Recognizing vocational qualifications of refugees – examples from “Prototyping Transfer”

Carolin Böse, Dinara Tusarinow, Tom Wünsche

The Recognition Act which entered into force on 1 April 2012 aims to provide better employment opportunities in training occupations for people with foreign vocational qualifications. This option is also of interest for refugees, many of whom were unable to bring with them the relevant documents needed for the vocational qualification to be recognised, such as a diploma or employment reference. However, under certain circumstances, a recognition procedure may also be carried out without documents by means of skills analysis. The article examines this option which is enshrined in the Professional Qualifications Assessment Act (BQFG), and presents initial experiences of its implementation.

Recognition despite missing or incomplete documents

During 2014, Alaa Kheralah aged 33 and from Syria, applied for asylum in Germany. He had previously completed training as a dental technician in Jordan and following this he managed his own dental technician laboratory in Damascus. Civil war then forced him to leave his home country. He created a new life for himself in Ludwigshafen and wanted to work here in the occupation he had trained for as soon as possible. All the requirements needed to apply for recognition of vocational qualifications were therefore in place – completed vocational education and training and the intention to work professionally in Germany. Mr Kheralah had actually brought the certificates relating to his qualification with him to Germany. However, in order to compare the German and Jordanian dental technician training, the competent authority needed additional information about specific training content, but Mr Kheralah was unable to provide any written evidence of this.

He experienced what many refugees go through who are no longer able to provide the evidence required having had to escape from war-affected regions. Even if the certificates are available, the competent authorities often need additional information in order to be able to compare the content of education and training obtained in Germany and overseas.

It is often impossible to obtain this information if war is raging in the training countries or if the applicants have suffered political persecution. The BQFG provides options even in these cases: Applicants may provide evidence of vocational competencies which cannot be demonstrated via written evidence by means of so-called “other appropriate procedures” (cf. Section 14 of the BQFG and Section 50a (4) of the Crafts and Trades Regulation Code) – for example, by means of specialist interview or work sampling (an identical paragraph has been adopted in each case in the Federal States’ recognition laws). This procedure is described as “skills analysis” (Qualifikationsanalyse) in the following (cf. OEHME 2012). This allows an application for the recognition of foreign professional qualifications regardless of nationality and residence permit. This means that no specific recognition regulations are necessary for refugees or asylum seekers, but instead that the regulations already in place are sufficient.1 The skills analysis is an assessment of competency and is not a test within the meaning of the Vocational Training Act (BBIG) and the Crafts and Trades Regulation Code (HwO) (cf. KRAMER/WITT 2012). It is therefore based on other procedural standards than an external examination, for example.

Higher number of recognitions with skills analyses using Prototyping Transfer

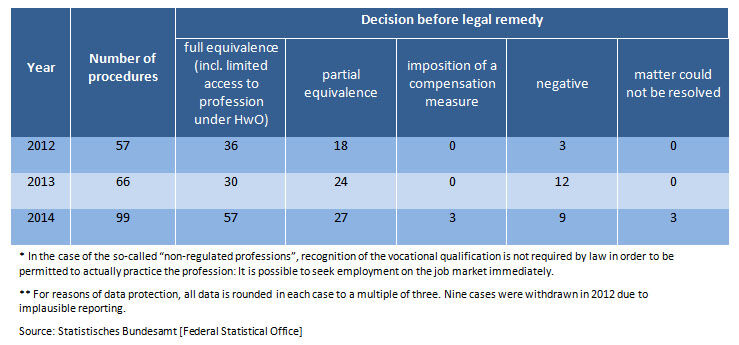

As the number of immigrants increases, there has been a general rise in level of interest and demand for recognition of foreign professional qualifications and therefore also in recognition options available in the event of missing documents. Up to now the annual number of skills analyses completed and reported as part of official statistics has risen gradually (cf. Tab). The reference occupations featuring most frequently in these procedures were “motor vehicle mechatronics technician”, “electronics technician” and “joiner”.

Table: Numbers and decisions in procedures for non-regulated professions* and regulated master craftsman occupations, decisions for which were made using the ‘other suitable procedures’ option**

As the table illustrates, the number of procedures completed so far is very small. A reason for the current reluctance is a lack of familiarity with skills analyses among competent authorities and counselling organisations. Some authorities are afraid of the perceived high level of work which a skills analysis requires as this involves the need to get hold of experts and for tools and performance requirements to be adapted to the individual case. However, competent authorities who have already gained experience identify a reduction in workload because, according to them, it is largely only the initial development which involves substantial work.

The three year project “Prototyping Transfer – recognition of professional and vocational qualifications via skills analyses” was launched in January 2015 with the aim of increasing the number of skills analyses. The project is financed by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) [Federal Ministry of Education and Research] and is based on the procedural standard developed in the previous “Prototyping” project. The project is being coordinated by the BIBB.

Procedural standard for prototyping

The previous prototyping project (August 2011 to January 2014) was coordinated by the Westdeutscher Handwerkskammertag (WHKT) [West German Chamber of Crafts Council] and academic support was provided by the Forschungsinstitut für Berufsbildung im Handwerk (FBH) [Research Institute for Vocational Training in the Crafts Sector] at Cologne University. The prototype procedural standards and support developed as part of this is available to download: www.anerkennung-in-deutschland.de/html/de/qualifikationsanalyse.php.

Prototyping is being implemented by six project partners. These are the Westdeutscher Handwerkskammertag, IHK FOSA [Foreign Skills Approval, a public sector association of 77 Chambers of Industry and Commerce for the assessment of equivalence in professional qualifications], the Chamber of Craft Trades for Mannheim and Hamburg and the Chamber of Industry and Commerce for Cologne and Munich. They are working together to improve the awareness of qualification analyses, to inform other competent authorities and counselling organisations regarding options and to provide specific support with implementation. Materials and training for employees in the competent authorities is being provided for this purpose. Individual advice is also available. As the project proceeds, the intention is also to put together completed skills analyses and performance requirements, and where required to make these available to other competent authorities. This measure is intended to significantly reduce the level of work required for subsequent skills analyses in the same occupations.

The costs of a skills analysis varies according to duration, and the tool and where applicable necessary workshops and/or material selected (cf. BÖSE/SCHREIBER/LEWALDER 2014). In individual cases and once checks have been made, Prototyping Transfer offers to meet the costs of completing a skills analysis if it is shown that these will not be met by labour administration under the Social Security Code II/III. The special fund for financing skills analyses within the scope of the Prototyping Transfer project is administered by the WHKT. Chambers which are not a project partner in Prototyping Transfer may approach the WHKT directly if they have questions.

The competent authority for Alaa Kheralah’s recognition procedure is the Mannheim Chamber of Craft Trades, project partner in Prototyping Transfer. They check the recognition application and offer to verify Mr Kheralah’s occupational competencies for which no documentary proof is available, by means of skills analysis. He was invited to undertake trial work over five days in a dental technician laboratory observed by two experts. As part of the skills analysis, Mr Kheralah was required to work in a range of tasks and in the end his professional qualification was assessed as being fully equivalent. He started working in a dental laboratory a few months ago and he attends a German course in the afternoons. Financing of Mr Kheralah’s skills analysis was made possible through the project’s special fund.

Focus on refugees

The express intention of legislators was to use recognition of foreign professional qualifications to also increase the likelihood of success in the labour market for refugees. In the explanations to accompany the BMBF Recognition Act it states that:

Section 18a of the Residence Act, recently added by the Labour Migration Control Act of 2009, [makes it possible] for persons resident on a discretionary basis to receive a residence permit if they find employment appropriate to their qualification. The initiation of a recognition procedure for persons resident on a discretionary basis helps to enhance the effectiveness of this regulation, introduced in the interests of meeting the demand for skilled workers” (BMBF 2012).

Since the residence permit is not a requirement for a recognition application, no information is recorded as part of official statistics about this. Therefore, based on the current data available, it is not possible to state how often refugees make use of the options provided under the Recognition Act.

Within the scope of the Prototyping Transfer project, project partners have collected, where possible, information regarding residency status of applicants for skills analyses completed. A detailed look at the first twenty skills analyses completed shows that four individuals held a residence permit under Section 22-26 of the Residence Act (Residence for reasons of international law, for humanitarian or political reasons). No information was available for three of the individuals, and the other thirteen had another residence permit or had German nationality at the time of the skills analysis.

These skills analyses still included statements regarding the nature of the missing documents. In virtually all cases it was not possible to submit relevant information regarding content and the general framework of the training for the purpose of determining equivalence. In addition, in four cases, documents about the professional qualification itself were missing and in three cases no meaningful evidence regarding professional experience was available.

Most project partners are currently reporting that enquires are being received increasingly by people from Afghanistan, Syria, Iran or Eritrea. It may be supposed – even without the residency permit information – that the reasons for leaving the countries of origin relate to the asylum process.

All project partners assume that, in future, a continued increasing interest in skills analyses is to be expected, in particular from recent immigrants. It is therefore important to actively create access for refugees and to clarify the options under law for the recognition of a foreign professional qualification and the requirements which must be met for this. This strategy is already being followed by competent authorities, for example, in refugee organisations or on ESF-BAMF language courses.

Pragmatic solutions where knowledge of the German language is inadequate

Everyone agrees that language skills are a basic requirement for integration. Ongoing expansion of the provision of integration and occupation-related language courses is therefore fundamentally important.

The training regulations for the training occupations in the dual system contain no specific requirements for language skills which means language level testing cannot also form a component of the equivalence check. A reoccurring topic of discussion is the fact that “company-based communication” is noted as a skill to be delivered in most training regulations. This includes, for example, being able to “conduct discussions in a manner appropriate for the situation” or “explain issues” (Federal Law Gazette 2013, p. 1594). These formulations imply requirements in terms of German language skills, but these are not explicitly set out.

On the other hand, in the area of dual education and training occupations in general, no evidence of language skills is required from individuals who can submit their documentation in full. Ultimately, companies decide on the extent of German language skills employees need when they start, and what is required of them, in the course of the recruitment process.

If German language skills are not yet sufficient, pragmatic solutions must be found if refugees without documentation are to benefit from the opportunity provided by skills analyses. This is in line with the objective of ensuring the integration of new immigrants both professionally and into society occurs as quickly as possible. Such measures do not exclude the systematic acquisition of (additional) German language skills in parallel to the recognition procedure.

The project partners in the Prototyping Transfer project have agreed that, as far as possible, the skills analysis should be conducted in the German language. However, additional aids may be used where required, e.g dictionaries. Translators may also be called in to help explain the tasks. In the first twenty skills analyses completed, a dictionary was used in two cases and in one instance, a translator was used. It also makes sense to prepare a bilingual glossary containing relevant specialist terms in occupations which are in demand. On the one hand, this would support the learning of important specialist terms and, on the other, translators would not be required. This task is being worked on as part of the project and the necessary preparation work is already under way.

Implementation challenges

It is important, across all occupations, to have a uniform application of the procedures at a national level in the event of missing documents. The objective of the Prototyping Transfer project is therefore to inform competent authorities so that they understand and apply the range of possible procedures in the event of missing documents. The challenge is to develop a shared pool of expertise and knowledge of completed skills analyses, ideally involving all chambers, in order to benefit from previous experiences. This reduces the work involved in implementation and leads to uniform procedures.

Up to now, only very few skills analyses have been completed among the Chambers of Industry and Commerce. The IHK FOSA actually completed the equivalence check for virtually all Chambers of Industry and Commerce, however the respective regional Chamber is responsible for implementation of the skills analysis. The regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce are presumably therefore more reluctant when advising on the skills analysis as it is ultimately the IHK FOSA which decides whether or not to conduct the analysis. It is important therefore to continue to intensify the dialogue between the local Chambers of Industry and Commerce and the IHK FOSA and to create transparency in terms of the decision-making criteria.

Both uniform and, in particular sustainable organisational and funding options must be found for the skills analyses, particularly with regard to the language skills required, in order that individuals currently seeking asylum in Germany can benefit from the regulations.

This should be a shared objective among stakeholders both in terms of securing a skilled workforce on the one hand, and on the other in terms of the rapid integration of refugees professionally and in society.

-

1

Healthcare occupations also have recognition regulations for missing documents. In these cases, level of knowledge equivalence must be demonstrated by means of an assessment test.

Literature

BÖSE, C.; LEWALDER, A.; SCHREIBER, D.: Die Rolle formaler, non-formaler und informeller Lernergebnisse im Anerkennungsgesetz. [The role of formal, non-formal and informal learning outcomes in the Recognition Act] In: BWP 43 (2014) 5, p. 30-33 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/id/7433 (retrieved 08.12.2015)

BUNDESGESETZBLATT: Verordnung über die Berufsausbildung zum Kraftfahrzeugmechatroniker und zur Kraftfahrzeugmechatronikerin [Regulation on vocational training as motor vehicle mechatronics technicians]. 2013 Part I No. 29, published in Bonn on 20 June 2013

BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR BILDUNG UND FORSCHUNG (BMBF) Erläuterungen zum Anerkennungsgesetz des Bundes [Explanations Accompanying the Federal Government Recognition Act]. Bonn/Berlin 2012

KRAMER, B.; WITT, D.: Die Bewertung ausländischer Berufsqualifikationen und anknüpfende Qualifizierungsangebote im Handwerk [The assessment of foreign professional qualifications and related qualification offers in the skilled crafts]. In: BWP 41 (2012) 5, p. 29-31 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/id/6940 (retrieved 08.12.2015)

OEHME, A.: PROTOTYPING – ein Verbundprojekt zur Qualifikationsanalyse [PROTOTYPING – a joint project for skillsskills analysis analysis]. In: BWP 41 (2012) 5, p. 31-32 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/bwp/show/id/6939 (retrieved 08.12.2015)

CAROLIN BÖSE

Research associate in the “Recognition of Foreign Professional Qualifications” Division at BIBB

DINARA TUSARINOW

Research associate in the “Recognition of Foreign Professional Qualifications” Division at BIBB

TOM WÜNSCHE

Research associate in the “Qualifications, Occupational Integration and Employment” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 1/2016): Martin Lee, Global SprachTeam, Berlin