In Bavaria, for example, asylum applicants and refugees are being prepared at 95 vocational school sites over two years for the company-based period of training. The Städtische Berufsschule zur Berufsvorbereitung [City Vocational School for Career Preparation] in Munich is regarded as a pioneer in this area. It has been offering a specialist pre-vocational training year since 2011 for young refugees who are no longer of compulsory school age and cannot find a training place. Business has also been very active already: Some companies have created additional work placements and training positions for refugees. One example of this is Siemens: Here a work placement programme has been started which aims to prepare up to 100 refugees at several locations for company-based education and training. The interns receive the usual pay and a personal point of contact on-site whose job it is to support them in their day-to-day work at the company. These initiatives are a positive start, although there needs to be an overall increase in the number of training places and work placements. With all that said, we must ensure that young refugees and German young people are not forced to compete against each other when training places and work placements are allocated. We therefore need companies to create additional training places and work placements.

BWP: Many companies are anxious about making such investments – particularly when prospects of permanent residence are uncertain.

Langenfeld: Legislators have taken an important step here: If an asylum applicant begins company-based education and training, completion of this education and training is guaranteed, at least in principle, even if there is a negative outcome to the asylum procedure. Unfortunately, this is not yet properly understood by training companies in many cases. The Chambers in particular need to inform their members accordingly. There is nothing preventing recruitment once education and training has been completed. However, this rule currently only applies if training is started before the age of 21. This age limit should be raised or even removed entirely. And following completion of training, young skilled workers should be given the chance to search for employment for a specified period of time.

“If an asylum applicant begins company-based education and training, completion of this education and training is guaranteed, even if there is a negative outcome to the asylum procedure.”

BWP: Vocational education and training therefore has an important role to play in the integration process?

Langenfeld: Absolutely! Because it allows refugees to earn a living for themselves. The contacts in the company make it easier to learn German and develop personal contacts. This contributes above all to the recognition of refugees as fully valued members of society. The earliest possible professional integration of refugees also reduces the financial burden on the state. This then encourages acceptance of the influx of refugees among the population. The potential in terms of workers and trainees is also of real interest to business. Here, the influx of young refugees in particular is regarded as an opportunity, but at the same time as a major challenge.

BWP: Is it sensible to combine asylum and labour migration policy?

Langenfeld: We really have to watch out and must not mix up these two migration routes. Those seeking and finding protection in Germany for humanitarian reasons and those fleeing danger in their country of origin receive protection regardless of whether they are young or old, healthy or ill or whether they have specialist education and training or not. It does not depend on the “usefulness” of refugees for the German labour market. And it is also not dependent on whether and how much refugees contribute to alleviating the consequences of demographic change on the labour market and the social security systems in Germany.

Emphasizing the humanitarian nature of refugee migration will not prevent policy makers from exploring the potential which exists for Germany in the migration of refugees – on the contrary, they have to do this – and must do all they can to ensure that this potential is increased. This is where the concept of early integration of refugees with good prospects of permanent residency comes in.

BWP: The SVR called for existing qualifications to be ascertained more quickly than previously and for red tape involved in the recognition of vocational qualifications to be removed. Where do you see specific need for improvement?

Langenfeld: To clarify: It is possible to work in many occupations even without recognition of the vocational qualification. In some cases and due to statutory requirements, for example in healthcare occupations, recognition is needed in order to be able to even practice the occupation. Recognition also increases the likelihood of success on the job market, because businesses can clearly see the knowledge the applicant has. However, authorities face significant challenges in determining and recognising the vocational qualifications of refugees.

BWP: What are these and how can we respond?

Langenfeld: It is often no longer possible for documents to be submitted once a person has fled their country of origin. But this does not mean that people do not have vocational skills. Having said that, a lack of knowledge exists regarding education and training systems in the countries of origin. What does an intermediate school leaving certificate from this country represent? Does a developed vocational education and training system exist, or is there a reliance on vocational experience? What job descriptions exist? All this makes it significantly more difficult to determine and assess the existing qualifications. In this case, much greater use must be made of interviews, work placement and the preparation of a qualification profile – so-called profiling. At this point a new form of flexibility is needed in how competencies can be validated and further developed. Recognition of partial qualifications and “on the job” qualifications should increasingly be made possible. In the course of this we must ensure that a lowering of quality standards for specialist qualifications does not occur.

“In the assessment of qualifications, a new flexibility is needed in how competencies can be validated and further developed.”

BWP: The influx of refugees not only changes the working and professional environment, but also society as a whole. What can be done by both policy makers and by civil society?

Langenfeld: By taking in people in need, Germany has achieved something great – and this is still regarded as such by the vast majority of the population. In terms of refugee integration, a realistic picture has now emerged politically and in wider society. Many understand the work involved will take generations, but that if it is approached correctly, it will also prove to have been an opportunity for Germany. Labour market integration is important, but it is not the end result. It is about making refugees familiar with the values which govern living together in Germany on the basis of our constitution.

BWP: The population also remains fearful in terms of the religious background of most refugees. How do we deal with this?

Langenfeld: The level of openness in the population – and the tendency to identify as ‘welcoming culture’ – remains large. However, surveys also show that a degree of concern exists in the population over whether Germany can cope with the large numbers of refugees despite its economic strength. At the same time, the number of violent attacks on refugee accommodation is increasing; right-wing rhetoric is being used to stir up feelings against refugees at protest rallies. The terror attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015 serve to further reinforce this tendency. Policy makers must react to this and provide answers to prevent fears in the population from growing and being linked to the immigration of refugees.

BWP: What might these answers be?

Langenfeld: The key factor is whether through agreements at national and also European level, politics is able to quickly arrive at controls and limitations on the immigration of refugees, and to achieve a sensible and resolute integration policy combining a sense of reality, patience and trust. Fears over new disputes regarding distribution should also be resolved: there is no scientific evidence that refugees drive out local German workers. At the same time, debates such as those about the suspension of the minimum wage should be conducted with great caution. Otherwise the impression will be created that social achievements are suddenly being thrown overboard due to the refugee influx. Policy makers must make sure people do not get the feeling they are losing out. Everybody must therefore stand to benefit, for example, from measures such as house building. Anything else would endanger the acceptance of refugee immigration which has existed up to now among the population.

(Christiane Jäger conducted the interview in December 2015)

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 1/2016): Martin Lee, Global SprachTeam, Berlin