Does the introduction of a minimum wage reduce the incentives for commencing apprenticeship training?

Harald Pfeifer, Günter Walden, Felix Wenzelmann

The planned introduction of a statutory minimum wage in the German economy is currently leading to intensive discussions regarding the consequences this would have for vocational education and training. The article tries to assess possible effects of introducing a minimum wage on initial education and training.

The debate on the minimum wage and possible effects on initial education and training

The coalition agreement of the new German government stipulates the introduction of a statutory minimum wage. An amount of 8.50 euros is proposed. At present about 15 per cent of all employees in Germany receive wages below the minimum wage; in East Germany the figure is approximately one in four (cf. BRAUTZSCH/ SCHULTZ 2013, BRENKE 2014). The extension of the minimum wage to apprentices seems to be no longer a subject of discussion due to the expected negative effects on the willingness of companies to provide training.

From the viewpoint of the companies this would lead to a substantial increase in apprenticeship training costs, since wage costs constitute a considerable part of the costs of training (cf. SCHÖNFELD et al. 2010).

However, a subject of current discussion is the question of whether the introduction of a minimum wage for employees could also have negative effects on apprenticeship training. There are concerns that young people will consider it more attractive to renounce apprenticeships and instead take up jobs as unskilled workers at the minimum wage. Some political authorities therefore demand the creation of exceptions for persons below the age of 25.1

This article contains a brief assessment of the possible effects the introduction of a minimum wage might have on the incentives for young people to commence apprenticeships. A quick glance will also be taken at the question of to what extent the attractiveness of training for the companies could be affected. The fact that there have been so far no empirical findings regarding the influence of introducing a minimum wage on apprenticeship training in Germany must be taken into account.2An assessment of possible effects is therefore primarily based on theoretical foundations and plausibility considerations.

The introduction of a minimum wage from the viewpoint of economic theory

According to economic theory, introducing a minimum wage for employees would increase the opportunity costs of training for the apprentices if the training allowances are not raised at the same rate. The opportunity costs of training are determined by the difference between the training pay and the wages attainable as an unskilled worker on the labour market. They indicate the financial benefits the apprentices would forego during their training.

If the wages of unskilled workers rose as a consequence of the introduction of a minimum wage, the opportunity costs of training would rise as well. If we therefore only consider the phase of apprenticeship training, this training would become less attractive for young adults after the introduction of a minimum wage.

Model calculations carried out at the BIBB on the basis of data on costs and benefits of apprenticeship training show that raising the minimum wage would increase the opportunity costs by approximately 4,500 euros on average for the entire period of training (cf. box on model calculations).

However, since the decision for or against participating in an apprenticeship is also based on reflections on the longer-term education returns, a person behaving rationally would consider the difference between the wage attainable as an unskilled worker and the wage attainable as a trained skilled worker as the decisive factor.

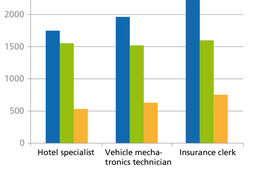

The figure on page 50 identifies the differences between training pay and wages for unskilled and skilled workers (for a differentiation by selected company structural characteristics cf. BEICHT/WALDEN 2012).

The figure shows that e.g. for vehicle mechatronics technicians and insurance clerks (but not for hotel specialists) the gap between the wages of skilled workers and the wages of unskilled workers is so large that the increase in opportunity costs to the amount of 4,500 euros can be quickly regained by working as a skilled worker after successful completion of training. Furthermore, current findings of the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) confirm that acquisition of a vocational qualification leads to long-term income advantages for employees (cf. SCHMILLEN/ STUBER 2014).

Model calculation on the effects of the minimum wage

The model calculation on the effects of a minimum wage on training incentives is carried out using the data from the 2007 BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey.

The first step is to adjust the wages, training allowances and prices surveyed to the year 2012.

The adjusted values can then be used to recalculate both the wage differences and the costs and benefits of training at the company level (for further information on the calculations cf. SCHÖNFELD et al. 2010).

In a second step, those wages of unskilled and skilled workers which lie below 8.50 euros per hour are replaced by the minimum wage.

The opportunity costs additionally incurred by the apprentices due to the minimum wage result from the difference between the opportunity costs hitherto incurred (without minimum wage) and the newly calculated opportunity costs (with minimum wage).

The effects of the minimum wage on the company cost-benefit ratio can also be simulated using the adjusted data.

On average, the productive activities of the apprentices generate a higher benefit for the companies because having to make up for the work of the apprentices by employing unskilled workers would be more costly for the companies.

Reduced training incentives due to small wage differences

Changes in the structure of incentives could arise mainly in those sectors and occupations where the education returns are already small and where the increased opportunity costs would therefore have a decisive influence on the individual cost-benefit ratio. These are primarily sectors and occupations with only minor differences between the wages of unskilled and skilled labour. One example would be the occupations in the catering sector (cf. figure).

The results of the model calculations also indicate that the wage differences in certain sectors and occupations would decrease after the introduction of the minimum wage, presumably leading to correspondingly decreased education returns as well.3

The decisive factor, however, is how the wage differences between skilled and unskilled workers in the respective sectors and occupations will develop in the long term. The smaller these differences are, the smaller are naturally the incentives for commencing an apprenticeship.

Unfavourable employment opportunities for unskilled workers

Another key question is whether the alternative strategy of taking up employment as unskilled workers at the higher minimum wage is in fact feasible for the young people. If the introduction of the minimum wage were to lead, for instance, to an increased labour supply in the respective sector (e.g. due to the involvement of the previously "inactive" labour force) and, at the same time, to a decreased labour demand (owing to the higher wage costs incurred by the employers), this would reduce young people's chances of finding any job at all as unskilled workers at the minimum wage.

If young adults were to take this growing risk of unemployment into account in their cost-benefit analysis, initial vocational education and training would presumably become more attractive again. In addition, the training pay can also be expected to increase in the medium term in sectors in which the introduction of the minimum wage significantly raises the wage rate, since wage adjustments for employees agreed on in collective bargaining are often accompanied by corresponding adjustments in trainee pay. Such an adjustment would counteract the increased opportunity costs discussed above.

Training does not depend only on money

The education economic arguments presuppose that apprentices make their decisions rationally and exclusively based on cost and benefit considerations. However, it can be assumed that young adults do not make their educational decisions solely on the basis of financial criteria. Even though BIBB surveys show that approximately 70 per cent of all apprentices attach importance to earning a lot of money even during their training (cf. BEICHT/KREWERTH 2010), the social and family context also plays an important role.

Attractiveness of training from the viewpoint of the companies

From the companies' viewpoint, the introduction of a minimum wage for employees could increase the attractiveness of training (cf. ACEMOGLU/PISCHKE 1999). The work so far performed by unskilled workers, for example, could be more gainfully integrated into the training activities. In this regard, the BIBB model calculations suggest that the value of the productive performance of the apprentices would increase by about five per cent if a minimum wage were introduced (cf. method box, p. 49).

Empirical studies carried out in the United Kingdom, where a minimum wage was first introduced in 1999, show that the companies invest in the initial and continuing education and training of their employees to the same degree (cf. ARULAMPALAM et al. 2004) or even to a higher degree (cf. METCALF 2004).

These empirical studies, however, can be applied only to a limited extent to the German case of the dual system of apprenticeship training.

Summary

The introduction of a minimum wage would most likely reduce the incentives for commencing apprenticeship training particularly in those occupations and sectors where the wage differences between skilled and unskilled workers are already minimal or will significantly decrease due to the introduction of the minimum wage.

Special attention must be paid in the future to the long-term development of wage differences between these groups of employees, since the returns of apprenticeship training depend on it. From the company point of view, on the other hand, increased economic attractiveness of training is to be expected.

As soon as initial data on the introduction of the minimum wage have been gathered, the observable effects should be analysed scientifically in order to improve the foundations for a further optimisation of the relevant legal provisions.

Literature

ACEMOGLU, D.; PISCHKE, J.-S.: The structure of wages and investment in general training. In: Journal of Political Economy 107 (1999) 3, pp. 539-572

ARULAMPALAM, W.; BOOTH, A. L.; BRYAN, M. L.: Training and the new minimum wage. In: The Economic Journal 114 (2004) 494, pp. C87-C94

BEICHT, U.; KREWERTH, A.: Geld spielt eine Rolle! Sind Auszubildende mit ihrer Vergütung zufrieden? In: BIBB Report 14/2010

BEICHT, U.; WALDEN, G.: Ausbildungsvergütungen in Deutschland als Ausbildungsbeihilfe oder als Arbeitsentgelt. In: WSI-Mitteilungen 5/2012, pp. 338-349

BRAUTZSCH, H.-U.; SCHULTZ, B.: Im Fokus: Mindestlohn von 8,50 Euro: Wie viele verdienen weniger, und in welchen Branchen arbeiten sie? IWH press release 19/2013

BRENKE, K.: Mindestlohn: Zahl der anspruchsberechtigten Arbeitnehmer wird weit unter fünf Millionen liegen. In: DIW Wochenbericht 5/2014, pp. 71-77

METCALF, D.: The impact of the national minimum wage on the pay distribution, employment and training. In: The Economic Journal 114 (2004) 494, pp. C84-C86

SCHMILLEN, A.; STÜBER, H.: Bildung lohnt sich ein Leben lang. In: IAB Kurzbericht 1/2014

SCHÖNFELD, G. et al.: Kosten und Nutzen der dualen Ausbildung aus Sicht der Betriebe. Ergebnisse der vierten BIBB-Kosten-Nutzen-Erhebung. Bielefeld 2010

HARALD PFEIFER

Research associate in the “Costs, Benefits, Financing” Division at BIBB

GÜNTER WALDEN

Head of the “Sociology and Economics of Vocational Education and Training” Department at BIBB

FELIX WENZELMANN

Research associate in the “Costs, Benefits, Financing” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 2/2014): Paul David Doherty, Global Sprachteam Berlin

-

1

Cf. e.g. "Anspruch auf den Mindestlohn nur mit Ausbildung", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of 4 February 2014, p. 10.

-

2

Empirical studies exist primarily for the United States and the United Kingdom. They mostly deal with the influence of minimum wages on continuing vocational training.

-

3

The data used for this article represent company averages and have therefore only limited utility for calculating the changes in wage differences.