In-company training costs and organisation over the course of apprenticeship training

Felix Wenzelmann, Gudrun Schönfeld

Most companies providing apprenticeship training to young people initially incur costs, and view apprenticeship training primarily as an investment in the qualification of future skilled workers. The level of costs and returns shifts, however, over the course of apprenticeship training. Decisive factors in this, apart from rising training allowances, are the productivity of the apprentices and the organisation of apprenticeship training. The article outlines these developments with reference to the data from the BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey 2012/13 in occupations with different training durations.

Data basis of the Cost-Benefit Survey on Apprenticeship Training 2012/13

In the BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey 2012/13, human resources and apprenticeship training managers in 3,032 training companies from all sectors and company size-classes were questioned in personal interviews. A survey of 913 non-training companies was integrated. The total population consists of all establishments in Germany. In the sample, which was drawn from the Establishment File (the company statistics segment of the Federal Employment Agency’s employment statistics), training companies were significantly overrepresented. The results of the survey were extrapolated for the total population of companies using a weighting procedure and are therefore representative for Germany (cf. at length JANSEN et al. 2015).

Costs of apprenticeship training in occupations with different training durations

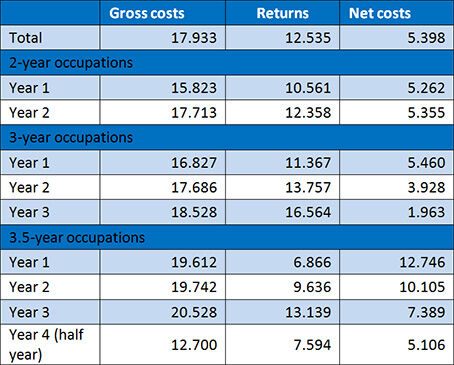

Gross costs – which consist of the personnel costs of apprentices and trainers, premises and non-personnel costs, and other costs – increase mainly because of the incremental rises in training allowances over the course of apprenticeship training (cf. Table 1). On average, gross costs are highest for the three-and-a-half year occupations because the companies’ investments in premises and non-personnel costs, in particular, are higher than for occupations with training of shorter duration.1 Among other factors, this correlates with the frequent use of, and expense of maintaining, a training workshop. Thus, in the two and three-year occupations, only eleven per cent of apprentices undergo part of their instruction in a training workshop as opposed to 44 per cent in the three-and-a-half year occupations. The returns from the productive contributions of apprentices also rise year on year over the course of apprenticeship training. In the two-year occupations, the increase from year one to year two of initial vocational training amounts to 17 per cent; in the three-year occupations it is greater still, rising by around 20 per cent from year one to year two and the same again from year two to year three (a rise of almost 46 % overall). In occupations requiring a three-and-a-half year duration of training, the returns in the first year are comparatively low, at EUR 6,866 and distinctly lower than in occupations requiring a shorter length of training. But here, too, considerable increases can be recorded. In the third year they already amount to EUR 13,139 and in the fourth year (which is just a half-year) EUR 7,594. Net costs (gross costs minus returns) in the two-year occupations are almost equally high in both years of the training, at around EUR 5,300. In the three and the three-and-a-half year occupations, they drop from year to year; in year four of the three-and-a-half year occupations (which is just a half-year), however, a rise can be observed once again. Overall net costs are the highest by far in these occupations.

Organisation of apprenticeship training: training periods in the company and at other learning venues

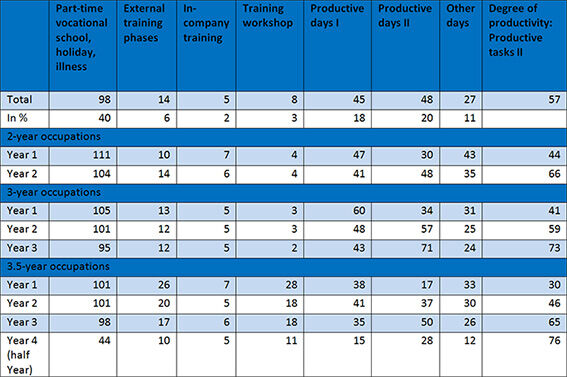

How do the year-on-year returns from training come to vary depending on the duration of training? Light can be shed on this question by differentiating according to training periods that young people spend in the company or at other learning venues (cf. Table 2). Accordingly, apprentices are absent from the workplace for part-time vocational school, holidays or due to illness for 40 per cent of the training period. The company has little influence over these periods of absence. Over 55 per cent of apprentices take part in external phases of vocational training, e. g. in inter-company vocational training centres, in chamber-run establishments or in other companies. On overall average, these account for 14 days. Within the company, in-company teaching is organised on five days of the year, in which around half of apprentices take part. Predominantly, vocational training in the training workshop is also one of the learning phases and accounts for around eight days a year. One in five apprentices is trained in this setting, and for these young people the number of days spent in the training workshop is higher. Apprentices spend around half of their training period, amounting to 120 days, in the workplace. This is where their work contributes to the production of goods and services. On 45 days they execute simple work tasks (productive days I) which can also be carried out by un-skilled and semi-skilled workers, and skilled work tasks on 48 days (productive days II). 27 days are allocated to instruction, practice, self-study periods and other periods.

During the first year of apprenticeship training in the three-and-a half year occupations, apprentices spend over one-fifth of their total time, or 26 and 28 days, in these two learning venues. Taking a look at the productive days, the skilled work task element of these increases considerably between the first and the last year of apprenticeship training, irrespective of the duration of training: from 30 to 48 days in the two-year occupations, from 34 to 71 days in the three-year occupations. In the three-and-a-half year occupations there is an increase from 17 days in the first year to 50 days in the third year and to 28 days in the fourth year (which is just a half-year). In parallel to the heavier work commitment, the degree of apprenticeship productivity in comparison to that of an average skilled worker in the company rises from 44 per cent (41 %; 30 % respectively) in year one to 66 per cent (73 %; 76 % respectively) in the final year. In other words, not only are the young people working more at skilled worker level but, at the same time, their work is of greater benefit to the company.

Apprentices in occupations of different training durations require different learning and practice periods. This has an influence on the level of returns and hence on the net costs of apprenticeship training. The periods of learning and practice are highest in three-and-a-half year occupations and lowest in three-year occupations. Since less time is available to deploy apprentices productively, the returns are lower in three-and-a-half year occupations than in occupations with shorter training durations, while the net costs are higher. Apprentices in two-year occupations are somewhere in between the figures for three and three-and-a-half year occupations. In whichever is the last year of their apprenticeship training, the apprentices in all occupational groups studied here attain a comparable degree of productivity in skilled work tasks. The upshot is that, for all occupations, the respective durations and organisation of training ensure that, on average, all those who attain an occupational qualification are approximately equally well prepared to work in their respective skilled occupations.

-

1

The duration of apprenticeship prescribed for the occupations depends upon the time deemed to be necessary to practise the occupational skills to the point of secure mastery in the work process. Thus, a majority of technical occupations (e. g. Industrial Mechanic) require three-and-a-half years of training because of their greater complexity. Two-year vocational qualifications (e. g. Sales Assistant), on the other hand, are more practice-oriented and impose less exacting requirements.

Literature

JANSEN, A. et al.: Ausbildung in Deutschland weiterhin investitionsorientiert – Ergebnisse der BIBB-Kosten-Nutzen-Erhebung 2012/13

BIBB-REPORT 1/2015 – URL: www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/show/id/7558 (retrieved 18.06.2015)

BIBB-REPORT 1/2015: BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey 2012/13 – URL: www.bibb.de/en/25852.php (retrieved 18.06.2015)

FELIX WENZELMANN

Research associate in the “Costs, Benefits, Financing” division at BIBB

GUDRUN SCHÖNFELD

Assistant in the “Costs, Benefits, Financing” division at BIBB

Translation from the German original (published in BWP 3/2015): Deborah Shannon, Academic Text & Translation, Berlin