Trainers as stakeholders in the structuring of transition

Ursula Bylinski

The main focus of the BIBB research project "Professionalism requirements of educational staff at the transition from school to the world of work"1 was on the question of which competences are necessary to structure transition in a successful manner. One of the results to emerge is that multi-professional cooperation on the part of the specialists involved is of particular significance for the establishment of "educational chains". The present article concentrates on the subjective view of the trainers with regard to their professional practices and understanding of the role they play in order to illustrate the perspective they bring to the cooperation.

A qualitative study

The aim was to use the action and requirements context of educational professionals as a basis to identify the competences required for targeted pedagogical action in the transitional system. Four sample groups of education and training staff were included. These were teachers at general schools (schools for pupils with learning difficulties, lower secondary level), vocational school teachers (school-based vocational preparation), special needs staff (school social work, educational support) and trainers (vocational orientation, vocational preparation, vocational education and training). Group discussions and individual interviews were conducted at eight locations with 57 persons, including 15 company representatives. 13 persons stated that they acted as a trainer (female=3, male=12), two were in a managerial role (for detailed information on research design and results, cf. BYLINSKI 2014).

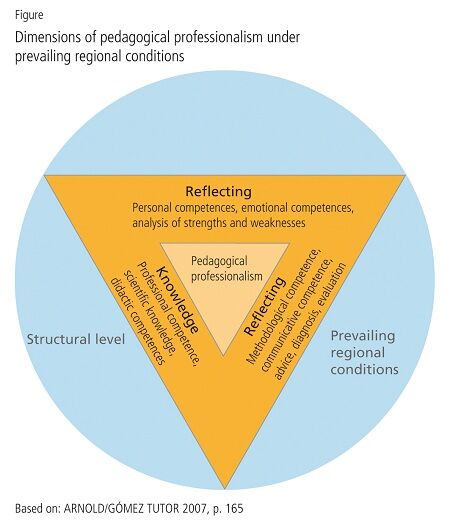

Taking the concept of reflexive pedagogical professionalisation (cf. ARNOLD/GÓMEZ TUTOR 2007, p. 164) as a basis, it was fundamental to the study that occupational competence is guided by three dimensions - knowledge, ability and reflection. Professional expertise is only created as a result of the interplay of these dimensions. This concept was expanded via integration into the prevailing regional conditions, i.e. into a joint action framework that is of significance to all four groups of educational professionals (cf. Figure).

Competences for successful structuring of the transition

The findings of the qualitative study show that structuring of the transition has led to a new quality of professionalism. Two areas of activity demand high requirements. These are individual assistance and (learning) support for young people on their way to the world of work, requiring the linking of educational stages), and secondly the networking and cooperation of institutions and stakeholders due to the fact that the complexity of the transitional system means that no institution is any longer able to meet the demands alone. It was possible to identify the following competences for pedagogical transitional action.

- Offering individual assistance and advice to young people requires competences relating to biographically oriented career pathway support, something which includes using the young person as the starting point for the design of pedagogical interventions (focus: the individual). In addition to this, competences relating to the subject-oriented structuring of learning processes or situations and for pedagogical action in heterogeneous leaning groups (focus: the group).

- Multi-professional cooperation requires intermediary competences (cf. WEINBERG 2004) in order to be able to act with and between the educational institutions involved (focus: the network) as well as intra-systemic and inter-systemic competences with regard to reaching agreement (focus: team work) for interdisciplinary cooperation within and outside the institutions.

Exploration of the field of activity and analytical evaluation of content (cf. MAYRING 2008) of the group discussions and individual interviews enabled both conducive general conditions and factors blocking multi-professional cooperation to be highlighted. Consideration of the practices of the individual education professionals is of particular relevance within this context because this subjective view is taken into and materially determines cooperation.

Trainers in the transition system

The trainers with whom individual interviews were conducted (female=1, male=7) were active in extra-school vocational preparation and in company-based vocational education and training. One trainer was a vocational preparation works instructor at a chamber of crafts and trades. Three trainers worked in their own craft trades companies (a car dealership, a painting and decorating firm and a butcher's), where some training was delegated to training staff. Two further trainers were training managers at a major company (a logistics provider operating nationally, public utilities/swimming pool operations). One respondent provided training in wholesale and retail, whilst another had taken on the role of an apprentice supervisor on a voluntary basis (hairdressers' guild). All trainers bring several years of occupational experience to the table, including within the transitional system.

Networking - greater transparency, coordination and support

The trainers consider networking to be indispensable to the same degree as the other respondents in order primarily to integrate disadvantaged young people into company-based training. The networking they carry out is initially in pursuit of their own interests. The main focus is on the acquisition of skilled workers, on the improvement of coordination processes and on taking advantage of support structures. Their networking usually relates to direct partners within vocational education and training - the chambers, the guilds, other companies providing training and the vocational schools. Training service providers have a role to play by providing socio-pedagogical support to young people with special needs or by taking over partial tasks within the training. The networking does not appear to be very systematic and structured.

The talk is frequency of "relationships" which facilitate agreements amongst one another. Each institution follows its own path in pursuit of its own respective objective. Coordinated joint action tends to be rare.

"The way that I see it is that the vocational school tends to go its own way in just the same way as the company. I wouldn't say that they oppose each other, it's just that each party goes along side-by-side rather than together, or not very much together." (GD-HL-AB-m-355-357).

The occasion for cooperation that tends to be bilateral in nature is mostly a specific problem situation with a young person or incidences of rule contraventions. Trainers expect a network to provide more information on support opportunities in order to intensify regional cooperation and reduce the burden on themselves.

The task of bringing the various stakeholders together and steering activities is assigned to local coordination.

Professional practices and understanding of the role

Looking at the way in which training staff understand their role makes clear the motivation for the establishment of cooperation and the perspective they bring to this cooperation.

The company and the occupation shape pedagogical activity

The pedagogical activity of the trainers is clearly located within a company reference framework and relates to the respective occupation in which they provide training. They believe young people to be "on the right road" once they have commenced vocational education and training which, in the interests of occupational socialisation (cf. LEMPERT 2009), also includes fostering personal development. They count it as a personal success if "[...] this trainee later becomes a specialist worker." (GD-HL-AB-m-97-357). Such an attitude evaluates the development of an occupational identity as the confirmation of their own work.

Although the profitability of the company is the main emphasis, particular value is attached to training which is of good quality. This is furnished with an external effect that helps create a positive image for the company. "As a public utility company, we do not particularly wish to be viewed as a bad training provider." (EI-LKL- AB-m-294). Trainers experience satisfaction if the quality of training is appreciated outside their own company. This is something for which they themselves are responsible. "Yes, he's been trained. He did an apprenticeship at company X. He's a 'good one'". (EI-HL-AB-m-97).

Training staff consider the company and the world of work to be a "contrast programme" to life at school. They equate vocational education and training with a "step into life" and view learning in a company context as an advantage for young people. "It's certainly tougher with us than at school. We may treat them with kid gloves a little bit, for the first two or three days, but after this we try to make it clear what makes working life tick. I find this very important." (EI-HH-AB-m-18). In their capacity as trainers, they are also seeking to set boundaries and use the vocational training to give young people guidance.

Commitment to vocational orientation and view of the young people

Because of falling numbers of applicants, companies are interested in work experience. This helps with staff acquisition and provides a direct impression of potential trainees. The attitude of the young people towards a practical placement is the crucial factor for trainers, even when making the initial selection. "Those who turn up very late and where we notice that they are just looking for somewhere to park themselves, [.] we prefer to give a chance to people who take things seriously." (EI-LKL-AB-m-60). Specific prior knowledge and occupational experience are particularly appreciated. Occupationally related holiday jobs or courses already completed are seen as professional aspiration.

The view of the young people is characterised by negative descriptions in many cases, and prior school learning is considered to be insufficient for vocational education and training. Nevertheless, trainers are inquisitive as to the causes of this and wish to gain more knowledge in order to be able to understand types of behaviour better. They have questions about the lifeworld of the young people and about their habits, attitudes, wishes and problems. "What kind of kids are we dealing with here [...], why do they have their baseball caps on the wrong way round, why do they have plugs in their ears?" (EI-HH-AB-m-199).

Trainees should fit in with the company culture and working atmosphere

The trainers highlight the fact that companies are perfectly prepared to recruit young people with special needs. However, they stress that work needs to be done to win over customers and journeymen and that in some cases young people meet with reservations. "There are customers, particularly amongst the well-off high-quality clientele that form part of our target group, who sometimes come to us and say 'Look here, [.], I don't want an apprentice'." (EI-HL-AB-m-4). Good organisational integration into company procedure is not the only significant factor when recruiting trainees. They also need to fit in with the company culture and atmosphere. "Success, at least as far as our firm is concerned, is 100 percent dependent on the working atmosphere. And the trainees form part of this working atmosphere. We are a team. And this involves give and take on a daily basis." (EI-HL-AB-m-16). This underlines the educational remit of familiarising the young people with company customs and imparting values and communicative rules to them.

Personal experiences and characteristics shape pedagogical activity

The trainers state specific character traits that are fundamental to their activity, such as charisma, knowledge of human nature and talent. They consider their own biographical experiences to be of benefit to their work and compare the types of behaviour of the young people with their own in some cases. "I wasn't the best at school myself. This is why I understand them so well [...]. Because it's something I've experienced myself." (EI-LKL-AB-m-250). In seeking explanations, they draw upon know-how and subjective theories in their pedagogical activity which help them to be able to understand types of behaviour. This means that they bring their own biographical experiences to the pedagogical situation and transfer these to the young people.

Barriers in multi-professional cooperation

Analysis of the different practices of the four groups of professionals indicates barriers that exist between occupational cultures and the institutions. Occupational cultures are characterised by specific forms of perception and personality traits of those who work in the relevant occupation (cf. TERHART 1996, pp. 452 ff.) and are influenced by the societal level as well as being reproduced by individuals. For the respondents, the institutions represent systems which are largely closed and have their own culture and communication rules. This means that the trainers perceive school to be a separate milieu with a rigid set of rules.

Cooperation is also made harder by the unequal status of the partners. Companies hold the "defining power" and also decide on such matters as the success of others. A special needs teacher describes her dependence on the recruitment practice of the companies in the following terms. "It's difficult. Of course, we have an official remit. That is to place young people in training. [...] Our success is measured by the figures." (EI-F-SP-w-84). The fact that evaluation of the other professionals takes place on the basis of one's own values system also creates a block. This provides the other professional with little scope for entering into the cooperation. Hierarchisations and role allocations become clear, particularly in the case of training staff. Those who offer a practical occupational background enjoy the greatest degree of acceptance.

"The older vocational school teachers [...]. have a second educational pathway.

These are the best vocational school teachers." (EI-HH-AB-m-207). The special needs professionals receive most recognition when they offer the necessary support and can point to vocational education and training.

(Self) reflexivity as a significant dimension of pedagogical professionalism

Both the trainers and the other professionals interviewed confirmed that the three dimensions of knowledge, ability and reflection are all significant to them. Notwithstanding this, the acquisition of competences is predominantly associated with the gaining of (professional) knowledge. The question remains as to how personally related competences can be acquired. The trainers in particular display an understanding of pedagogy that tends to be instrumental. In their actions, they draw upon their know-how and subjective theories, which for them act as "individual convictions" (cf. MÜLLER/SULIMMA 2008, p. 1) and have the function of guiding their activities. Current studies confirm that these convictions exert a major influence on professional action (cf. MOSER et al. 2012) and that successful professionalisation primarily requires a linking of attitude, knowledge and action (cf. DÖBERT/WEISHAUPT 2013, p. 8). The findings of the BIBB research project confirm this, including with regard to multi-professional cooperation. Within the professionalisation process, it therefore seems necessary to acquire knowledge, develop ability, treat reflection as a cross-sectional dimension and to identify an attitude and mindset of the educational professionals as a fundamental dimension for pedagogical action.

The findings show that new forms of multi-professional cooperation need to be developed in order to enable cooperation to succeed. In this way, cooperation could be a professionalisation strategy (cf. BERKEMEYER et al. 2011, pp. 225 ff.) and create advanced training settings and areas of opportunity across professions and institution which facilitate a convergence of different perspectives (occupational cultures, institutional view etc.). Joint advanced and continuing training measures need to be designed which are adapted to company structures and are implemented in conjunction with cooperation partners (for example in the areas of career entry support or transitional coaching). Cooperation that is perceived to be constructive and supportive could mean that training staff become an even stronger stakeholder in structuring the transition and a fixed component of an educational chain.

Literature

ARNOLD, R.; GÓMEZ TUTOR, C.: Grundlinien einer Ermöglichungsdidaktik. Bildung ermöglichen - Vielfalt gestalten. [Basics of facilitation didactics. Facilitating education - shaping diversity.] Augsburg 2007

BERKEMEYER, N. et al.: Kooperation und Reflexion als Strategien der Professionalisierung in schulischen Netzwerken. [Cooperation and reflection as professionalisation strategies in school-based networks.] In: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik [Journal of Education], 57 (2011), pp. 225-247

BYLINSKI, U.: Gestaltung indvidueller Wege in den Beruf. Eine Herausforderung an die pädagogische Professionalität. [Structuring of individual pathways into work. A challenge to pedagogical professionalism.] Bielefeld 2014

DÖBERT, H.; WEISHAUPT, H.: Inklusive Bildung professionell gestalten. Situationsanalyse und Handlungsempfehlungen. [Shaping inclusive education in a professional manner. Situation analysis and recommendations.] Münster 2013

LEMPERT, W.: Berufliche Sozialisation: Persönlichkeitsentwicklung in der betrieblichen Ausbildung und Arbeit. [Vocational socialisation. Personality development in company-based training and work.] Hohengehren 2009

MAYRING, PH.: Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. [Qualitative content analysis. Basic principles and techniques.] Weinheim 2008

MOSER, V. et al.: Lehrer/innenbeliefs im Kontext sonder-/inklusionspädagogischer Förderung - Vorläufige Ergebnisse einer empirischen Studie. [Teacher beliefs within the context of special/inclusion pedagogical research - preliminary results of an empirical study.] In: Seitz, S. et al. (Eds.): Inklusiv gleich gerecht? Inklusion und Bildungsgerechtigkeit. [Inclusive and fair? Inclusion and educational fairness.] Kempten 2012, pp. 228-234

MÜLLER, S.; SULIMMA, M.: Überzeugungen zu Wissen und Lernen als Merkmal beruflicher Lehr-Lernprozesse. [Convictions on knowledge and learning as a characteristic of occupational teaching and learning processes.] In: Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik - online [Vocational and Business Education - online] bwp@ No. 14. 2008

TERHART, E.: Berufskultur und professionelles Handeln bei Lehrern. [Occupational culture and professional action by teachers.] In: Combe, A.; Helsper, W. (Eds.): Pädagogische Professionalität: Untersuchungen zum Typus pädagogischen Handelns. [Pedagogical professionalism. Investigations of the type of professional action.] Frankfurt a. M. 1996, pp. 448-471

WEINBERG, J.: Regionale Lernkulturen, intermediäre Tätigkeiten und Kompetenzentwicklung. [Regional learning cultures, intermediary activities and competence development.] In: Brödel, R. (Ed.): Weiterbildung als Netzwerk des Lernens. Differenzierung der Erwachsenenbildung. [Continuing training as a network of learning. Differentiation of adult education.] Bielefeld 2004, pp. 205-231

URSULA BYLINSKI

Research associate in the “Quality, Sustainability, Permeability” Division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 3/2014): Martin Stuart Kelsey, Global SprachTeam, Berlin

-

1

Cf. www.bibb.de/bildungspersonal-uebergang (status 26.03.14)